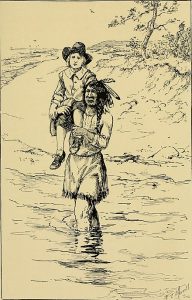

Tisquantum, also known as Squanto, has become a central figure in the story of the first Thanksgiving. In many versions, he was friendly to the Mayflower colonists soon after they arrived in what is now New England, taught them agricultural techniques that helped them survive the winter, and so he was invited to the first Thanksgiving feast.

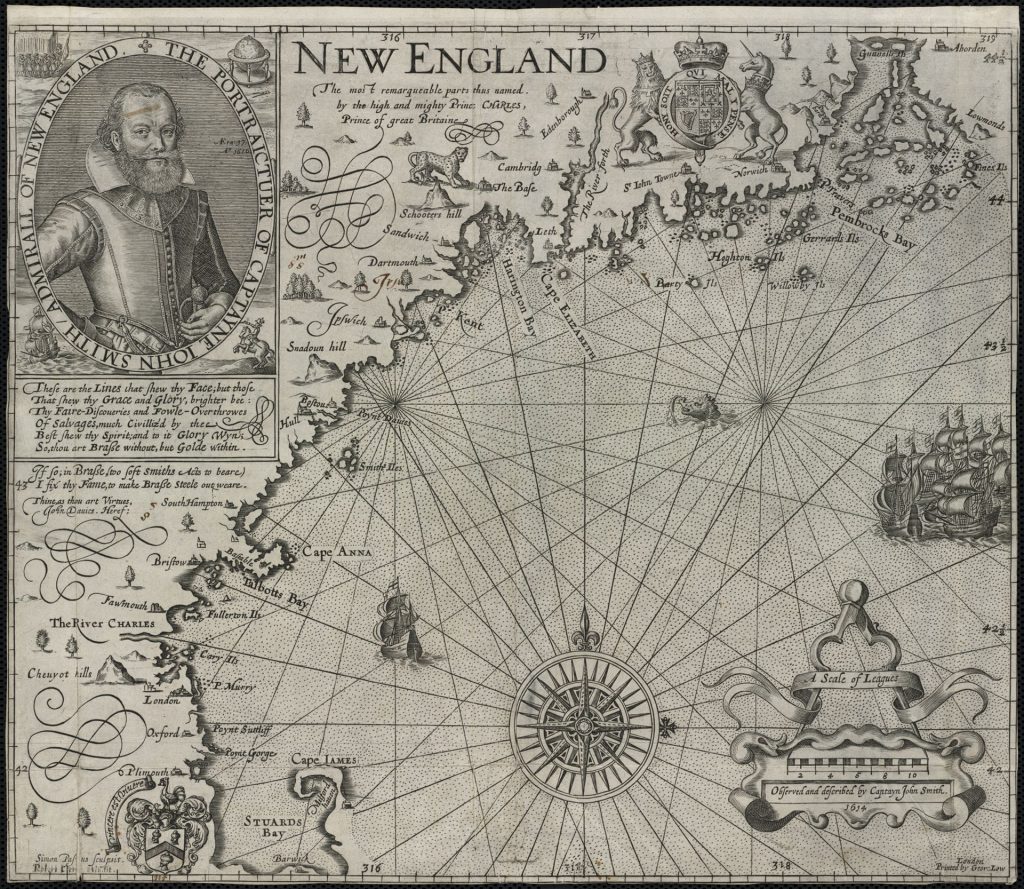

What this version of the story elides is how Tisquantum became so useful to the English colonists, specifically how he gained his ability to speak English. In 1614, he was captured by Thomas Hunt, an associate of John Smith, who sailed with him to Spain and there sold him into slavery. Eventually, he found his way to England and then Newfoundland before ending up in New England again as an interpreter for the English navigator, Thomas Derner. In 1620, he was again captured but this time by Wampanoag men, in whose service he met the colonists. While the historical narratives surrounding the Mayflower voyage and the first Thanksgiving have often placed Plymouth and the UK at the centre, with the focus on the movement of people flowing from Britain to what is currently the U.S., Tisquantum’s story illustrates how the reality was much more complicated than that.

As our research at Beyond the Spectacle has shown, British and Indigenous North American histories are entangled and they have been so since much earlier than the usual Mayflower narrative suggests. Indigenous peoples have been travelling to Britain since at least the early 1500s, as captives and as political emissaries. In 1502, three men from what is currently Newfoundland were presented to King Henry VIII, while in 1577, three Inuit captives (a man named Kalicho, a woman named Arnaq, and a baby called Nutaaq) were captured in what is now Baffin Island, Nunavut, and brought to Bristol, where they died. In the mid-1580s, visitors began arriving from the Algonquian homelands on the eastern coast of what is currently the United States, including Manteo and Wanchese, who helped the English mathematician and astronomer Thomas Harriot learn their language during their stay in Britain. In all, around 35 Indigenous North Americans visited and lived in Britain before 1615.[1]A year later, one of the most famous Indigenous visitors to Britain, Matoaka (more commonly known as Pocahontas) was feted by London society before her death at Gravesend in March 1617. As Coll Thrush has argued, the knowledge and physical presence of these Indigenous peoples, “whether as captives or emissaries,” transformed Britain and its colonial project.[2]For the Indigenous peoples of New England, however, the consequences were more complex. As Christine DeLucia has noted, becoming “deeply entangled in the Atlantic World” could be “enriching or broadening” but it could also cause incredible damage, especially with the captives who never returned, “leaving behind critical gaps in community demography.”[3]

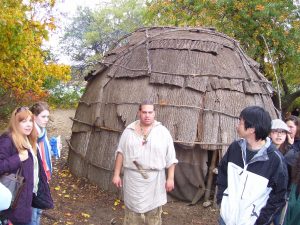

So why does this matter? The Wampanoag nation have faced very real consequences to their marginalization in the larger story of the Mayflower and the founding of the Plymouth colony, particularly in their continuing fight to maintain control of their land, as many Americans believe they no longer exist. In March of this year, for example, the Department of the Interior ordered that the Mashpee Wampanoag reservation be disestablished, forcing the Wampanoag to initiate legal proceedings to prevent it (see link below for more information). Since the 1970s, Wampanoag people along with many others have gathered at Cole’s Hill in Plymouth, Massachusetts, on the fourth Thursday of November. There, they observe a National Day of Mourning beside a statue of Massassoit, the Wampanoag leader who welcomed the Mayflower settlers and attempted to live peacefully with them until his death in 1661. This is just one example of the ways in which the Wampanoag have been taking back control of their narrative, displacing generations of American myth making. It is only right, then, that they take over the story here. Please follow these links to several Wampanoag-led perspectives on the encounter with the English and a reminder, as the third of these links notes, that in spite of the catastrophic events unleashed over the following 400 years, the Wampanoag, along with many hundreds of Native nations across the United States, have endured:

Plymouth 400 – Our Story: https://www.plymouth400inc.org/our-story-exhibit-wampanoag-history/

“Our” Story: 400 Years of Wampanoag History: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL_SEJpPfEF9wgV3few2-8rwKHHXmFJ8uu

Listening to Wampanoag Voices: Beyond 1620: https://www.peabody.harvard.edu/listening-to-wampanoag-voices-beyond-1620#:~:text=%22In%202020%2C%20the%20year%20that,the%20foothold%20of%20New%20England

Stand with Mashpee Wampanoag against federal attempts to take their land: https://mashpeewampanoagtribe-nsn.gov/standwithmashpee

Kate Rennard, Beyond the Spectacle Research Assistant

[1]See Alden T. Vaughan, “American Indians in England (act. c. 1500-1615),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 25 November, 2020; Coll Thrush, Indigenous London: Native Travellers at the Heart of Empire(New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 44.

[3]Christine DeLucia, Memory Lands: King Philip’s War and the Place of Violence in the Northeast (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), 294.