BSIS students recently had the opportunity to take part in an EU crisis communications brainstorming session, attended by European Commission communication specialists, world-class researchers and experienced government communication professionals.

The session was led by Tom Moylan from the Office of the Director-General for Communication, social media analyst, digital strategist, and former speechwriter.

The goal was to bring together the worlds of research and practice to develop new, evidence-based communication approaches.

Tom Moylan has prepared the below reflections, incorporating the names and suggestions from BSIS students, and shared it with the staff of the Directorate-General for Communication in the European Commission.

On 18 May, a group of students, researchers and communication experts came together to discuss EU communication and see what fresh ideas we could come up with. This is how it went down.

Principles in Crisis Communication

To begin, we established some basic principles of crisis communication by analysing a series of statements by different actors (for a breakdown of the process, check out this blog). Among the things that are important to consider in a crisis are timing, symbols and production processes.

One of the more interesting aspects of this discussion was around roles and expectations in a crisis. From the Queen of England to the European Commission, everyone has a role and expectations that come attached. A crisis communicator should have a good understanding of their organisation’s role in order to effectively respond to a crisis. A few questions emerged to help guide communicators in understanding their role:

- What is our role in the crisis?

- What do people expect of us?

- What can we actually do to help?

- What traditions or processes will influence your response?

- What questions might people ask about our involvement?

- What level of emotion is appropriate to express?

What bubbled up at large is that your response to a crisis should in no small part be shaped by the expectations around your organisation. In this vein, crises can be opportunities to reshape expectations and build trust. The flip side of that coin is that the traditions or processes that define your organisation (or that you might understand to define it) are not always useful in a crisis – and indeed, can sometimes be obstructive.

What makes Corona different?

Every crisis is different – so beyond understanding your place in a crisis and the mechanics you will use to respond, it is important to understand the unique characteristics of the crisis you are in. The students came out with the following insights on coronavirus:

- It affects people’s freedom in a very practical way – and leads to people asking fundamental questions about the balance between freedom and safety.

- It is a slow burner – it did not arrive suddenly, nor will it depart quickly either. This makes it an outlier among crises, which are typically short and catch organisations by surprise.

- While the example we had discussed before (Princess Diana’s death) had sadness in common with the coronavirus, the real mark of corona is an encompassing and collective anxiety.

- It is a striking illustration of how policy and politics can impact people’s daily lives – from simple routines to their very survival.

- No one is responsible for the crisis at large, which means that the primary focus is on response.

- Whether themselves or their families, everyone is vulnerable in the face of corona.

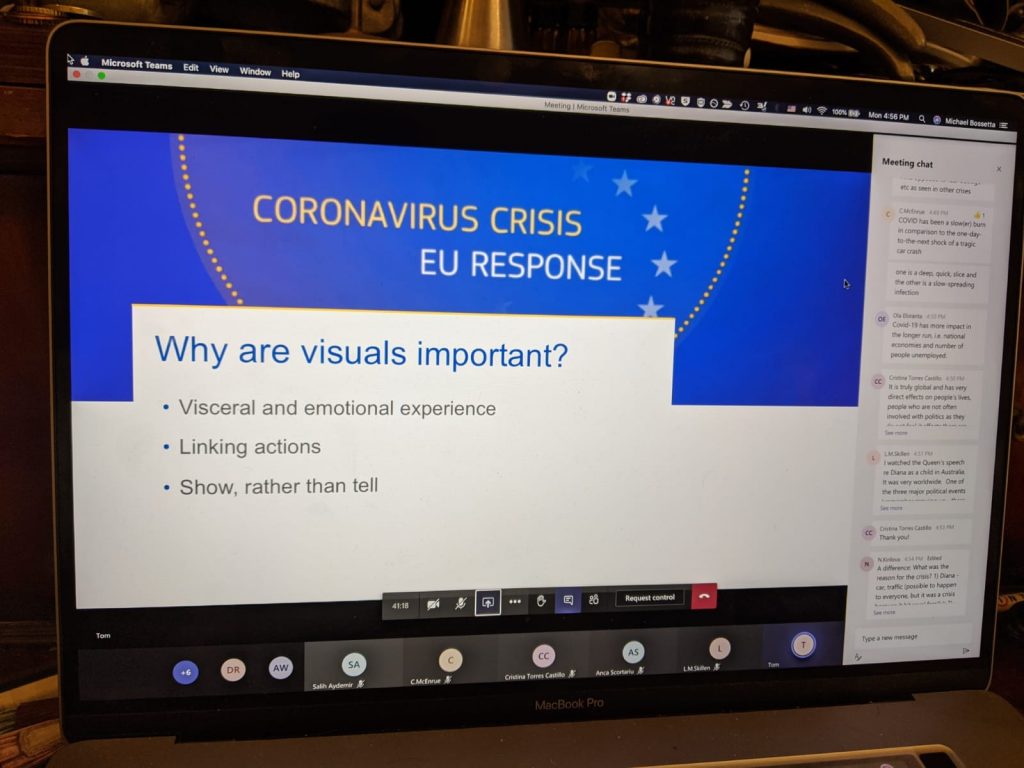

Zoom-in: Visualising Crisis Response

For the final part of the exercise we “zoomed-in” on two aspects of coronavirus crisis communication response. This was used as a springboard into a broader, more open discussion. The two examples presented were the visual communication response by the Commission in the coronavirus crisis and the Global Response – one being chosen as a sustained response and the other as a specific event.

The visual response is important. A crisis is a visceral and emotional experience, and the visual response was created with that in mind. The cool, calm visual identity knits together experiences and associations, while the focus on action (supplies being transported, acts of solidarity, etc.) shows the striking reality of EU action. All of this had to be balanced against the technical restraints of managing a rapidly changing message with a large team of multilingual and multicultural communicators across a wide geographical area.

Meanwhile, the Global Response was an online event hosted by President Von der Leyen where world leaders called in and pledged €7.4 billion towards the coronavirus response. The mix of striking visuals, technical execution and digital diplomacy were among a number of factors that made it successful.

Several interesting lines of conversation emerged in response to these examples, including reflections on the difficulties of getting Commission actions into local and national media, and opportunities available in overcoming this in going online and using social media.

Recommendations from Participants

Based on these discussions of roles, context and content, the participants came out with a series of recommendations for EU communicators:

- Recognise that people do not think of crises as accidents. They will hunt for a scapegoat and the EU needs to avoid becoming that scapegoat. A thorough discussion of both how that could happen and be avoided is key to the EU’s strategic thinking.

- Go live – whether it is the live with Commissioners, press conferences or online town halls, the Commission needs to embrace and expand live streaming further. This will only become more important as people become more used to the format during the current crisis.

- Cracking into local and regional actors is key – not just the media, but also civil society and local governments. More cooperation with local actors helps go around the national media’s crowded agenda and cut through the noise of other actors competing for attention.

- Youth should be a strong focus. Not only are they generally friendly towards the EU and open to its benefits, but it is a long-term investment in the EU’s future.

- The EU needs to enter mainstream culture somehow – whether that is an Obama-like rock star, a TV series or another piece of culture has an impact beyond the news messages.

- A European information stream is key – whether that is developing social media further or conceiving of something new, there is a need to think outside the box.

- There has been a move towards less formal language in the EU, but the transition is patchy and far from complete. This trend is encouraged and should be built on.

- Build on the digital diplomacy approach – national governments have well established social media channels, to which we should try to share access. For example, the President has chats, debates and interviews with other leaders live online.

- Universities and think tanks are potent networks to go through and have the advantage of established images as non-politicised actors. They could be an opportunity as networks to spread messages, both formally and informally.

Thanks to:

- Visual Communication and Audiovisual Teams of the European Commission.

- Special guest brainstormers Anca Scortariu, Michael Bossetta, Dominique Roch and Alex White.

- Laura May Skillen for organising and contributing to the event.

- Students who contributed: Ana Londoño Botero, Claire McEnrue, Cristina Torres Castillo, Neli Kirlova, Ola Eloranta, Salih Aydemir, Willem Van Ransbeeck.