26/04/2016

The Gulbenkian Cinema will also be showing Beckett’s Film, starring Buster Keaton, and Ross Lipman’s Notfilm over the weekend following the SBWL Conference. Click on this link to book your seats.

23/4/2016

Selin Siral has very generously designed for us the SBWL Poster, and she will be joining us at the conference next month!

9/2/2016

Fun fact: In 1961, Samuel Beckett married Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil in Folkestone, 50 mins from the University of Kent, and spent a couple of weeks in the south of England, traveling through Canterbury, Rye, Hastings, and other cities and villages around.

Maybe this calls for some literary tourism around the conference dates?

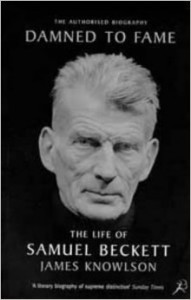

Here are a few pages out of James Knowlson’s biography Damned to Fame, if you might be interested:

Once he had made his decision to marry Suzanne, their main aim was to keep the projected ‘nuptials’ from becoming public. This meant telling as few of their friends as they could and getting married in as much secrecy and with as much haste as possible. He had discussed his decision to marry with the Haydens and the Arikhas in Paris and with Tom MacGreevy, Con Leventhal and Alan Schneider while they were visiting Paris. Now, he talked to the publisher of his prose writings in England, John Calder, as to how the plan could best be put into operation. In order to establish Suzanne’s inheritance, since he was of Irish nationality, Beckett needed to be married in England, not France. Joyce did the same for the same reason with Nora in July 1931, although, because Joyce’s wedding took place in London, he did not entirely succeed in avoiding publicity. Getting married was easier in England than in France anyway. It was Calder’s suggestion that Beckett should get married in the Registry Office of a quiet, seaside town on the south coast of England. Folkestone fitted the bill admirably, since it was close to France and would allow them to return to Paris immediately after the wedding.

A few days after his return from Amsterdam, Beckett set off in what he called his ‘two nags’ (or Deux Chevaux Citroen) for Le Touquet. There he made the short ‘hop’ across the Channel, using the Silver City Airways car ferry service to Ferryfield airport at Lydd in Kent, only about fifteen miles across the reclaimed Romney marshland from Folkestone. He was obliged to be in residence in Folkestone for a minimum period of two weeks to allow him to be married in the Registry Office there. So he checked into the seafront Hotel Bristol, which was demolished later in the 1960s, at Nos. 3 and 4 on the high cliff road called The Leas, opposite the unusual 1885 Water Balance Lift. A reservation had been made for him by John Calder.

The Bristol, a smallish hotel of only twenty-two rooms which cost from seven to nine guineas a week with full board, was chosen rather than a larger, better-known hotel like the Pavilion, the Grand or the Metropole so as to lessen his chances of being recognised. The hotel was not particularly comfortable but it had a fully licensed bar. In registering, Beckett used his middle name, ‘Barclay’, to preserve his anonymity. He was scared that, if a local journalist were to get wind of his presence there and alert the national newspapers, a secret wedding would become impossible. Suzanne wanted no friends present as witnesses either. When he wrote to those other than the very small circle of intimates already in the know, he used innocuous phrases like ‘having a bit of rest here in Folkestone and environs’. He signed a postcard to Avigdor Arikha in Paris simply ‘S’, and wrote ‘Sang coule plus calme dans la ville de Harvey’ (Blood flows more calmly in the town of Harvey), for Folkestone was the birthplace of William Harvey, who discovered the circulation of the blood.

The day after his arrival, Beckett called on the Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages for the sub-district of Folkestone, D. A. P. Cullen, in the offices at 29 Bouverie Square. The Registrar was sympathetic and helpful and told Beckett that, as long as he retained his room at the Hotel Bristol, he could travel around the region as much as he liked. He avoided London like the plague. But he spent a few days with his cousin, Sheila Page, in Surrey. Being away on his own reminded him of the literary and artistic pilgrimages that he used to make in the mid 1930s. He visited Rye in East Sussex, taking a genteel afternoon tea in the half-timbered Ancient Vicarage where, traditionally, the dramatist, John Fletcher, is said to have been born in 1579.

Beckett also drove on to Brighton, where he spent a pleasant evening with the book collector and dealer, Jake Schwartz, staying overnight at the former dentist’s house. In a Brighton bookshop, he bought George Birkbeck Hill’s six-volume edition of Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson (1887) that he had worked on in the 1930s and had ‘been looking for in vain for years’. He did not breathe a word to Schwartz about his forthcoming marriage: to explain his presence in England, he simply said that he was resting after his recent trip to Bielefeld. This was to be the last occasion on which he felt trust for the dentist whom he later used to call ‘The Great Extractor’, for he soon learned through another dealer, Henry Wenning, who, in future dealings, shared the profits on sales far more generously with Beckett, that Schwartz had been paying him only a small percentage of the true value of his manuscripts.

He took the car for numerous drives to Winchelsea and Canterbury, as well as Rye, Hastings and Brighton and spotted on his map of the area, the name of Borough Green which he slipped into the second manuscript version of Happy Days – the nearby larger town of Sevenoaks was an alternative suggestion added by hand to typescript two – and discovered the delightful names of Ash and Snodland in Kent which he used a year later in Play.

Mostly though, the dank days limped leadenly by, as he hung around the town ‘trying to be invisible’. He found the food in the hotel execrable with ‘marvellous Dover sole reduced to consistency of paste but sat on most nights in quiet country pubs relishing pints of draught Guinness. In the hotel, he tinkered with the manuscript of Happy Days, gazing out at the sea and the sky and the tips of a few fir trees rising from the wooded cliff. He also dealt with a huge pile of accumulated mail. But it was hard to concentrate and, feeling as he put it ‘half chlorophormed’, he regularly gave up and went to bed at half past nine.

After a few days, something happened that put the entire wedding in doubt. Beckett received a message that his cousin, John Beckett, had been badly injured in a serious car accident in Ireland. He thought he would be needed in Dublin and spoke of travelling over to be with John’s mother and sister. But, when he called his aunt Peggy, it was to learn that, although John, driving back home in a Mini from an evening playing Haydn string quartets with friends, had hit a wall about 4 a. m. in Little Bray breaking his arms and badly damaging his hip and his ankle, his vital organs were undamaged and his life was not in danger. Peggy assured Beckett that nothing could be gained by interrupting his stay and that a visit later on in the year would be far more welcome, since John was expected to have to remain in hospital for a minimum of three months, followed by a further three months of convalescence. In the end, John was hospitalised for a full five months. Beckett had been prepared to abandon the wedding and start all over again. But, reassured by what he heard, he decided to stay put and to telephone John’s future wife, Vera, and Aunt Peggy regularly in Ireland.

Suzanne did not need to reside in England to be married there. So she came over only three days before the wedding. Early on Saturday morning, 25 March 1961, the simple ceremony was conducted by Charles G. Mayled, the superintendent Registrar, and registered by D. A. P. Cullen. So, in a marriage recorded as No. 66, a fifty-four-year-old bachelor, Samuel Barclay Beckett, writer, was finally married to a sixty-one-year-old spinster, Suzanne Georgette Anna Deschevaux-Dumesnil, before two witnesses, E. Pugsley and J. Bond, who were either plucked off the street or worked in the Registrar’s Office. Two days later, back in Paris again, Beckett wrote to Con Leventhal:

“It was good of you to wire and telephone. I wish you could have been with me, but Suzanne was determined on nobody. All went without a hitch, in absolute quiet. We returned to France the same morning and arrived in Paris Saturday in time for dinner after an easy drive from Le Touquet. Thank God it’s done at last.”

There had been two minor scares about the secret getting out: the first when a case of champagne arrived at the hotel, ordered by Barney Rosset from New York, and the second when, early on the morning of the wedding, a local reporter, a ‘stringer’ for the Daily Express, telephoned John Calder at home to ask him whether a man getting married in Folkestone that day was his author, Samuel Beckett. Thinking quickly, Calder said that this could not possibly be true since he had just received a postcard from the writer, Samuel Beckett, who was on holiday in North Africa.

James Knowlson, Damned To Fame, 1996/97, Bloomsbury: London. Pages 481 to 484.