Meta Warrick Fuller Maquette for Ethiopia Awakening. Image courtesy of the Danforth Art Museum at Framingham State University.

An extraordinary poem and essay extract by third year Art History student Jane Ditcher. In her poem, Jane used the titles of Meta Warrick Fuller’s sculptures as inspiration. The poem’s shape and title recall Fuller’s famous sculpture Ethiopia Awakening.

Extract from the essay: Underexplored women artists

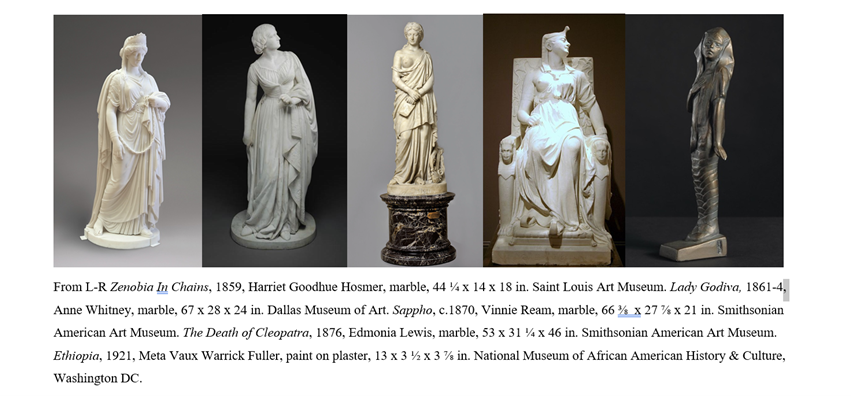

Fuller’s Ethiopia Awakening (1921), was commissioned by W.E.B. Du Bois and James Weldon Johnson (1871-1938), activist and Du Bois’ NAACP colleague,[1] for America’s Making Exposition of 1921.[2] A copy of Ethiopia now welcomes visitors to the Visual Arts Gallery in the National Museum of African American History and Culture. The curator Tuliza Fleming says, “for me, the 20th century begins with that piece,”[3] offering a crucial insight into how significant this work was regarding the uplift of the African American race at the time it was commissioned, and the legacy it honoured. Here we see a pseudo-Egyptian black woman[4] wearing a Nemes, the headcloth of Egyptian pharaohs, as a mummy unbinding herself from her bondage. Her head is turned to the side which thrusts her gaze out in a meaningful ‘I am going forward, not backwards,’ and the hand holding the end of her shroud is positioned at her heart, as if in loyal solidarity. The other hand turns out in a feminine, pose, discreetly guiding the direction of thought.

Ethiopia is much smaller, at just one foot (30 cms) high, than some of its neoclassical counterparts like Zenobia in Chains (1859), Lady Godiva (1860-3), Sappho (1870), and Death of Cleopatra (1876), which are all over a metre high. This inform us women had the physical strength to create large-scale works, and along with Fuller’s Ethiopia are examples of these women decrying intersectional discrimination and inequality by using sculpture to uplift their gender and race. Together these sculptures “offered an alternative model to the traditional captivity-narrative protagonist, upending the feminine colonial stereotype of the passive languishing victim.”[5] While offering us representations of femininity with flowing gowns, coiffured hair, womanly poses, a displayed breast, or tapered waist, the unrequited gazes neither offer availability nor invite the viewer in. The women’s deportment and in some their gaze, insinuate a defiant insouciance of independence, analogous of the women who negotiated the masculinity of sculptural spaces, to overcome conformity and create these works. “The concept of artist as male genius and the stereotype of femininity as inherently incapable of genius,”[6] was being literally and figuratively heartily nullified by these underexplored women sculptors.

[1] Judith N. Kerr, “God-given work : the life and times of sculptor Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, 1877-1968,” (Unpublished PhD, Doctoral Dissertation, University of Massachusetts, 1986), 259.

[2] Renée Ater, Remaking Race and History The Sculpture of Meta Warrick Fuller, (California: University of California Press, 2011), 2.

[3] “Black History takes its place on Washington’s Mall,” The Art Newspaper, accessed May 1, 2023..

[4] Renée Ater, “Making History: Meta Warrick Fuller’s ‘Ethiopia,’” American Art 17, no. 3 (2003): 13, accessed April 29 2023, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1215807.

[5] Melissa Dabakis, A Sisterhood of Sculptors American Artists in Nineteenth-century Rome, (Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2014), 134.

[6] Rozsika Parker & Griselda Pollock, Old Mistresses Women, Art and Ideology, (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 1981, 121.