Salman Toor’s intersectional identities, as a gay man of colour working in the west, blur any positioning of him in a west/rest binary.

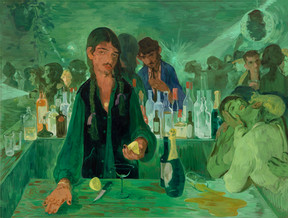

Salman Toor, The Bar on East 13th Street (2019)

Salman Toor (b. 1983 Lahore, Pakistan) uses the queer, non-white figure and hybridised visual references to communicate the realities of identity and sexual expression in both the country in which he was born and where he works. The characters in his paintings are usually situated in familiar, safe, everyday surroundings, often interacting confidently: queer and comfortable in their brown, desirable bodies.

Toor is heavily influenced by European art history and the paintings of the ‘old masters’ (Trasi 2020). His paintings refer to the canon in both technique (his brushwork and use of oil paints) and subject such that one might argue he makes known his knowledge of the canon in order to gain a position in it for himself. For example, The Bar on East 13th Street (2019) references Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882), recasting the bartender as a queer character who, unlike their counterpart in the Manet, exudes relaxed assurance and sexual agency, refusing to be pinned down in terms of gender, sexuality, or race (Vali 2020). Such agency is perhaps also evident in Toor’s character holding a piece of fruit, cut and ready for use, which, as a sensual metaphor, contrasts to the fruit in Manet’s painting which sits in a bowl ready for the taking by a client. The green hue and sense of uncontrollability (e.g., in the spilled drink on the bar) in Toor’s painting evoke a sense of chaotic calm and an assured serenity, a homeliness encapsulated also in the ‘houseplant’ on the top left; this is in stark contrast to Manet’s bartender who is very much at work. As such, Toor succeeds in critiquing – using its very canon – the art history which has long excluded, or at least misrepresented, the brown, queer subject. His subversive and ironic use of the canon also, paradoxically, means he avoids being forced to play its game, as queer artists have had to in the past (Moffitt 2015).

Toor is an artist who fully inhabits a space not in a binary hierarchy but in a plural, diverse world of both power and marginalisation. As Enwezor (2003, p. 58) writes of contemporary art, the mixing of cultures in a multicentric world involves such a ‘constant tessellation of the outside and inside’. Toor’s paintings are all of imagined characters and scenes, yet he presents this ‘inside’ experience with a knowing awareness of the ‘outside’, seamlessly amalgamating references to both the contemporary world and the western (orientalist) canon. He ingests and inverts western artistic techniques and subjects to further the struggle of those marginalised by a west/rest binary (Shohat & Stam 1998 and Trasi 2020). Toor’s work, therefore, lies both in between and outside art histories dualistic traditions, ‘operating between academic painting and illustration, and between fiction and autobiography’ (ibid.). Here, the same power of the artist which in the past has disempowered the non-western nude subject is used to empower the subject, as Toor is able to imagine and represent his own experience, rather than have someone else do so for him (Said 1978 and Nochlin 1991). Furthermore, in being aware of how the viewer will see his characters in light of their social positions – as queer, brown, hairy men – Toor explores and subverts the expectations of the white, male, heterosexual gaze (Trasi 2020). The marked difference in Toor’s nude portraits when compared to traditional western nudes, means the subjects are not essentialised as simply non-western, but depict complex individuals who could just as easily be located in Lahore as in New York City (Diament, Toor & Tovey 2020).

An extract from Joshua Stevens’ work undertaken on the BA module: Dialogues: Global Perspectives on Art History, 2021.

Diament, R., Toor, S. and Tovey, R. (2020) Salman Toor (NYC Special Episode) [Podcast]. 13 November. Available at: https://play.acast.com/s/talkart/salmantoor-nycspecialepisode- (Accessed: 18 April 2021).

Enwezor, O. (2003) ‘The postcolonial constellation: contemporary art in a state of permanent transition’, Research in African Literatures, 34(4), pp. 57-82.

Moffitt, E. (2015) ‘Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s ecstatic antibodies’, Transition, 118, pp. 74-86.

Nochlin, L. (1991) ‘The Imaginary Orient’, in The politics of vision: essays on nineteenth-century art and society. London: Thames and Hudson, pp. 33-59.

Shohat, E. and Stam, R (1998) ‘Narrativizing Visual Culture: Towards a Polycentric Aesthetics’, in Mirzoeff, N (ed) The Visual Culture Reader. London: Routledge, pp. 27-49.

Trasi, A. (2020) The self as cipher: Salman Toor’s narrative paintings. Available at: https://whitney.org/essays/salman-toor-self-as-cipher (Accessed: 15 April 2021).

Vali, M. (2020) Salman Toor’s “How Will I Know”. Available at: https://www.art-agenda.com/features/364886/salman-toor-s-how-will-i-know (Accessed 18 April 2021).