Enquiry into the nature of a chance machine

by Joshua Carter

A sonnet written by a machine

will be better appreciated by another machine.

Alan Turing

And there you are—an infinitely original author of charming sensibility,

even though unappreciated by the vulgar herd.

Tristan Tzara

As part of my creative portfolio I wrote a short programme that automated the creation of a Dada poem, as described by Tristan Tzara. I don’t know if it can be considered “surrealist”, however if it isn’t, I think that a brief autopsy of this project will help explore the boundaries of surrealism, and whether it will remain a viable philosophy as we move into the future.

Tzara’s original formula can be summarised as the subjection of a pre-written text to the laws of chance, stripping it of its original meaning, and giving it the potential for new ones. This is the core of what I wanted to recreate with my program.

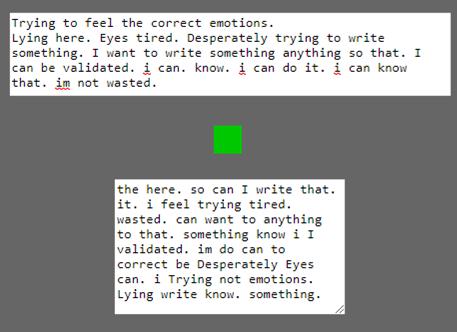

Here is an example of how it works:

I’ve chosen an old diary entry from the 2nd February 2017, and faithfully copied it into the top textbox. It was clearly something meaningful to me at the time, although now I can’t quite remember the context; I figured that if there is any inherent meaning baked into these words, the laws of chance might bring them out again.

The text has been jumbled and output into the bottom textbox: my “poem”.

The new text has obtained a new sense of pacing and mood from the irregularly placed periods, while the erratic capitalisation implies objects and nouns imply new ambiguous significance. Besides the nonsense grammar that a Dadaist would revel in, there are also some juxtapositions that allow the reader’s unconscious to make new connections, and lots more potential for use with other texts.

That being said, I think there is something missing compared to Tzara’s formulation. Pulling the words out of a hat lends Tzara’s process the connotation of magic and creates a mysterious tension that is completely lost with my program that works at the push of a button. The instant randomisation, the fact you can no longer touch the words, and the possibility of infinite repetition all give the program a distasteful and inhuman quality. This is not Breton’s objective chance, guided by the unconscious association of the mind, but real randomness rooted in mathematics and logic.

The mathematical objects of the Poincaré Institute were a source of inspiration for many surrealists including Max Ernst and Man Ray. What appealed to them were the organic and anthropomorphic forms that had derived from algebraic formulas, representing the move away from logic and towards the subjective realm of the unconscious.

Ray captured the appeal of the objects when he said that “the formulas accompanying them meant nothing to me but the forms themselves were as varied and authentic as any in nature” (Hoving). What interests me however, is how he misses the fact that all of the forms of nature are built on mathematics.

The machinations of the city were a constant source of daydreams and mythologies for the surrealists who couldn’t conceive of the massive web of connections that sprawled out in front of them. This meant that when a chance encounter presented a glimpse of order, it was intensely profound.

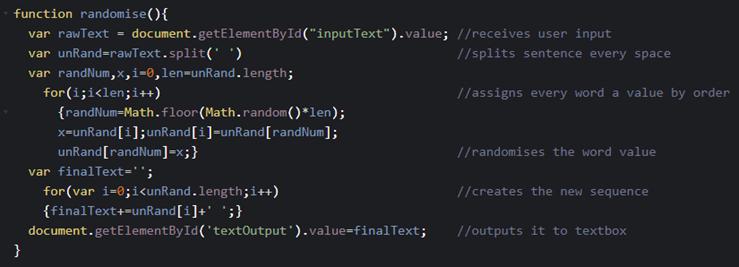

The randomness that produces my poem, however, can be presented in full:

If the schematics of our universe were presented to us like this, would the chance encounter lose its magic? What about the creation of art?

With a few lines of code you can create an infinite number of original poems, and as technology and AI advance they will continue to problematise the surrealist’s anthropocentric privileging of the unconscious, reproducing without fanfare the accomplishments of the human imagination.

As the schematics underlying poetry and painting continue to be demystified, we will have a choice to make: either to pay attention, or to close our eyes and preserve the magic.