The narrative of the new Ubisoft video game Far Cry 5 speaks to what seems a powerful political moment, of an American nation literally at war with itself.

In an article published recently on The Conversation, The Centre for America’s Dr John Wills explores how the new video game Far Cry 5 speaks to today’s divided America:

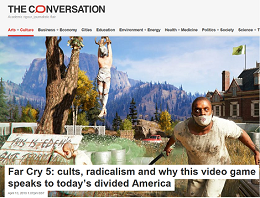

You are a rookie law enforcement officer, on board a helicopter heading into the main compound of Project at Eden’s Gate, a religious cult operating across a huge stretch of Montana. A towering statue of the militia’s leader, Joseph Seed, rises into the sky. With a warrant for the arrest of Seed, you navigate a warren of buildings patrolled by aggressive white men and their snapping dogs, before entering a white-boarded church. A haunting rendition of Amazing Grace plays in the background as you meet Seed for the first time, in an almost dream-like sequence. From there, you are transported to an intense face-off between militia extremists and federal officials.

This is what you would experience on playing the new Ubisoft video game Far Cry 5 (2018). Its story speaks to what seems a powerful political moment, of an American nation literally at war with itself.

While already a huge financial success (with reports of nearly five million copies sold in its first week of release), Ubisoft’s title has been widely criticised for its overt lack of political message. The Montreal-based company may have promoted its game as a serious take on religious and political radicalism, but so far journalists have labelled Far Cry 5 a title unwilling to squarely take aim at Trump’s America, or speak directly to matters of contemporary racism, endemic gun culture, or right-wing extremism. Instead, reviewers have called it “totally unconvincing” (PC Gamer), “a missed opportunity” (The Outline), and a game that ultimately “says pretty much nothing about” modern America (The Guardian).

Are we being too harsh on the game? After all, most entertainment companies hype their products. Equally, would a film or novel tackling religious cults be criticised for not engaging with the wider problems of Trump’s America? In my view, video games do not need to make blatant political statements to be considered art or satire, nor do they need strong messages to have impact. Ultimately, gamers make their own readings and experiences, without the need to be constantly “billboarded”. Click to continue reading this article on ‘The Conversation’.

Dr John Wills is Reader in American History and Culture at the University of Kent’s Centre for American Studies. He will be exhibiting his latest research on videogame representations of the United States at the British Academy Summer Showcase on 22-23 June 2018.