Prof. Peter Taylor-Gooby, WelfSOC project leader, looks at the winners and losers in George Osborne’s spending review

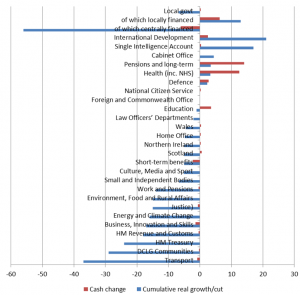

The UK Treasury’s Autumn Statement and Spending Review sets out the plans for state spending for the next five years, up to the next general election. This review was widely trailed as touch: the Chancellor demanded that all departments (except those protected: the NHS, International Development, schooling from 5 to 16 years and old age pensions) prepare plans for cuts of between 25 and 40 per cent, on top of the steady diet of austerity since 2010. In the event the review headlined much lower cuts than those anticipated and largely shielded the tax credits that top-up the wages of the very low paid. It also halted the downward trend in defence spending and gave £2bn extra to intelligence (or spying). The NHS received an extra £8bn over the period on condition that it achieved further ‘efficiency savings’ of £22bn (see the chart below). A new higher state pension will be introduced from next year, at a cost of some £5bn.

The most noteworthy cuts were to transport (37 per cent), the communities budget which deals with planning, housebuilding, support for troubled families, ethnic minorities and other issues (32%), the tax authorities (24%), business and innovation (18%), environment (16%) and work and pensions (14%) mainly in cuts to administration and short-term benefits. These cuts may not be obvious to most people in the short-term but spell real problems for infrastructure, climate change policy, innovation and the tax-raising essential to sustain spending.

The Chancellor made scant mention of the biggest cut of all, a 56% cut in what central government transfers to local councils.

How was the Chancellor able to avoid steep cuts for high-profile departments? First the independent Office of Budgetary Responsibility produced highly optimistic forecasts of growth, employment and inflation which underpin everything. The Chancellor was able to claim that he could impose fewer cuts than planned and still keep to his target of a current account surplus by 2020/21. These forecasts exceed those of independent forecasters from 2017/18 onwards (see HM Treasury, Forecasts for the UK Economy) so the Chancellor’s plans may rest on shaky ground.

Second, the future plans do not mention the continuing cuts in programmes like short term social security benefits (frozen for four years) or social housing (with housing associations, now the main providers, forced to sell off housing and major cuts to means-tested rent benefits). Why should they? They’re plans for the futures starting from now – but the cuts already in place will still affect those on low incomes.

Thirdly, the Chancellor made scant mention of the biggest cut of all, a 56% cut in what central government transfers to local councils for services like local roads, cultural provision, community care for frail adults and social work with vulnerable children. These services have already experienced a 28% cut since 2010.

The justification of this omission is that local government will be able to make up the shortfall by increasing charges, imposing new local taxes and selling off assets, such as land and housing. Some councils will – mainly those in the richer areas of the South and South-East and the more prosperous big cities, with buoyant local industries tax-payers affluent enough to pay more. In the areas with the greatest needs, mainly in the North, West and Midlands, it is not possible to raise the money because it simply isn’t there.

The UK spending plans follow some of the themes of recent years: continued austerity, continuing favouring of the old at the expense of the young, continuing concentration of government spending in the rich South-East and little attention to infrastructure investment or the research and innovation necessary for stable growth.

Main changes in the Spending Review, 2015-16 to 2019-2020 (click to enlarge)

Source: Spending Review and Autumn Statement 2015 Cm 9162 Table 1.5, 2.1 and 2.17

(Another version of this post has been published on The Conversation)