Additional material by Alison Sandford MacKenzie

On 25th September 1914, the Mayor of Tunbridge Wells, Charles Whitbourn Emson called a meeting of interested parties to discuss his proposal to open a Municipal Fund and set up a Borough Committee to help the refugees arriving in the town.

He wrote to the Belgian War Relief Committee in Folkestone:

Dear Sir –

I am pleased to inform you that arrangements have been made in this Borough to accommodate 30 Belgian Refugees, not of the peasant type, but of the middle class and tradespeople …

I shall be glad if you can arrange for these refugees to arrive in Tunbridge Wells on Friday afternoon, and if you will kindly let me know prior to their arrival the names, relationships, and any other particulars relating to those sent, and the time of arrival.

You will no doubt arrange before they are sent that they are medically examined and have a clean bill of health.

It seems that medical fitness was of concern to the authorities dealing with the arrivals from Belgium, not just those refugees who had been wounded in fighting. At an early volunteer meeting for this project, we looked at refugee centre registration forms which inquired of the refugees, ‘If vaccinated, when?’

In 1910 the only vaccine was for smallpox. Although in 1914, Belgian bacteriologist Octave Gengou had just developed the first Pertussis (whooping cough) vaccine, the next vaccines came slowly – Diphtheria in 1926, Tetanus (1938), DTP combined vaccine (1948), and Measles (1968). Smallpox vaccine had been developed during the 18th century. Lady Mary Wortley Montague (incidentally a visitor to Tunbridge Wells along with her husband Sir Edward Wortley Montague) inoculated her son in 1718 on a trip to the Ottoman Empire. The process involved using live smallpox virus in the pus taken from a smallpox blister in a mild case of the disease and introducing it into scratched skin of a previously uninfected person to promote immunity to the disease. The safer technique developed by Edward Jenner in 1796, of vaccination from cowpox, gained favour. Should anyone wonder why these people were so keen to develop this protection, a few facts: an estimated 400,000 Europeans were killed by the disease annually during the closing years of the 18th century, and it was responsible for a third of all blindness Moreover 20-60 percent of those infected, and over 80 percent of infected children, died of the disease.

Finding out that the British government introduced compulsory smallpox vaccination by an Act of Parliament in 1853, and parents fined if they didn’t have their babies vaccinated, lead me to wonder about Victorian, or rather pre-1914, health care. The 19th century saw many improvements to medicine and health. However, patients were expected to pay for their own treatment. Some free hospitals were available, and friendly societies offered health insurance schemes.

Previously, in the 1840s, the government had offered free and voluntary vaccinations targeted at the poor. This effort failed when people, wary of the effects of the vaccination, refused it. Thus, the Compulsory Vaccination Act was passed and with it was born a strong anti-vaccination movement. Several changes in the law lead to it becoming no longer compulsory in 1907.

Regarding general health, we know that the Belgians were looked after when they arrived in Tunbridge Wells. Some were treated at the general hospital (shown below). In July 1916, the local Belgian ‘Colony’ celebrated their National Day by honouring not only the ladies of the Mayor’s Refugee Committee but also three local doctors – Wilson, Smith and Guthrie – who had ministered to the refugees free of charge.

General hospital, early 20th Century, by James Richard (courtesy of Tunbridge Wells Museum)

Dr Claude Wilson was born in 1860 in Liverpool, to Quaker parents and did his medical training in Edinburgh. He married Annette Guthrie, the sister of Dr Guthrie, around 1887 and the couple lived at 9 Church Road, next door to the Guthries. Wilson was a general practitioner (GP) but he also undertook duties at the general hospital, which was a charitable body. He was particularly interested in cardiology.

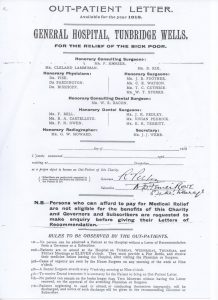

Thomas Clement Guthrie (also a GP) was from Edinburgh. His wife, Nora was the sister of Susan Power (a local poor law guardian and member of the borough refugees’ committee). This was not the only family connection between the doctors and the committee: the Wilsons’ daughter Mary married the brother of Aimee Elizabeth Moinet, another committee member. Dr Guthrie was a honorary surgeon at the Tunbridge Wells general hospital in 1918, as the document below shows.

Outpatient letter (private collection)

The third doctor honoured was another GP, Dr Peter Colin Campbell Smith who lived at 4 Upper Grosvenor Road in 1914. His wife Dorothee Caroline Marie Antoinette Francoise de Sales was born in Norway and they married in Gibraltar in 1899 and their first son was born some 9 months later in Morocco. In 1901 the family were in Darlington and by 1911 had moved to Tunbridge Wells. It was reported in February 1915 that Dr Campbell Smith had contracted ‘severe blood-poisoning in his attendance on Belgian refugees’ but fortunately he recovered.

No doubt other medical and non-medical staff looked after the patients, but they unfortunately remain nameless.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smallpox

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vaccination_Act

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/victorian_medicine_01.shtml

John Cunningham (ed) The Shock of War (Tunbridge Wells Civic Society, 2014)

Sarah Wise, The Blackest Streets: The Life and Death of a Victorian Slum (Vintage, 2009).

Ancestry.co.uk

Kelly’s Directory, 1914.