In an article in The Independent yesterday, Adrian Hamilton makes the point that our public galleries and museums are neglecting their core collections, and devoting their energies to mounting exhibitions instead.

The reason, he argues, is ecomomics: exhibitions are more likely to attract media interest, with specific themes uniting the display, and also more interest from the public. People will also buy merchandise associated with a particular exhibition: the Van Gogh tea-towel or Dali catalogue. All these factors combine to mean one thing: more money.

With the abolishment of entry fees under Labour back in 2001, musuems and galleries are having to work hard to compensate for cuts in funding. Exhibitions and featured attractions are more likely to bring visitors through the revolving doors than focusing on the objects that are a part of the institution’s regular collection.

As Hamilton says, “Free entry has brought a huge expansion in the customer base. But it has been at a cost of directing museums to showmanship and to commercial avenues of income at the expense of concentrating on their own collections and adding to them. The funds available for purchase are derisory. The attention of keepers has been directed to the numbers passing through the doors.”

He proposes that museums and galleries should consider re-introducing entry fees, with reductions for the young and the elderly, which would then allow them to provide exhibitions driven not by the need to generate revenue, but to showcase what the gallery or museum already owns.

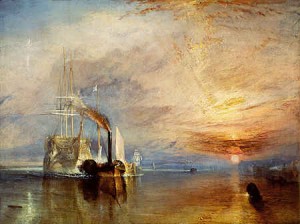

As someone who loves the National Gallery and National Portrait Gallery, both of which are free, this option scares me. I have two very young children with whom I want to share my love of Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne and Crivelli’s Annunciation when they are old enough: I want their imaginations to be lit up by sacred paintings from the Renaissance, whorls of colour in Turner, Stubbs’ rearing horses or Monet’s floating lilies. If I had to pay for us all to visit each time, this would be costly and would, I’m sure, discourage many from visiting.

I can, however, see the point, though: museums and galleries need to bring paying visitors through the doors to keep themselves going.

Would you pay entry fees to galleries and museums if, by doing so, it guaranteed their continued existence: or would it put you off ?