Written by Thomas Stephens.

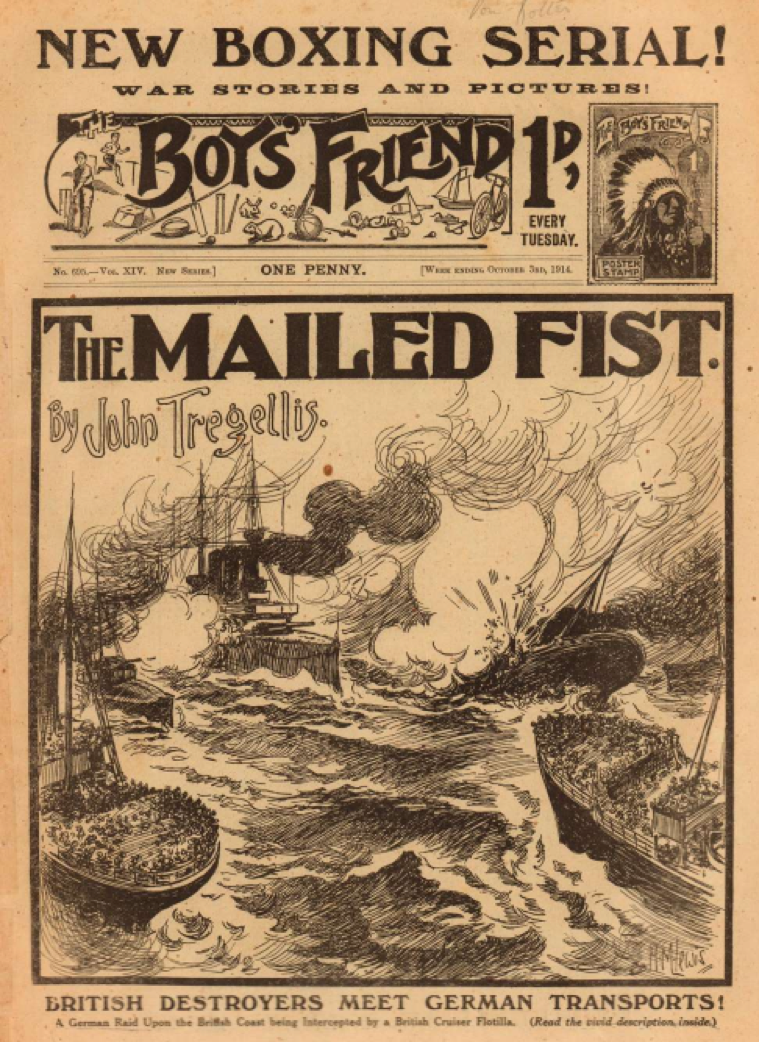

British boys’ authors writing during the First World War embraced the conflict as a new arena for their fictional heroes. Stories about the war were at a premium from 1914 onwards, and many authors also took the opportunity to use their publications to mobilise youth to help in the war effort. Those writing about the war for boys got information about the conflict using information from a combination of newspapers, official propaganda, personal knowledge, rumour, and imagination. In 1914 and 1915, a flood of stories focusing on the conflict appeared in boys’ literature. But by 1916, many story papers such as the Boys’ Own Paper, Magnet, and Boys’ Friend returned to primarily running humorous public-school stories or colonial adventures. These topics gave readers an escape from the sombre matter of industrialised warfare. Wartime inflation and loss of staff also made returning to easily reprintable stories a sensible idea. Many novels and some adventure serials, like Chums, continued to feature narratives about the front throughout the conflict.

Despite recruiting children to aid the nation, boys’ authors usually sheltered readers from the real horrors of war. However, they quickly reused the trope of “barbarous” Germans, often taken from propaganda targeting adults, in their own work. Almost every boys’ war serial recounting exploits at the front referenced German atrocities in Belgium. Some depicted the events generally, recounting tales of Germans massacring civilians or sexually assaulting women and girls. Others went more in-depth, for instance, a Chums adventure serial recounted a factual account of enemy soldiers executing civilians at St. Trond in Belgium only three months after the event occurred. Whatever truth such stories might contain, boys’ authors also reported rumours or reprinted outlandish claims circulating in the adult press. Their stories included horrific accounts of Germans crucifying prisoners, slicing the hands from French civilians, and even assertions that the German army drove the Ottoman Empire to massacre its Armenian inhabitants. German atrocities in France and Belgium in the opening months of the conflict provoked anger and fear, but as Adrian Gregory has argued, it was attacks on Britain in 1915 that spurred the greatest anger. Propagandists capitalised on this very real fury by producing a wave of propaganda that dehumanised Germans.

British boys’ authors were not exempt from this wave of hatred against Germans. Most embraced official propaganda and popular narratives that suggested Germans were physically or mentally different from the ‘civilised’ people. Examining boys’ story papers shows how engrained these wartime images of the Germans as “other” became within Britain during the war. The presence of adult propaganda narratives demonising Germans within much of boys’ literature is even more striking when one examines texts not directly discussing the course of the war or fighting at the front lines. The wartime work of Charles Hamilton is an excellent example of this trend.

Charles Hamilton was one of the most prolific boys’ authors in history. His work appeared frequently in magazines from Amalgamated Press like The Gem and Boys’ Friend. Right-wing and anti-intellectual, Hamilton focused his written efforts during the war on recounting the adventures of fictional boys’ public schools. Like many other boys’ authors penning low-brow fiction during this period, Hamilton was never afraid to mock or belittle “foreigners.” As was the case for others writing during the First World War, Hamilton represented the barbaric “Hun” to readers as a factual representation of Germans generally.

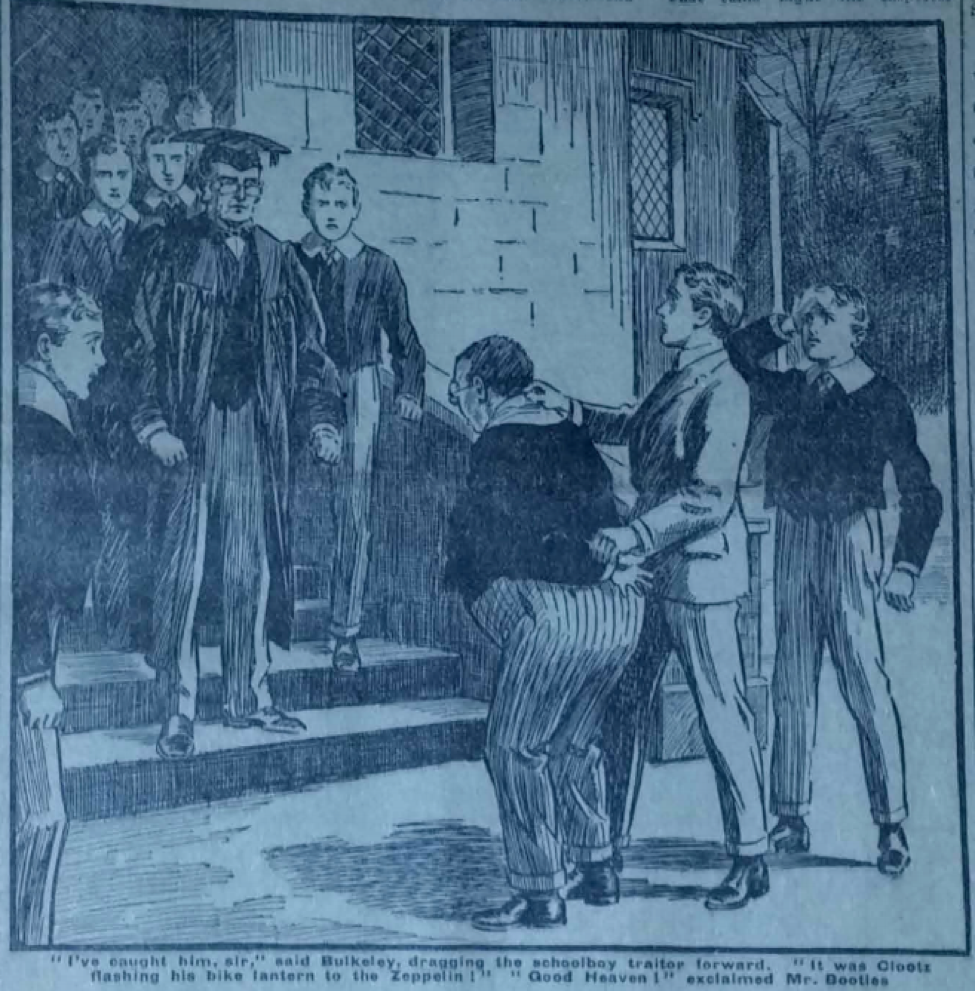

One such example is Hamilton’s school story, “The Hate of the Hun.” It appeared in the magazine The Boy’s Friend in January 1916. Supposedly written by “Owen Conquest,” one of Hamilton’s many pen-names, the story recounted the humorous adventures of English schoolboys and their interactions with a German schoolmate named Heinrich Clootz.

In Hamilton’s tale, Clootz’s “Hun” tendencies are apparent despite his age or his attempts to blend in with the English boys. Instead of his usual Teutonic practices, Clootz restrains himself to only occasionally chuckling at the thought of murdered babies, singing the “Hymn of Hate” against England, or assaulting smaller boys. Hamilton humorously suggests that exercising such restraint was a hardship for Clootz.

Only a noble boy named Jimmy Silver and his overly trusting headmaster attempt to welcome Clootz at the school. The other English schoolmates distrust the youth because of his German parentage. However, when Jimmy catches Clootz signalling Zeppelins to bomb the boarding school, everyone realises Clootz is like all Germans. As the police drag Clootz away to an uncertain fate, he reemphasizes his difference from the English boys by screaming he would gladly die if he could only slaughter his school-fellows.

Pondering their interactions with Clootz, the schoolboys conclude that Germans are simply born without morals. Hamilton reiterates this point, reminding his readers that all Germans possess a “kink in their brains.” This flaw made them natural bullies and traitors. Clootz and his countrymen shared this with the Germans in the Zeppelin bombing the school, the “bestial barbarians that recked not that their bombs fell alike upon helpless women and little children.” No German, Hamilton told his readers “could [understand] it was wrong to do as his animal-like nature led him.” Hamilton made it clear that one had to use violence to make a German comprehend anything. For instance, the schoolboys suggested Clootz would only understand bombing children was wrong when British politicians began the retaliatory bombardment of German cities.

Stories like Hamilton’s reminded readers that Germans were, and always had been, evil. Such ideas became commonplace in the adult world during the conflict. An excellent example of adult propaganda reproduced in children’s stories was Louis Raemaeker’s Germanophobic cartoons republished in Edward Parrot’s The Child’s History of the War.

It is unsurprising that boys’ adventure stories about the war at the front depicted German barbarism. Such accounts justified the need for Britain to fight and the necessity of killing Germans in less chivalrous industrialised warfare by pointing to German behaviour. They also relied upon news or rumours about the war to construct believable narratives for their audience, emphasising the depravity of Germans. Fictional narratives set on the home front such as “The Hate of the Hun” needed no such source material about the conflict. These stories were set in familiar surroundings or used common events imagined or experienced by many readers. Though these tales used the war as less of a plot point than battlefield adventure stories, they still vilified Germans in the same way as those focused on the conflict itself. Whether a narratives’ focus was the battlefield or Britain, or even if it had no connection with the war when these stories referenced German characters it was almost always in an extremely negative way. While various authors explained German depravity as having different root causes, ranging from head-size to culture, the consensus throughout boys’ literature was the same: Germans were evil. The consistent demonization of Germans in these boys’ stories shows how ubiquitous propaganda narratives about barbaric Germans became during the First World War.

Thomas Stephens is a History PhD Student at the University of Indiana, Bloomington. His research interests include propaganda and the imagination of violence in Britain during First World War and children’s experience of the conflict.

Further Reading

Kelly Boyd, Manliness and the Boys’ Story Paper in Britain 1855-1940 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003)

Adrian Gregory, The Last Great War: British Society and the First World War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008)

Rosie Kennedy, The Children’s War: Britain, 1914-1918 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014)