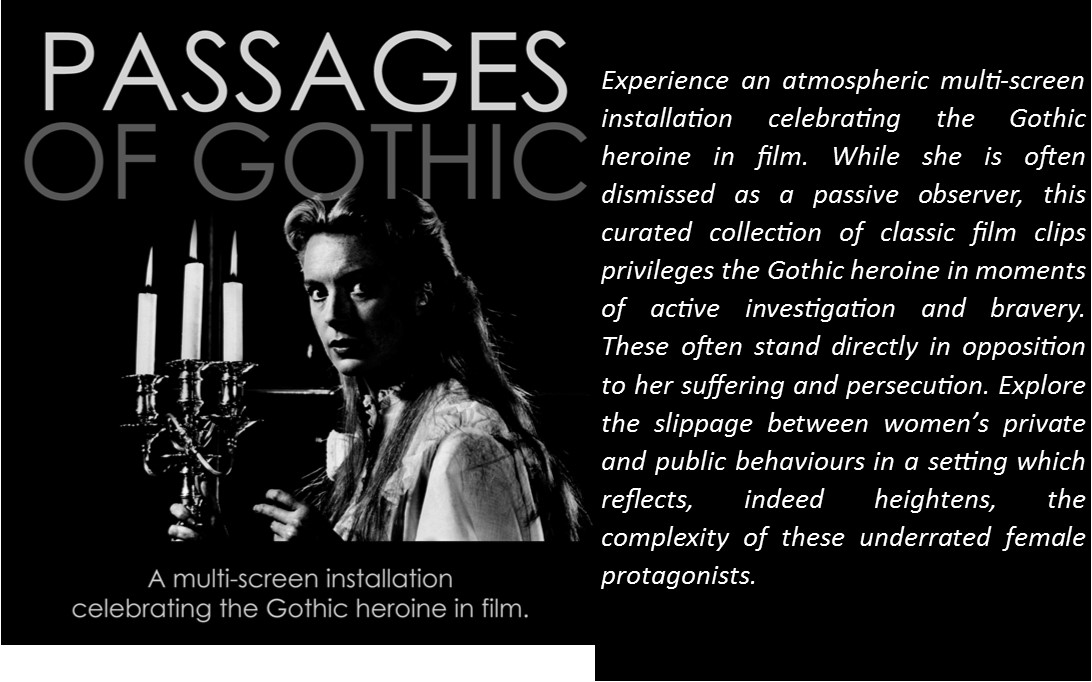

Following the intense and enjoyable screening of the Melodrama Research Group’s contribution to the International Festival of Projections, here is a version of Frances’ wonderful Project Notes for Passages of Gothic.

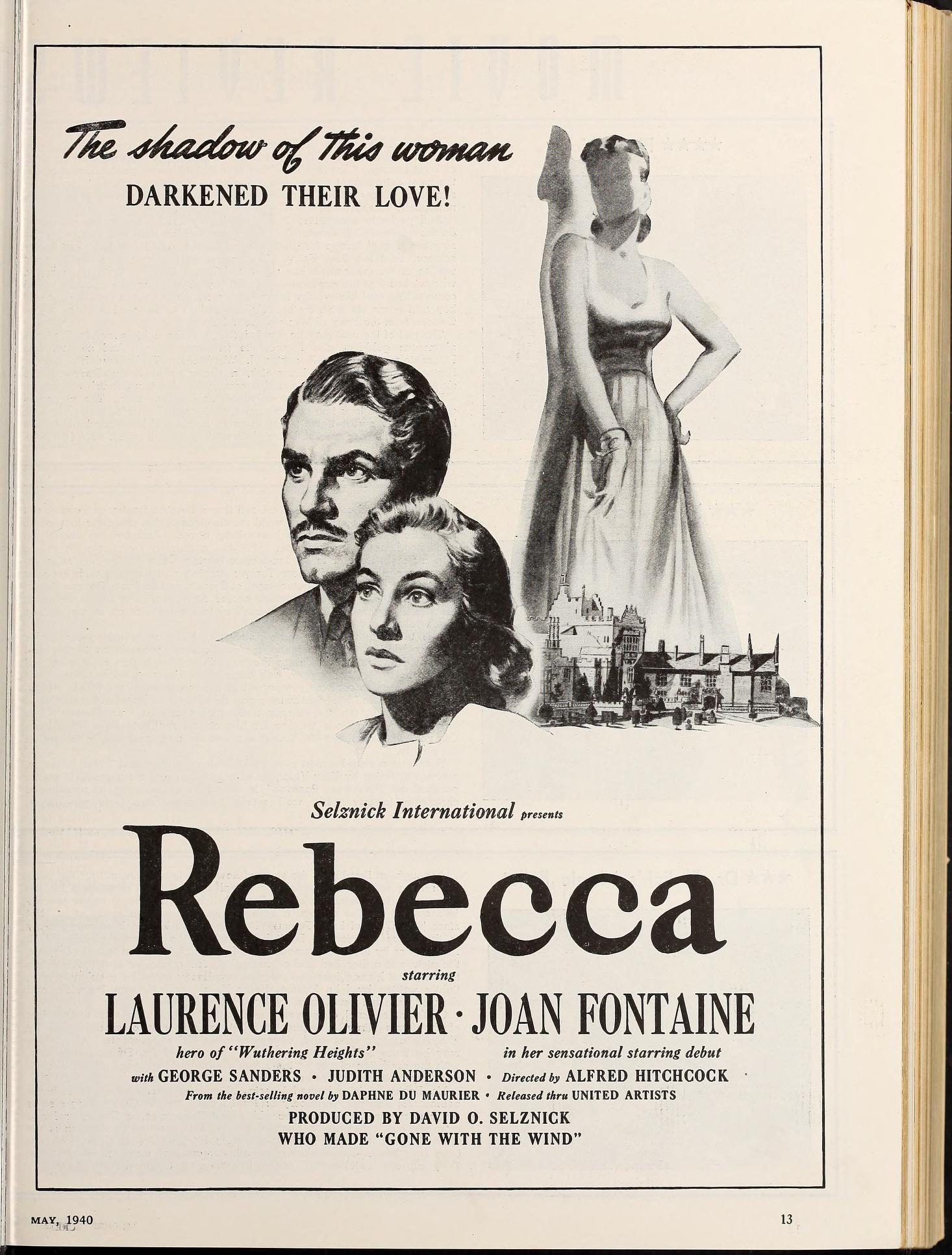

Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940) is often cited as the first in a cycle of films emerging in Hollywood in the 1940s labelled as ‘Gothic’. These films – which have also been called ‘melodramas’, ‘women’s films’ and ‘female film noirs’ – feature similar narratives focusing on the central female protagonist: the Gothic heroine. In all these films, the Gothic heroine encounters the old dark house which harbours a sinister secret which the heroine must investigate, often in fear for her life. This threat usually emanates from a male love interest, or is sometimes presented as the oppression of a larger patriarchal society. These films – which also include Gaslight (1944), Secret Beyond the Door (1947) and Sleep, My Love (1948) – feature remarkably consistent motifs, including keys, staircases, images of the heroine alone in the dark and the threat of the domestic space. Significantly, the study of film history reveals that these tropes are not isolated to the Hollywood Gothics of the 1940s but, in fact, continue to inform and appear within the Gothic cinema of today. This installation shall highlight and explore these similarities.

This project focuses on the female performance in these films in order to show the narrative and visual agency given to characters who are often seen as passive subjects and victims. Whilst the Gothic heroine may indeed be threatened by her male counterpart or dangerous environment, these stories encourage us to identify with the female lead, admiring her bravery. We engage with these films’ narratives by aligning with the Gothic heroine and her experiences. In particular, our exploration of space is mediated by the Gothic heroine’s actions. This project will illuminate how such investigation consistently takes place within the domestic space: the safety of a home is transformed into the mysterious and dangerous space of the old dark house. Comparing these films demonstrates how the Gothic heroine is often framed within the in-between places of a house: the stairwell, the hallway or the doorway. These thresholds are spaces which blur the boundaries between the public and private spheres of a home, in much the same way these Gothic narratives present a slippage between the real and the imagined; the everyday and the supernatural.

It is for these reasons that Passages of Gothic is presented within Eliot Dining Hall. Eliot College is a building which is also both a public and private space, containing professional forums for study (lecture halls, seminar rooms and offices) and private rooms (student bedrooms and kitchens). The Hall is at the heart of the college and provides passageways between these distinct locations. The Hall’s distinctive appearance has also historically made it the site for public and private events, and its scale is evocative of the intimating houses the Gothic heroine explores in these films. As the name of this event suggests, Passages of Gothic therefore invites you to immerse yourself into the Gothic heroine’s world.

The film shall play on three separate screens and is divided into six ‘chapters’. Together, these chapters create a narrative which is reflective of the fictional journey taken by the Gothic heroine: the heroine enters the house; she is forced the investigate strange occurrences; she is threatened by someone or something; and she may or may not survive her ordeal. In Passages of Gothic these six chapters are:

- “I dreamt I went to Manderley again”: Gothic introductions

- Inside the house

- “I should go mad if I stay!”

- Lights in the darkness

- Women in peril

- “Why?”

Passages of Gothic is the culmination of the research conducted by the Melodrama Research Group into female performance, stardom, genre conventions, Gothic tropes and the representations of the heroine on-screen. This installation showcases the re-emergence of Gothic tropes – in a remarkably consistent fashion – across film history, highlighting the importance of the Gothic heroine within this. Our celebration of the Gothic’s strong, brave, and active heroines contributes to an important, broader research question: why, after 75 years, do these representations of the Gothic heroine persist in the 21st Century?

Top image: Lies Lanckman and Ann-Marie Fleming (image from The Innocents (1961); Main text: Frances Kamm; Bottom image: Crimson Peak (2015)

Credits:

Passages of Gothic

Project organiser: Sarah Polley

Project’s writer and content provider: Frances Kamm

Project’s editor: Alaina Piro Schempp

Lead technician: Lies Lanckman

Promotions: Ann-Marie Fleming

IT Support: Oana Maria Mazilu

Contributor: Tamar Jeffers McDonald

Contributor: Katerina Flint-Nicol

The Gothic Heroines

Joan Fontaine in Rebecca (1940)

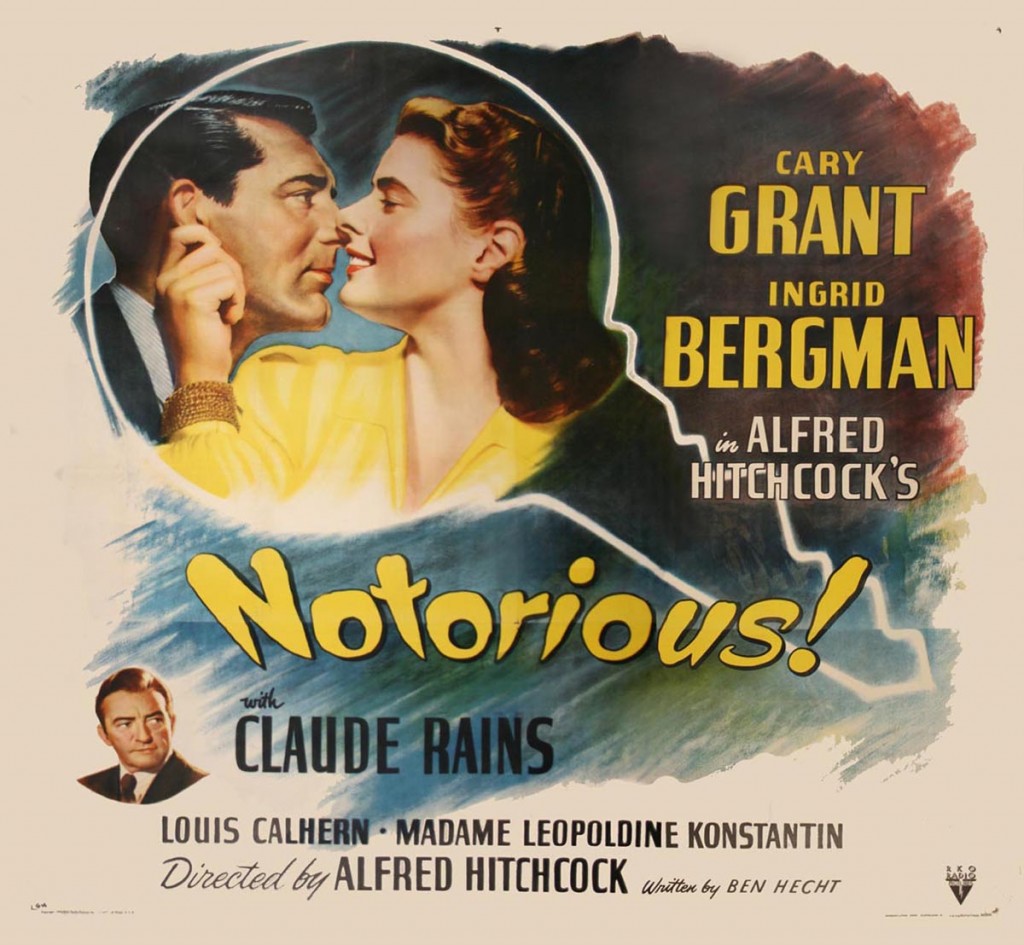

Ingrid Bergman in Gaslight (1944)

Dorothy McGuire in The Spiral Staircase (1945)

Joan Bennett in Secret Beyond the Door (1947)

Claudette Colbert in Sleep, My Love (1948)

Deborah Kerr in The Innocents (1961)

Katharine Ross in The Stepford Wives (1975)

Shelley Duvall in The Shining (1980)

JoBeth Williams in Poltergeist (1982)

Sigourney Weaver in Aliens (1986)

Michelle Pfeiffer in What Lies Beneath (2000)

Nicole Kidman in The Others (2001)

Naomi Watts and Laura Harring in Mulholland Drive (2001)

Belén Rueda in The Orphanage (El Orfanato) (2007)

Rebecca Hall in The Awakening (2011)

Chiara D’Anna and Sidse Babett Knudsen in The Duke of Burgundy (2014)

Mia Wasikowska in Crimson Peak (2015)

The Melodrama Research Group

The Melodrama Research Group is sponsored by the Centre for Film and Media Research within the School of Arts, University of Kent. The MRG is a cross-faculty group of academics who are interested in exploring the ideas surrounding melodrama as a hotly-contested topic. The group meets for regular screenings and debates, maintains a dynamic blog and has hosted research events. The group brings together scholars from various disciplines in order to foster collaborative networks for studying this pervasive but challenging genre.

https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/

International Festival of Projections

This is a new, free arts festival taking place at the University of Kent from 18-20 March 2016. Spread across both the Canterbury and Medway campus, and with satellite events within the Canterbury City Centre, the festival celebrates the exciting and varied theme of projections.

http://www.kent.ac.uk/projections/