Comments on Robert Siodmak’s The Spiral Staircase (1946) included the film’s temporal and geographical settings; its use of early cinema entertainment; the film’s plot; its heroine; the source novel; feminism and the film’s characters; the couple; the melodrama genre and more specifically gothic tropes such as the staircase.

Our discussion began with appreciation for the film’s opening. This occurs just after the shadowy shot of a woman descending a spiral staircase over which the credits roll. After establishing a suitably creepy atmosphere, the film proceeds to communicate the film’s time and place. Small town America is conveyed by wide streets and the date narrowed to sometime in the 1910s judging by the dirt road, horses and carts, and characters’ costumes. The date is further pinned down by the screening of a modern attraction – a short silent motion picture, The Kiss. (This might be an extract from Ulysses Davis’ 1914 version starring William Desmond Taylor, although several shorts with the same name were produced in the 1910s.)

The heroine of the film, young mute Helen  (Dorothy McGuire), is attending the screening and this aligns us with her as film goers. It also creates a certain expectation of romance within the film – once more for both us and Helen. We especially liked this depiction of film history within a film text, and were impressed by the inclusion of a woman playing live piano accompaniment. Soon the murder of a disabled young woman is committed in her rooms above the theatre. The masterly fluid use of space between the lower and higher levels contrasts to the disjuncture inherent in our viewing of those enjoying an entertainment and the serious crime taking place upstairs. Even the dramatic nature of the short overtaken by ‘real’ events.

(Dorothy McGuire), is attending the screening and this aligns us with her as film goers. It also creates a certain expectation of romance within the film – once more for both us and Helen. We especially liked this depiction of film history within a film text, and were impressed by the inclusion of a woman playing live piano accompaniment. Soon the murder of a disabled young woman is committed in her rooms above the theatre. The masterly fluid use of space between the lower and higher levels contrasts to the disjuncture inherent in our viewing of those enjoying an entertainment and the serious crime taking place upstairs. Even the dramatic nature of the short overtaken by ‘real’ events.

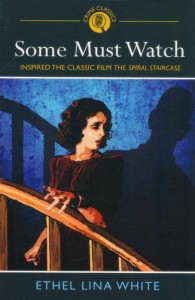

While the alignment of us with Helen, and the other film goers, draws us into the action the dissonance between audience experiences (silent vs sound) separates us. This led us to ponder some key differences between the source material (Ethel Lina White’s Some Must Watch 1933) and the film. The action has moved from rural UK to small-town America (despite the inclusion of recognisable British actors Elsa Lanchester and Sara Allgood). The heroine is now a mute which places her in the path of the serial killer murdering disabled women. These women begin 10 years earlier with a woman with learning difficulties, and more recently one with a scarred face (a strong comment on the linking of women and beauty), another woman with learning difficulties, a woman with mobility issues, one who refused to love the murderer (presumably this is seen to show a lack of judgement, though of course we know differently), and lastly possibly Helen, who is mute. More significantly the film is placed around twenty years earlier than the novel. Instances of feminism in the film are therefore displaced onto earlier times and the fact that the heroine literally, and not just metaphorically, has no voice is also connected to the time of women’s suffrage. We also noted that conduct literature of the time advocated all women being quiet – raising her hat to get attention rather than shouting.

While the alignment of us with Helen, and the other film goers, draws us into the action the dissonance between audience experiences (silent vs sound) separates us. This led us to ponder some key differences between the source material (Ethel Lina White’s Some Must Watch 1933) and the film. The action has moved from rural UK to small-town America (despite the inclusion of recognisable British actors Elsa Lanchester and Sara Allgood). The heroine is now a mute which places her in the path of the serial killer murdering disabled women. These women begin 10 years earlier with a woman with learning difficulties, and more recently one with a scarred face (a strong comment on the linking of women and beauty), another woman with learning difficulties, a woman with mobility issues, one who refused to love the murderer (presumably this is seen to show a lack of judgement, though of course we know differently), and lastly possibly Helen, who is mute. More significantly the film is placed around twenty years earlier than the novel. Instances of feminism in the film are therefore displaced onto earlier times and the fact that the heroine literally, and not just metaphorically, has no voice is also connected to the time of women’s suffrage. We also noted that conduct literature of the time advocated all women being quiet – raising her hat to get attention rather than shouting.

We discussed the instances  of feminism in the film at some length. The heroine is not saved by a man, but a woman. Specifically Helen’s saviour is her elderly, seemingly bed-ridden and cranky employer Mrs Warren (Ethel Barrymore). Not only does Mrs Warren urge Helen to leave the house for her own safety but she shoots her stepson, Professor Warren (George O’Brien), when she realises he has committed these heinous crimes. Although this action might seem surprising – especially in terms of the character’s limited mobility – several important factors have been established earlier. We see Mrs Warren with a gun which she then manages to somehow hide and her hunting past is evidenced by the various animal trophies in her room which include several stuffed birds, tusks and a prominently placed tiger rug. The latter is focuses on when Helen almost trips over it. Mrs Warren explicitly claims it as her ‘kill’ and notes that her husband said she was ‘not as beautiful’ as his first wife but that she was a much better ‘shot’ – a strength he greatly admired. As well as establishing Mrs Warren’s strong character the various stuffed animals add to the creepy setting by adding more watching pairs of eyes – death pervades not just the town, but the house too.

of feminism in the film at some length. The heroine is not saved by a man, but a woman. Specifically Helen’s saviour is her elderly, seemingly bed-ridden and cranky employer Mrs Warren (Ethel Barrymore). Not only does Mrs Warren urge Helen to leave the house for her own safety but she shoots her stepson, Professor Warren (George O’Brien), when she realises he has committed these heinous crimes. Although this action might seem surprising – especially in terms of the character’s limited mobility – several important factors have been established earlier. We see Mrs Warren with a gun which she then manages to somehow hide and her hunting past is evidenced by the various animal trophies in her room which include several stuffed birds, tusks and a prominently placed tiger rug. The latter is focuses on when Helen almost trips over it. Mrs Warren explicitly claims it as her ‘kill’ and notes that her husband said she was ‘not as beautiful’ as his first wife but that she was a much better ‘shot’ – a strength he greatly admired. As well as establishing Mrs Warren’s strong character the various stuffed animals add to the creepy setting by adding more watching pairs of eyes – death pervades not just the town, but the house too.

Mrs Warren also provides a vital insight into the motivations of the killer when she comments, early on, that her husband thought men could only be men if they were toting guns. This places the blame firmly at the feet of her dead husband and this is later confirmed by Professor Warren’s ‘justification’ to Helen. He specially states that his father would be proud he is ridding the world of the ‘afflicted’. (Notably not weak people – there are no male victims only those doubly ‘afflicted’ by disfigurement or disability and the being of the female gender.)

Professor Warren’s half-brother Steve’s behaviour is also critiqued. His attentions are seen to bother his brother’s secretary, Blanche, with their final meeting including him telling her that he enjoys watching her cry. He considers this sadistic behaviour common to all men since women’s expressions of their emotions make the male gender feel ‘superior’. Specifically he cautions Blanche not to be ‘melodramatic’.

Professor Warren’s half-brother Steve’s behaviour is also critiqued. His attentions are seen to bother his brother’s secretary, Blanche, with their final meeting including him telling her that he enjoys watching her cry. He considers this sadistic behaviour common to all men since women’s expressions of their emotions make the male gender feel ‘superior’. Specifically he cautions Blanche not to be ‘melodramatic’.

The film cannot be viewed as a straightforward criticism of patriarchy, however, as it switches between approaches. The romantic subplot with Doctor Parry expresses this most strongly. Helen and Doctor Parry’s status as a romantic couple is far more straightforward than either Rebecca or Sorry, Wrong Number. While Maxim de Winter and Lenore’s husband are killers (and significantly wife-killers) Doctor Parry is a decent man of conviction. He does not express his love for Helen other than a brief kiss, but it is commented on by Mrs Warren in front of the pair. Mrs Warren attempts to displace the responsibility for taking Helen away onto Doctor Parry, though this is unsuccessful. This view of traditional gender roles is also held by Helen. Her fantasy is of her wedding to Doctor Parry. She pictures this taking place at the house but this turns into a nightmare when she is unable to utter ‘I do’. It is also notable that Doctor Parry takes it upon himself to ‘cure’ Helen of her lack of speech becoming, albeit briefly, another threatening man in the narrative as she shouts at her. In fact Helen only regains her voice after the shock of Mrs Warren shooting her stepson.

This view of traditional gender roles is also held by Helen. Her fantasy is of her wedding to Doctor Parry. She pictures this taking place at the house but this turns into a nightmare when she is unable to utter ‘I do’. It is also notable that Doctor Parry takes it upon himself to ‘cure’ Helen of her lack of speech becoming, albeit briefly, another threatening man in the narrative as she shouts at her. In fact Helen only regains her voice after the shock of Mrs Warren shooting her stepson.

We also spoke about the film’s effective creation and dissipation of suspense. As Helen walks home after the murder at the theatre she hears something. Arming herself with a heft tree branch she is relieved to discover the source of the sound was merely a rabbit. As Helen approaches the house she drops her door key and as she stoops to collect it we are afforded a glimpse of a man Helen does not see. Thankfully she reaches the front door and gains access to the house. This is not without a sense of foreboding though as Helen is being watched by various statutes and ‘faces’ in the furniture. Our concerns are made more concrete as it is soon revealed that someone has deliberately opened one of the windows whish the housekeeper Mrs Oates insists was earlier shut. Another moment of suspense is created as off-camera we hear Mrs Oates cry out as she walks out. The culprit – a bulldog- is soon revealed. Such switches (and those critiquing and supporting patriarchy) are part of the ‘rhythm’ of the film’s melodrama.

More specifically gothic tropes such as a woman carrying a candlestick exploring the space of the house also appear. While three women (Mrs Oates, Blanche and Helen) perform this action, only the heroine is actively investigating. Mrs Oates is seeking brandy in the cellar (which it is later revealed her employer Professor Warren has deliberately let her steal so that she will be incapacitated and unable to interfere in his crimes) and Blanche is simply retrieving her suitcase so she can leave. Helen alone is investigating by going looking for the missing Blanche. Shortly after Helen finds Blanche murdered, Steven appears on the scene and Helen is proactive in taking action – she utilises Mrs Oates’ candle trick to trick him into the cellar and lock the door. Interestingly other aspects of the heroine wearing a nightgown (see The Innocents 1961) is fulfilled by Blanche and later Mrs Warren who has places her house coat over her bedclothes when she shoots her stepson.

More specifically gothic tropes such as a woman carrying a candlestick exploring the space of the house also appear. While three women (Mrs Oates, Blanche and Helen) perform this action, only the heroine is actively investigating. Mrs Oates is seeking brandy in the cellar (which it is later revealed her employer Professor Warren has deliberately let her steal so that she will be incapacitated and unable to interfere in his crimes) and Blanche is simply retrieving her suitcase so she can leave. Helen alone is investigating by going looking for the missing Blanche. Shortly after Helen finds Blanche murdered, Steven appears on the scene and Helen is proactive in taking action – she utilises Mrs Oates’ candle trick to trick him into the cellar and lock the door. Interestingly other aspects of the heroine wearing a nightgown (see The Innocents 1961) is fulfilled by Blanche and later Mrs Warren who has places her house coat over her bedclothes when she shoots her stepson.

Staircases also play an important role. We noted the striking high angle shot which details Mrs Warren at the top of the staircase shooting her stepson several times. Her powerful position cats her as judge and executioner. More generally, character are often ascending and descending them. It is useful to bear in mind Mary Ann Doane’s comment on the staircase’s significance as a space of ‘transition’ (1987, pp. 135-6: https://melodramaresearchgroupextra.wordpress.com/2015/12/02/melodrama-reading-doanes-paranoia-and-the-specular/) We particularly noted the difference between the use of the huge front formal staircase (more usually used by the family) and the shadowy back stairs (for the servants). While the former were ascended a lot the back stairs were mostly descended. The fact the prominently placed mirror occupied liminal space by appearing half way up the formal staircase was also discussed. We found the killer POV shots occurring here especially tense, reminding us of Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960) and Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960).

particularly noted the difference between the use of the huge front formal staircase (more usually used by the family) and the shadowy back stairs (for the servants). While the former were ascended a lot the back stairs were mostly descended. The fact the prominently placed mirror occupied liminal space by appearing half way up the formal staircase was also discussed. We found the killer POV shots occurring here especially tense, reminding us of Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960) and Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960).

You can find more information on Some Must Watch here: https://melodramaresearchgroupextra.wordpress.com/?s=some+must+watch)

As ever, do log in to comment or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to add your thoughts.