Posted by Sarah

Our post-screening discussion ranged widely and encompassed: analysis of Joan Crawford/Sadie’s first appearance; Sadie’s costume, especially compared to the other female characters; Crawford’s performance – in particular the many layers of performance; a comparison between Mildred in Of Human Bondage and Sadie in Rain; noting of Crawford and Bette Davis’ contrasting acting styles; Sadie’s antagonistic relationship with the reformer Davidson; Walter Huston’s performance; the film’s happy ending. Throughout discussion was illuminated by reference to Maugham’s short story and the 1928 silent version of the film which starred Gloria Swanson.

We began with discussion of one of the film’s most memorable moments: Joan Crawford’s first appearance. It is especially significant in terms of female representation that Crawford/Sadie is introduced by shots of her body, which themselves are fragmented. (See Laura Mulvey’s ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ for more on the fragmented female body and the ‘male gaze’[i].) First Crawford/Sadie’s right, heavily bangled, hand almost thumps a door post. This is quickly followed by a shot of her left hand making a similar gesture towards the opposite door post. Then her right foot is planted heavily on the ground. A similar action shortly occurs with the left. This is more than the usual star entrance as it makes such a bold statement. Indeed the character/star punctuates the scene with the forceful movement of her limbs. In addition, the stance this pose would constitute if we were to see it in full looks incredibly ungainly, with Crawford/Sadie’s feet seemingly planted quite firmly apart. As such it appears less than ladylike. Finally a shot of Crawford/Sadie’s face gives us a view of her insolently sulky mouth which is accentuated by the heavily outlined lips. Through Crawford/Sadie’s dangling cigarette she utters her first word, a huskily intoned ‘Boys’. It is an astonishingly powerful, and not at all subtle, introduction of both the star (Crawford) and the character (the prostitute Sadie). It was mentioned that a similar scene does not occur in the 1928 silent film starring Gloria Swanson.

We began with discussion of one of the film’s most memorable moments: Joan Crawford’s first appearance. It is especially significant in terms of female representation that Crawford/Sadie is introduced by shots of her body, which themselves are fragmented. (See Laura Mulvey’s ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ for more on the fragmented female body and the ‘male gaze’[i].) First Crawford/Sadie’s right, heavily bangled, hand almost thumps a door post. This is quickly followed by a shot of her left hand making a similar gesture towards the opposite door post. Then her right foot is planted heavily on the ground. A similar action shortly occurs with the left. This is more than the usual star entrance as it makes such a bold statement. Indeed the character/star punctuates the scene with the forceful movement of her limbs. In addition, the stance this pose would constitute if we were to see it in full looks incredibly ungainly, with Crawford/Sadie’s feet seemingly planted quite firmly apart. As such it appears less than ladylike. Finally a shot of Crawford/Sadie’s face gives us a view of her insolently sulky mouth which is accentuated by the heavily outlined lips. Through Crawford/Sadie’s dangling cigarette she utters her first word, a huskily intoned ‘Boys’. It is an astonishingly powerful, and not at all subtle, introduction of both the star (Crawford) and the character (the prostitute Sadie). It was mentioned that a similar scene does not occur in the 1928 silent film starring Gloria Swanson.

The costume was also commented upon at length. Crawford/Sadie wore a tight gingham dress, with a wide white belt further accentuating her curves, for much of the film. The accessories worn at this point, and a little further into the film, are of great significance. Despite the stifling heat of the island, Sadie has a fur draped around her neck and a hat which resembled swan feathers covering most of her head. Sadie is clearly a woman who cares about appearances, and indeed her own performance in everyday life.

Crawford/Sadie’s first appearance is memorable not just due to the energy and the  somewhat startlingly heavily made up face, but the fact a very similar scene occurs towards the film’s end. Before this happens though, Sadie undergoes a spiritual and physical transformation. She is seen with minimal make-up, brushed-out hair and wearing darker, more modest clothes. When she reverts back to type this is reflected by the return to her previous outfit, make-up and hairstyle. This is a great example of Jane Gaines’ assertion that dress often tells the woman’s story.[ii] Crawford/Sadie is re-introduced by shots which once more fragment her body. It was also noted that Crawford/Sadie’s costume marks her out from the other women in the film – the actresses Beulah Bondi and Kendall Lee playing the characters Mrs Davidson

somewhat startlingly heavily made up face, but the fact a very similar scene occurs towards the film’s end. Before this happens though, Sadie undergoes a spiritual and physical transformation. She is seen with minimal make-up, brushed-out hair and wearing darker, more modest clothes. When she reverts back to type this is reflected by the return to her previous outfit, make-up and hairstyle. This is a great example of Jane Gaines’ assertion that dress often tells the woman’s story.[ii] Crawford/Sadie is re-introduced by shots which once more fragment her body. It was also noted that Crawford/Sadie’s costume marks her out from the other women in the film – the actresses Beulah Bondi and Kendall Lee playing the characters Mrs Davidson  and Mrs Macphail. The clothes of the latter pair are more modest than Sadie’s and tend to be in blocks of one colour in contrast to the gingham patterned dress. Similar delineation between the female characters also occurred with Davis/Mildred in Of Human Bondage in relation the actresses Kay Johnson and Frances Dee who play Philip’s other love interests Norah and Sally.

and Mrs Macphail. The clothes of the latter pair are more modest than Sadie’s and tend to be in blocks of one colour in contrast to the gingham patterned dress. Similar delineation between the female characters also occurred with Davis/Mildred in Of Human Bondage in relation the actresses Kay Johnson and Frances Dee who play Philip’s other love interests Norah and Sally.

Crawford’s performance also prompted much discussion. It was noted that physically  she looked quite a bit like Gloria Swanson at certain points. Lies revealed that this might well have spilled over into performance too as Crawford had yet to find her style and imitated Swanson’s earlier portrayal. Indeed comparisons between Crawford and other female stars in melodramas (primarily Swanson and Davis) were found to be useful in examining Crawford’s performance. This

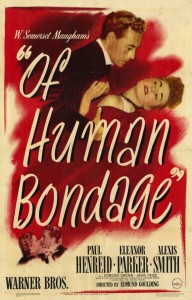

she looked quite a bit like Gloria Swanson at certain points. Lies revealed that this might well have spilled over into performance too as Crawford had yet to find her style and imitated Swanson’s earlier portrayal. Indeed comparisons between Crawford and other female stars in melodramas (primarily Swanson and Davis) were found to be useful in examining Crawford’s performance. This  is made easier by the fact Of Human Bondage and Rain contain several parallels. Both are based on Somerset Maugham stories and were produced at a similar time (1932 and 1934). In addition both the female characters are prostitutes for at least some of the narrative, and marked something of a departure for Davis and Crawford. There are, however, several big differences between the performances of Davis and Crawford, and the characters they play.

is made easier by the fact Of Human Bondage and Rain contain several parallels. Both are based on Somerset Maugham stories and were produced at a similar time (1932 and 1934). In addition both the female characters are prostitutes for at least some of the narrative, and marked something of a departure for Davis and Crawford. There are, however, several big differences between the performances of Davis and Crawford, and the characters they play.

Crawford is required to perform on several levels. There is the bold front Sadie assumes as the prostitute joking with potential clients – brazenly drinking whisky straight out of the bottle in public and dancing with abandon. Sadie’s insincere acknowledgment of her sins is juxtaposed with her contrasting sincere repentance. When Sadie finally reverts to type, this bears similarities to her very first appearance also has significant differences. We particularly noted the transformation scene in which Sadie gains religious enlightenment. Its importance is indicated through the staging on the main staircase (important to several melodramas) and the camerawork. Sadie’s adversary, the religious reformer Alfred Davidson (Walter Huston) stands solidly at the top of the stairs while Sadie looks up from the bottom. She climbs the stairs, ready to take him to task. There is little movement apart from the ascension of the stairs, though Crawford/Sadie’s worrying of the top banister indicates her distress. She descends the steps and appears ready to go. Davidson is seen is close shot standing still and a cut to Sadie reveals that she is also riveted to the spot. The moment in which Sadie is  transformed occurs shortly after and is visible onscreen. The camera lingers on her beautifully lit, tear-stained face as a look of realisation starts in her eyes and then spreads across her features. The camera then moves out to give a better view of Sadie and Davidson, now pictured together in the shot. The scene ends with an attention-pulling crane shot which exits the building.

transformed occurs shortly after and is visible onscreen. The camera lingers on her beautifully lit, tear-stained face as a look of realisation starts in her eyes and then spreads across her features. The camera then moves out to give a better view of Sadie and Davidson, now pictured together in the shot. The scene ends with an attention-pulling crane shot which exits the building.

There is further opportunity for Crawford to show her acting skills. When William Gargan’s character O’Hara (referred to as ‘Handsome’ by Sadie – another example of her playing the gallery) soon returns to take Sadie away to a new life Crawford plays the scene rather robotically to start with. She speaks in a monotone and refuses to look at O’Hara/Gargan. Total disengagement is not possible though as Handsome continues and Sadie briskly pushes him away, raising her voice as she does do. Crawford ably performs Sadie’s conflicting desires as she struggles to resist temptation. The shift between the obvious exaggerated performance Sadie puts on for the surrounding men and the more quiet moments (which occur later on in the film when we first see her alone) help to create a complex and sympathetic character. It was mentioned that perhaps the shifts between different levels of performance by Crawford were what led to the negative contemporaneous critical reviews. Though, as Lies noted, Crawford’s performance has been viewed more favourably since. (Apparently there is still little written on Rain, and pre-code Joan, however.)

There is further opportunity for Crawford to show her acting skills. When William Gargan’s character O’Hara (referred to as ‘Handsome’ by Sadie – another example of her playing the gallery) soon returns to take Sadie away to a new life Crawford plays the scene rather robotically to start with. She speaks in a monotone and refuses to look at O’Hara/Gargan. Total disengagement is not possible though as Handsome continues and Sadie briskly pushes him away, raising her voice as she does do. Crawford ably performs Sadie’s conflicting desires as she struggles to resist temptation. The shift between the obvious exaggerated performance Sadie puts on for the surrounding men and the more quiet moments (which occur later on in the film when we first see her alone) help to create a complex and sympathetic character. It was mentioned that perhaps the shifts between different levels of performance by Crawford were what led to the negative contemporaneous critical reviews. Though, as Lies noted, Crawford’s performance has been viewed more favourably since. (Apparently there is still little written on Rain, and pre-code Joan, however.)

By contrast, while Davis’ performance in Of Human Bondage is by no means on one-level, we rarely get a glimpse of different aspects of what might be considered the ‘real’ Mildred. Of course the notion of a ‘real’ character is a very fraught and abstract concept, more so when star image is added to the mix. Here it is very noticeable though, since Mildred the character is always performing; she puts on an accent and gives herself airs to appear more refined and she manipulates Philip, and other men, by exaggerated dismissive gestures or flirtatious behaviour. In addition, Davis/Mildred is always moving – facially and bodily – a whole performance in itself. There are two main scenes in Of Human Bondage when Mildred is not performing. The first is the tirade she unleashes  against Philip which is very physical and exaggerated. The second is the unglamorous scene in which she is seriously ill and escorted from her lodging to hospital. Here she is incapable of moving much. In both of these scenes Mildred’s real self is revealed as truly horrible: in the first her vindictive character is fully vented and in the second she is physically hideous.

against Philip which is very physical and exaggerated. The second is the unglamorous scene in which she is seriously ill and escorted from her lodging to hospital. Here she is incapable of moving much. In both of these scenes Mildred’s real self is revealed as truly horrible: in the first her vindictive character is fully vented and in the second she is physically hideous.

We found it interesting that there was such a variance between Crawford’s, at times, fairly restrained playing with little movement and Davis’s constant movement and big gestures in these two melodramas. Especially because melodrama is a genre in which performance is often thought to be related to exaggeration. Lies highlighted the difference between Crawford’s naturalistic and Davis’ theatrical approaches. In addition, it was thought that Crawford’s instinctive playing coincided with Sadie’s almost primitive awareness of danger. As soon as, at first sight, Sadie sees Davidson looking intently at her she appears to recognise the danger, first returning the look and then glancing down. The different types of performances are also related to the fact that while Davis is seen primarily as an actress, Crawford is largely remembered as a star with little range.

Of course part of the difference is due to the characters and the fact that while Mildred is not the central character in Of Human Bondage, Sadie is Rain’s protagonist. There are many other Crawford and Davis performances in melodramas available for us to compare and contrast to get a better idea of trends. (This could be a very fruitful, and enjoyable, line for future screenings!) It reveals that as well as the infinite variety of melodrama which has been evident in our screenings (male melodrama, animation, theatrical adaptations, Honk Kong cinema etc), even this rather narrow subgenre of melodrama, the Woman’s Film, is diverse.

In addition to the sympathy created by Crawford’s performance, it was noted that the film, like the short story, promoted Sadie’s position as the correct one. The Doctor, who is central in Maugham’s story, is seen to be sympathetic to her plight. But he is not the main male character in the film, neither is this role filled by Crawford/Sadie’s love interest Handsome: instead the reformer Davidson takes centre stage. His anguish in his moment of weakness is one of the film’s key moments. As well as being pictured (it was only ever implied in the story) this is heightened by the film’s wonderfully atmospheric use of sound. The beating of rain which has been persistent for much of the film reaches its pitch and is accompanied by diegetic drumming. Contrast is present between the changeability in Crawford/Sadie’s performance and situation and Davidson’s immovable morality. Huston conveys this formidably, with a stolidly still uprightness in which the framing colludes.

In addition to the sympathy created by Crawford’s performance, it was noted that the film, like the short story, promoted Sadie’s position as the correct one. The Doctor, who is central in Maugham’s story, is seen to be sympathetic to her plight. But he is not the main male character in the film, neither is this role filled by Crawford/Sadie’s love interest Handsome: instead the reformer Davidson takes centre stage. His anguish in his moment of weakness is one of the film’s key moments. As well as being pictured (it was only ever implied in the story) this is heightened by the film’s wonderfully atmospheric use of sound. The beating of rain which has been persistent for much of the film reaches its pitch and is accompanied by diegetic drumming. Contrast is present between the changeability in Crawford/Sadie’s performance and situation and Davidson’s immovable morality. Huston conveys this formidably, with a stolidly still uprightness in which the framing colludes.

We also observed the way Sadie was contrasted to other characters, especially the female ones. While the Doctor’s wife, like him, is low-key, Mrs Davidson is as aggressive as her husband in demanding Sadie’s salvation. Mrs Davidson is shown to be vindictive, rather than Christian, in her attitude though. She exaggerates when telling her husband that Sadie spoke back to her. We also thought it was fascinating that Mrs Davidson is the subject of the film’s last shot. After Sadie walks off with Handsome (a happy ending not present in the story, but almost obligatory in Hollywood narratives) the camera stays with the newly-widowed Mrs Davidson clasping her hands to her face.

We also observed the way Sadie was contrasted to other characters, especially the female ones. While the Doctor’s wife, like him, is low-key, Mrs Davidson is as aggressive as her husband in demanding Sadie’s salvation. Mrs Davidson is shown to be vindictive, rather than Christian, in her attitude though. She exaggerates when telling her husband that Sadie spoke back to her. We also thought it was fascinating that Mrs Davidson is the subject of the film’s last shot. After Sadie walks off with Handsome (a happy ending not present in the story, but almost obligatory in Hollywood narratives) the camera stays with the newly-widowed Mrs Davidson clasping her hands to her face.

While Sadie does have a happy ending, which in some ways domesticates her, we thought it significant that she still appears in many ways similar to the Sadie we saw at the very start of the film. We concluded our discussion by mentioning how unusual it was for a sinning Hollywood heroine to end a film unreformed, especially after the  stricter policing of the Hays Code in 1934. Two films starring Barbara Stanwyck are good examples of pre and post-code attitudes to female character and crime. In the pre-code The Miracle Woman (1931) we see Florence Fallon

stricter policing of the Hays Code in 1934. Two films starring Barbara Stanwyck are good examples of pre and post-code attitudes to female character and crime. In the pre-code The Miracle Woman (1931) we see Florence Fallon  move from con artist evangelist to member of the Salvation Army. This clearly contrasts to Rain’s treatment of Sadie. Unsurprisingly, Stanwyck’s character Lee Leander in a later film, Remember the Night (1940), is punished for her shoplifting crimes by being sent to prison.

move from con artist evangelist to member of the Salvation Army. This clearly contrasts to Rain’s treatment of Sadie. Unsurprisingly, Stanwyck’s character Lee Leander in a later film, Remember the Night (1940), is punished for her shoplifting crimes by being sent to prison.

Many thanks to Lies for providing such a wonderful introduction to Joan and Rain.

[i] Mulvey, Laura. “Visual pleasure and narrative cinema.” Feminisms: an anthology of literary theory and criticism (1975): 438-48.

[ii]Gaines, Jane. “Costume and Narrative: how dress tells the woman’s story.” Fabrications: costume and the female body (1990): 180-211.

Do, as always, log in to comment or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk

wood’s greatest female stars – Bette Davis and Joan Crawford – in the roles of the Hudson sisters provoked comment at the time. For example, both the film’s trailer and Variety’s review find the teaming of the stars significant. The trailer touches on the matter of star image as it warns the potential audience that What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? does not resemble the pair’s previous (separate) films. Meanwhile, Variety opines that the casting of Davis and Crawford in retrospect seems like a ‘veritable prerequisite to putting Henry Farrell’s slight tale of terror on the screen’. It certainly led to great returns at the box office: the relatively low budget (just over $1 million) film grossed $9 million.[1]

wood’s greatest female stars – Bette Davis and Joan Crawford – in the roles of the Hudson sisters provoked comment at the time. For example, both the film’s trailer and Variety’s review find the teaming of the stars significant. The trailer touches on the matter of star image as it warns the potential audience that What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? does not resemble the pair’s previous (separate) films. Meanwhile, Variety opines that the casting of Davis and Crawford in retrospect seems like a ‘veritable prerequisite to putting Henry Farrell’s slight tale of terror on the screen’. It certainly led to great returns at the box office: the relatively low budget (just over $1 million) film grossed $9 million.[1] The film’s production has earned its place in Hollywood folklore in the intervening years. This is primarily due to the assertion that this marked the culmination of Davis and Crawford’s long-running, and some might say melodramatic, feud. Like many Hollywood stories though, this is only partially true. Several sources note the one-upmanship that took place during filming. For example, Bob Thomas’ biography of Crawford details some of the ‘conflict’ between the stars (pp. 224-229). Charlotte Chandler’s ‘personal’ biography of Crawford concludes that the ‘legendary feud between the two may have been just that – a legend’ dreamed up by Baby Jane’s publicity people which the stars both ended up believing (p. 248). Whenever the feud started, and for whatever reason, Davis had very definite ideas about a sequel to the film: “I’ll tell you the first scene. It’ll be a scene of this one,’ pointing at herself, ‘putting flowers on that one’s grave” (p. 250). (A follow-up film Hush… Hush, Sweet Charlotte, was made in 1964 – but with Olivia de Havilland replacing an ill Crawford part-way through).That until Baby Jane Crawford was not really on Davis’ radar is supported by Davis’ autobiography The Lonely Life, published in 1962, which does not even mention Crawford. Davis rectifies this, with relish, in her 1987 post Baby Jane memoir This ‘n That.

The film’s production has earned its place in Hollywood folklore in the intervening years. This is primarily due to the assertion that this marked the culmination of Davis and Crawford’s long-running, and some might say melodramatic, feud. Like many Hollywood stories though, this is only partially true. Several sources note the one-upmanship that took place during filming. For example, Bob Thomas’ biography of Crawford details some of the ‘conflict’ between the stars (pp. 224-229). Charlotte Chandler’s ‘personal’ biography of Crawford concludes that the ‘legendary feud between the two may have been just that – a legend’ dreamed up by Baby Jane’s publicity people which the stars both ended up believing (p. 248). Whenever the feud started, and for whatever reason, Davis had very definite ideas about a sequel to the film: “I’ll tell you the first scene. It’ll be a scene of this one,’ pointing at herself, ‘putting flowers on that one’s grave” (p. 250). (A follow-up film Hush… Hush, Sweet Charlotte, was made in 1964 – but with Olivia de Havilland replacing an ill Crawford part-way through).That until Baby Jane Crawford was not really on Davis’ radar is supported by Davis’ autobiography The Lonely Life, published in 1962, which does not even mention Crawford. Davis rectifies this, with relish, in her 1987 post Baby Jane memoir This ‘n That. Regardless of any melodramatic off-screen tales surrounding What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? the American Film Institute (AFI) Catalog categorises the film text as melodrama. The AFI defines melodramas as ‘fictional films that revolve around suffering protagonists victimized by situations or events related to social distinctions, family and/or sexuality, emphasizing emotion’. [2]

Regardless of any melodramatic off-screen tales surrounding What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? the American Film Institute (AFI) Catalog categorises the film text as melodrama. The AFI defines melodramas as ‘fictional films that revolve around suffering protagonists victimized by situations or events related to social distinctions, family and/or sexuality, emphasizing emotion’. [2]