Our discussion on Young and Innocent covered its relationship to both traditional and male melodrama; the main characters Erica (Nova Pilbeam) and Robert (Derrick De Marney) and the stars who played them; the film as an adaptation of Josephine Tey’s novel A Shilling For Candles; another of its director Alfred Hitchcock’s films from around the time.

We were especially struck by the melodramatic tone of the first scene, a direct contrast to the jaunty, 42nd Street-style music, which plays over the opening credits. In the first scene, a man (Guy, played by George Curzon) and woman (Christine Clay, played by Pamela Carme) have a blazing row. This is filmed straightforwardly, privileging the gestures of the characters. These gestures are rather broad, but the staginess is explained later in the narrative as we learn that both participants are performers – a musician and a film star. The lack of inventive camerawork means that we focus on the dialogue in which Guy accuses his wife, Christine, of infidelity. As the argument reaches its peak, sound is used imaginatively. In addition to music underscoring the characters’ emotions, the weather is also dramatic. A diegetic clap of thunder obligingly replaces the, presumably colourful, insult Guy directs at Christine. Drama conveyed by landscape and music is extended to the scene in which Robert Tisdall (Derrick de Marney) finds Christine’s strangled body on the beach. The lapping of waves at Christine’s lifeless, swimming costume clad, body is joined by another upswell of music.

the scene in which Robert Tisdall (Derrick de Marney) finds Christine’s strangled body on the beach. The lapping of waves at Christine’s lifeless, swimming costume clad, body is joined by another upswell of music.

Other aspects of the film can be more usefully connected to the male melodrama’s staple elements of mystery, violence, and chase. There is the central mystery of who killed Christine, and the whereabouts of the presumed murder weapon – the belt from Robert’s raincoat. Chase also plays a large part in the film as Robert soon goes on the run. Violence is implied in the hands-on method of the murder, even though we do not witness it. There is also the threat of violence, as we may fear for the life of young Erica (Nova Pilbeam); a woman who becomes bound up with Robert, and the film’s elements of mystery and chase. More traditional melodrama is returned to as Erica begins to regret helping Robert and fears for what will become of members of her family if she cannot return to them. Later Erica is reduced to tears again. The relationship between Robert and Erica has grown and, after a brief separation, they are reunited but she is distressed at the thought of losing him again.

chase. More traditional melodrama is returned to as Erica begins to regret helping Robert and fears for what will become of members of her family if she cannot return to them. Later Erica is reduced to tears again. The relationship between Robert and Erica has grown and, after a brief separation, they are reunited but she is distressed at the thought of losing him again.

The rhythm of the film is very important. There are points of high drama: a woman has been killed, Robert faces the death penalty if he is found guilty, and Erica faces expulsion from her family if she keeps true to him. There are car chases, a near train crash, and collapsing mineworks. But there are also slower moments. Notably there is comic relief we might compare to earlier stage melodrama which often used stock comic secondary char

The rhythm of the film is very important. There are points of high drama: a woman has been killed, Robert faces the death penalty if he is found guilty, and Erica faces expulsion from her family if she keeps true to him. There are car chases, a near train crash, and collapsing mineworks. But there are also slower moments. Notably there is comic relief we might compare to earlier stage melodrama which often used stock comic secondary char acters. In Young and Innocent these are Robert’s surprisingly breezy solicitor, the incompetent uniformed police who are forced to travel in a cart with some pigs, Erica’s younger brothers, Erica’s Aunt (Mary Clare) and Uncle (Basil Radford), and Will the friendly china-mending tramp (Edward Rigby).

acters. In Young and Innocent these are Robert’s surprisingly breezy solicitor, the incompetent uniformed police who are forced to travel in a cart with some pigs, Erica’s younger brothers, Erica’s Aunt (Mary Clare) and Uncle (Basil Radford), and Will the friendly china-mending tramp (Edward Rigby).

These secondary characters are incorporated more fully into the narrative than is often the case in traditional melodrama since Robert and Erica frequently interact with them. Robert steals his solicitor’s spectacles to effect a Clark Kent-style transformation in order to escape. He also inadvertently kicks a policeman in the head as he and Erica flee their hiding place – a remote mill. Will is enlisted by Erica and Robert to help them locate the real killer.

Some of these secondary characters are particularly attached to Erica. Her quarrelsome, but endearing, brothers and her aunt and uncle provide her with context. A visit to Erica’s Aunt and Uncle especially gives Erica and Robert the chance to extend the gentle badinage they have already begun to engage in as they drive through the countryside. The comic awkwardness of Erica introducing a new friend to her family is taken further. Erica’s Aunt questions Robert and, understandably due to his fugitive status, he invents a name for himself. He and Erica then have to improvise around this. When separately interrogated by Erica’s Aunt, they provide Robert with different professions: while Erica states Robert is an architect, he claims to write music. The use of fake names (and Robert’s is perhaps deliberately ridiculous) and the invention of identities brought to mind screwball comedy films. In films belonging to the screwball subgenre, generally thought to have begun in the United

Some of these secondary characters are particularly attached to Erica. Her quarrelsome, but endearing, brothers and her aunt and uncle provide her with context. A visit to Erica’s Aunt and Uncle especially gives Erica and Robert the chance to extend the gentle badinage they have already begun to engage in as they drive through the countryside. The comic awkwardness of Erica introducing a new friend to her family is taken further. Erica’s Aunt questions Robert and, understandably due to his fugitive status, he invents a name for himself. He and Erica then have to improvise around this. When separately interrogated by Erica’s Aunt, they provide Robert with different professions: while Erica states Robert is an architect, he claims to write music. The use of fake names (and Robert’s is perhaps deliberately ridiculous) and the invention of identities brought to mind screwball comedy films. In films belonging to the screwball subgenre, generally thought to have begun in the United States in 1934, the main couple engage in ‘role play’ as part of creating their own world. Robert and Erica’s use of imagination is also employed when it is not necessary to put others off the scent. When they are alone at the cold and dark train station they begin to fantasise about a delicious dinner and a fancy hotel.

States in 1934, the main couple engage in ‘role play’ as part of creating their own world. Robert and Erica’s use of imagination is also employed when it is not necessary to put others off the scent. When they are alone at the cold and dark train station they begin to fantasise about a delicious dinner and a fancy hotel.

We also spent a fair bit of time discussing the two main characters, Erica and Robert, and the actors who played them. We considered the possibility that Erica was a suffering heroine, at risk from violence at the hands of Robert. In fact, this does not seem applicable to Erica. We were impressed with the spirit she showed throughout the film, and which is established in her first appearance. Erica breezes confidently into the police station at which Robert is being held. While Erica’s assurance is partly due to her status as the daughter of the chief constable, it is also influenced by her forceful personality which belies her youth. On seeing that Robert has fainted, E

We also spent a fair bit of time discussing the two main characters, Erica and Robert, and the actors who played them. We considered the possibility that Erica was a suffering heroine, at risk from violence at the hands of Robert. In fact, this does not seem applicable to Erica. We were impressed with the spirit she showed throughout the film, and which is established in her first appearance. Erica breezes confidently into the police station at which Robert is being held. While Erica’s assurance is partly due to her status as the daughter of the chief constable, it is also influenced by her forceful personality which belies her youth. On seeing that Robert has fainted, E rica swiftly administers physical aid and offers alcohol in an effort to revive him. Erica is equally able to take charge at home by keeping her younger brothers in line – even when one produces a dead rat at the dinner table.

rica swiftly administers physical aid and offers alcohol in an effort to revive him. Erica is equally able to take charge at home by keeping her younger brothers in line – even when one produces a dead rat at the dinner table.

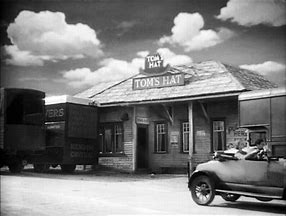

Erica is not limited to spaces connected to her father, though, as her ownership of a car allows her to travel wherever she pleases. It is significant that she alone seems able to persuade her old heap to work – her mobility is only possible because of her determination. Erica’s access to a car means that she can help Robert in his escape and subsequent investigation. She is also an active participant in this. She leaves Robert waiting outside as their quest for Robert’s missing raincoat leads them to Tom’s Hat café. While inside she chats naturally with the regulars, mostly lorry drivers, finding out that Will, a china-mending tramp, was seen wearing Robert’s coat. The release of this information leads to fight breaking out. During this, to Robert’s surprise, Erica is able to take care of herself. She also stands up to Robert as she insists, on more th

Erica is not limited to spaces connected to her father, though, as her ownership of a car allows her to travel wherever she pleases. It is significant that she alone seems able to persuade her old heap to work – her mobility is only possible because of her determination. Erica’s access to a car means that she can help Robert in his escape and subsequent investigation. She is also an active participant in this. She leaves Robert waiting outside as their quest for Robert’s missing raincoat leads them to Tom’s Hat café. While inside she chats naturally with the regulars, mostly lorry drivers, finding out that Will, a china-mending tramp, was seen wearing Robert’s coat. The release of this information leads to fight breaking out. During this, to Robert’s surprise, Erica is able to take care of herself. She also stands up to Robert as she insists, on more th an one occasion, that her dog is not left behind. It is Erica’s knowledge of first aid which unmasks the killer. Will has revealed that the man who gave him Robert’s coat had a twitch. When Erica rushes in to help a musician who has collapsed at the Grand Hotel she realises that he too has a twitch. Her identification leads to him taking full responsibility for the crime, thus exonerating Robert.

an one occasion, that her dog is not left behind. It is Erica’s knowledge of first aid which unmasks the killer. Will has revealed that the man who gave him Robert’s coat had a twitch. When Erica rushes in to help a musician who has collapsed at the Grand Hotel she realises that he too has a twitch. Her identification leads to him taking full responsibility for the crime, thus exonerating Robert.

We also thought a little about the fact that the film places Erica centrally. Nova Pilbeam receives star, above the title, billing. This mention of Pilbeam reminds us the that characters in films are connected to the stars who play them. Pilbeam was indeed young, aged 18 at the time of Young and Innocent’s release, and had only appeared in a handful of films. The characters she portrayed in these can be usefully compared to the independent Erica. In Berthold Viertel’s Little Friend (1934) Pilbeam played a girl who becomes aware that her parent’s marriage is disintegrating. The same year she appeared in Alfred Hitchcoc

We also thought a little about the fact that the film places Erica centrally. Nova Pilbeam receives star, above the title, billing. This mention of Pilbeam reminds us the that characters in films are connected to the stars who play them. Pilbeam was indeed young, aged 18 at the time of Young and Innocent’s release, and had only appeared in a handful of films. The characters she portrayed in these can be usefully compared to the independent Erica. In Berthold Viertel’s Little Friend (1934) Pilbeam played a girl who becomes aware that her parent’s marriage is disintegrating. The same year she appeared in Alfred Hitchcoc k’s The Man Who Knew Too Much – as the kidnapped daughter of Leslie Banks and Edna Best. Just prior to Young and Innocent, Pilbeam starred in Tudor Rose (1936, Robert Stevenson) as Lady Jane Grey, ‘the Nine Days’ Queen’, who was executed at the age of 17.

k’s The Man Who Knew Too Much – as the kidnapped daughter of Leslie Banks and Edna Best. Just prior to Young and Innocent, Pilbeam starred in Tudor Rose (1936, Robert Stevenson) as Lady Jane Grey, ‘the Nine Days’ Queen’, who was executed at the age of 17.

The struggling youths Pilbeam had previously played mitigates Erica’s independent spirit. Furthermore, the title of the film on its US release, The Girl Was Young, underlines that Erica is the Young and Innocent of the UK film’s title. While in the film Pilbeam’s independence is championed, the outside context of her earlier films and the film’s titles on UK and US release, potentially place her at more harm from Robert.

The struggling youths Pilbeam had previously played mitigates Erica’s independent spirit. Furthermore, the title of the film on its US release, The Girl Was Young, underlines that Erica is the Young and Innocent of the UK film’s title. While in the film Pilbeam’s independence is championed, the outside context of her earlier films and the film’s titles on UK and US release, potentially place her at more harm from Robert.

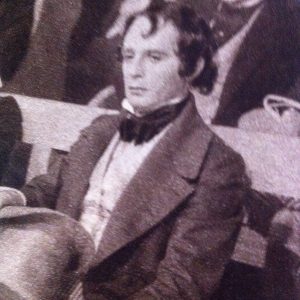

This consideration that Erica might be a ‘woman in peril’ also needs to be contextualised in reference to Robert’s character, de Marney’s billing, and his previous films. Although Robert is suspected of murder, the only violent act we see him commit is an accidental one – the kicking of a policeman in the head. Robert manages to stay calm while he is on the run, and his role-play with Erica is good-humoured. When reflecting on how a star’s previous films affect his or her current role, it is worth noting that de Marney started in silent films in 1928. Because he had appeared in more films than Pilbeam by 1937 (19 to her 3), it is less easy to provide a summary of the types he played – both larger and smaller roles – in lower and higher budget films. He does not seem to have been attached to villainous characters, however. In Edward Godal’s ‘quota quickie’ Adventurous Youth (1928) de Marney played the main role of a heroic man fighting for his village during the Mexican Revolution. In the year of Young and Innocent’s release, de Marney, appeared in the small role of Young Disraeli in Herbert Wilcox’s Victoria the Great. De Marney played the same character in Wilcox’s sequel, Sixty Glorious Years (1938), and was connected to the role earlier in his stage career. It has been importa nt to look at Robert’s character, and at de Marney’s previous heroic and statesmanlike roles when considering whether Erica is in danger, but it is also true that Erica and Pilbeam’s earlier roles hold more sway. She is after all, more centrally placed. While Pilbeam is given star billing, de Marney is only afforded a ‘with’ credit, which is places below both Pilbeam and the film’s title.

nt to look at Robert’s character, and at de Marney’s previous heroic and statesmanlike roles when considering whether Erica is in danger, but it is also true that Erica and Pilbeam’s earlier roles hold more sway. She is after all, more centrally placed. While Pilbeam is given star billing, de Marney is only afforded a ‘with’ credit, which is places below both Pilbeam and the film’s title.

In addition to thinking about how the characters in the films are portrayed and the connections we can draw to the actors, they are further illuminated in comparison to Josephine Tey’s novel. The film is a fairly free adaptation. It changes the identity of the murderer. In the novel this is revealed to be Christine’s brother, Herbert Gotobed, after her husband, Lord Edward Champneis, is first suspected. Christine’s brother does not appear in the film, and her husband, now renamed Guy and redeployed as a musician, is the guilty party. Guy does not play a large part in the film, though he is involved in the key moments which bookend it: he argues with Christine in the opening scene, leading to her murder, and he confesses to his crime in the film’s last moments. The revelation of his guilt just prior to this is especially arresting. The camera sweeps from its initial focus on guests in the lobby of the Grand Hotel to the crowded dance floor, the group of the black-face orchestra, and finally to the twitching drummer – Guy. As well as demonstrating the impressive range of the camera, it is perfectly timed with the sound, as the close up coincides with the line of the song ‘no one can like the drummer can’.

We also discussed the fact that the film only adapted the first half of the novel – Erica’s meeting with Detective Inspector Alan Grant and her subsequent undertaking to prove Robert’s innocence. The second half of Tey’s book moves to Grant’s uncovering of the real culprit. In the film, which changes the identity of the murderer, the matters are tied together: finding Robert’s missing raincoat leads to the identification of a twitching man who used the belt to kill Christine. The film’s change in scope also means that it pulls focus. While Grant provides the through-line for the novel, he is barely present in the film, as the renamed ‘Inspector Kent’ (John Longdale) who briefly interrogates Robert at the police station. We were able to recognise that ‘Kent’ was Grant as the dialogue Erica shares with Grant in the novel is allocated to Kent. The film’s main detectives are instead Erica and Robert.

We also discussed the fact that the film only adapted the first half of the novel – Erica’s meeting with Detective Inspector Alan Grant and her subsequent undertaking to prove Robert’s innocence. The second half of Tey’s book moves to Grant’s uncovering of the real culprit. In the film, which changes the identity of the murderer, the matters are tied together: finding Robert’s missing raincoat leads to the identification of a twitching man who used the belt to kill Christine. The film’s change in scope also means that it pulls focus. While Grant provides the through-line for the novel, he is barely present in the film, as the renamed ‘Inspector Kent’ (John Longdale) who briefly interrogates Robert at the police station. We were able to recognise that ‘Kent’ was Grant as the dialogue Erica shares with Grant in the novel is allocated to Kent. The film’s main detectives are instead Erica and Robert.

Because the film’s aspect of investigation is very narrow – finding the lost raincoat – it does not explore the motive for Christine’s murder. I have already mentioned that Guy only bookends the film. Christine is afforded even less attention. This is not the case in the novel, which provides lots of information about Christine’s public image (in fan magazines) before it delves into her past.

Although the film removes some characters, and provides less information about others, it supplies new characters too. These are mostly Erica’s relatives – her brothers, her Aunt and Uncle – and add to the film’s comedy. While this bolsters Erica’s role, it mitigates her self-sufficiency. By contrast, Robert is given less of a back story in the film than the novel which details a previous name change so that he was able to receive an inheritance. The fact that in the film Robert accompanies Erica on the investigations she pursues alone in the novel impacts on her status as an independent woman. In the novel, Will is a menacing figure, who threatens Erica when she visits his isolated caravan alone. Will is altered to a more genial type in the film – he even gets dressed up and dances with Erica at the Grand Hotel. In addition, Robert’s own solo hunt for Will at a boarding house, gives Erica less opportunity to display her bravery.

Although the film removes some characters, and provides less information about others, it supplies new characters too. These are mostly Erica’s relatives – her brothers, her Aunt and Uncle – and add to the film’s comedy. While this bolsters Erica’s role, it mitigates her self-sufficiency. By contrast, Robert is given less of a back story in the film than the novel which details a previous name change so that he was able to receive an inheritance. The fact that in the film Robert accompanies Erica on the investigations she pursues alone in the novel impacts on her status as an independent woman. In the novel, Will is a menacing figure, who threatens Erica when she visits his isolated caravan alone. Will is altered to a more genial type in the film – he even gets dressed up and dances with Erica at the Grand Hotel. In addition, Robert’s own solo hunt for Will at a boarding house, gives Erica less opportunity to display her bravery.

The placing of a bickering couple at the film’s heart, in contrast to the novel, brought to mind another of Hitchcock’s’ films from a few years earlier. In The 39 Steps (1935) attention is expanded to encompass both Richard Hannay (Robert Donat) and Pamela (Madeline Carroll) in a significant divergence from John Buchan’s novel. This couple-focus is not exclusive to Hitchcock as Hollywood films especially privilege the couple. The mix of screwball and detective aspects was also in

The placing of a bickering couple at the film’s heart, in contrast to the novel, brought to mind another of Hitchcock’s’ films from a few years earlier. In The 39 Steps (1935) attention is expanded to encompass both Richard Hannay (Robert Donat) and Pamela (Madeline Carroll) in a significant divergence from John Buchan’s novel. This couple-focus is not exclusive to Hitchcock as Hollywood films especially privilege the couple. The mix of screwball and detective aspects was also in fashion at the time. The hugely popular The Thin Man (1934, WS Van Dyke) starring William Powell and Myrna Loy spawned many imitators and five sequels. This returns us to consideration of Young and Innocent’s genre. It deftly combines not just detective tropes and comedy elements, but aspects of male, as well as more traditional, melodrama. In Erica, it has a spirited, but at times vulnerable heroine, who interacts in interesting ways with the film’s elements of melodrama.

fashion at the time. The hugely popular The Thin Man (1934, WS Van Dyke) starring William Powell and Myrna Loy spawned many imitators and five sequels. This returns us to consideration of Young and Innocent’s genre. It deftly combines not just detective tropes and comedy elements, but aspects of male, as well as more traditional, melodrama. In Erica, it has a spirited, but at times vulnerable heroine, who interacts in interesting ways with the film’s elements of melodrama.

Do log in to add a comment or email me on sp761@kent.ac.uk and let me know that you’d like me to add your thoughts to the blog.