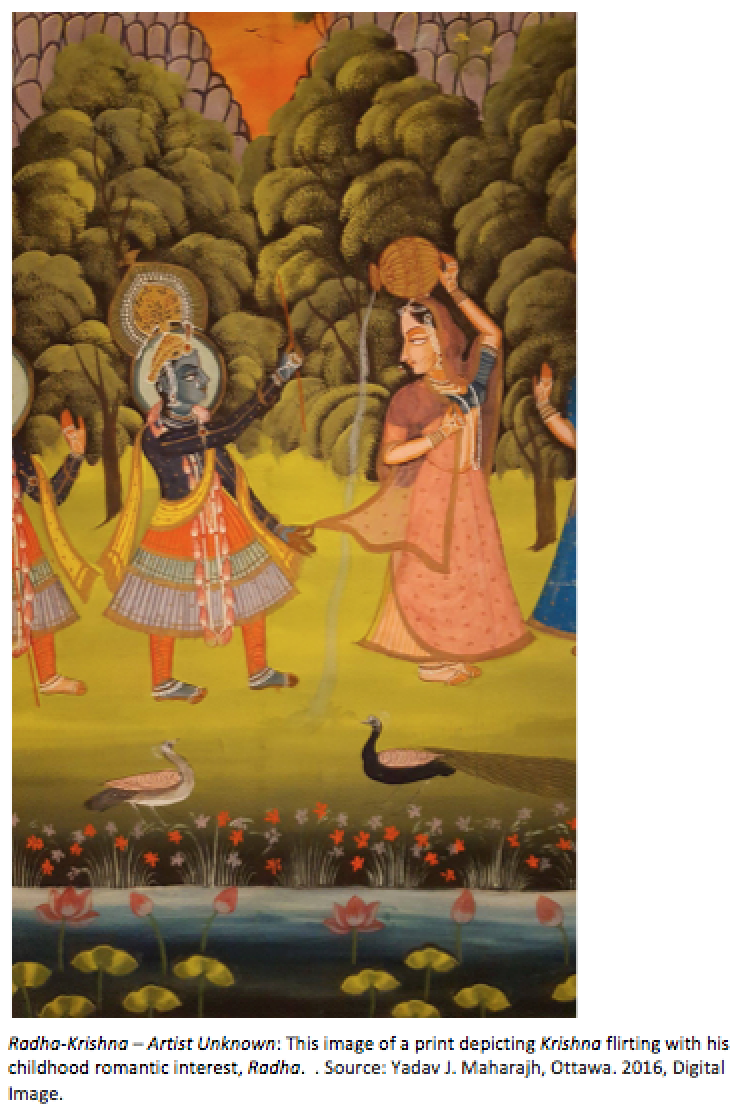

The ides of January coincides with the most auspicious time in the Hindu calendar known as Makar Sankranti (the northward solar ascendance into the constellation of Capricorn) and the beginning of the lunar month, Magh (14th January, 2017). Appropriately, Yadav Jagdeo Maharajh (an MA student at the University of Kent) explores the similarities in the myths of Krishna and Romulus.

Krishna is a well-known and widely celebrated figure belonging to Hindu and Vedic mythological traditions. He is an avatar of the God Vishnu and is himself a deified figure. The earliest literary works referring to him are the great epic “Mahabharata” within which is found the “Bhagavad-Gita” and the “Harivamsa”. This set of Sanskrit literature helps depict the story of Krishna from his birth to his death and apotheosis. It is through my knowledge and experience in studying the life of Krishna that I discovered a striking similarity to another well known mythological figure. He is one known more commonly to scholars of Roman history for being the founder of the eternal city; he is Romulus.

Though these two mythical figures have quite extensive bodies of work written about them that examine their significance as religious and political authorities, it is very rare that they are spoken of in the same sentence, at least in English academia. Some comparative works exist between ancient Indo and Greco-Roman mythological traditions, I have yet to find suitable academic analysis on the characters of Krishna and Romulus. Their stories and characters share so many similarities it would be irresponsible to not explore, beyond coincidence, as to why and how come they exist?

Krishna’s tale begins under similar circumstances to that of Romulus’. A demonic king named Kansa deposed his father, Ugrasena, to take rule of the kingdom of Mathura for himself. Kansa’s sister Devaki posed a threat to his rule should she bare progeny as it was prophesized that her offspring would kill him. Unable to slay her outright, Kansa had her and her husband Vasudev imprisoned with the intention to slay all children she may have. In prison Devaki would give birth eight times. Three of the eight would survive by the grace of the God Vishnu’s intervention. For the purposes of comparison to the myth of Romulus and Remus we need only concern ourselves with the final two survivors, Balarama and Krishna.

Balarama, Krishna’s elder brother, was miraculously transferred from Devaki’s womb to that of Rohini, Vasudev’s first wife. Krishna was born unto Devaki as the incarnation of Vishnu at which point the guards of their cell were rendered unconscious and Vasudev was set free from his chains. He was able to carry the baby Krishna secured in a basket across the river Jamuna and was placed under the care of a shepherd family in a nearby village. Later Balarama would also be placed in the care of the shepherd family. Some accounts describe Balarama and Krishna as twins, both being born to Rohini and then taken in by the shepherds. Together the boys would grow, learning in their adolescence of their uncle’s treachery and parents’ wrongful imprisonment. They would venture to Mathura together where they defeated Kansa, reinstated Ugrasena and freed Devaki and Vasudev. Later on in life the two would play the fundamental roles in founding the kingdom of Dwaraka.

Sounds familiar? Even in my extremely abridged re-telling above it may be evident to anyone initiated in Roman foundation mythology that the stories and characters of Romulus and Krishna are quite similar. Shared motifs are not uncommon in the comparison of ancient mythologies and indeed the stories of both characters share in other myths from additional cultures. Otto Ranke compared Krishna to Herakles. Kansa had once sent a female agent to poison the infant by nursing him, at which point Krishna severely bit his assailant foiling her attempt. This compares to Herakles foiling Hera’s attempt to poison him in the same fashion.

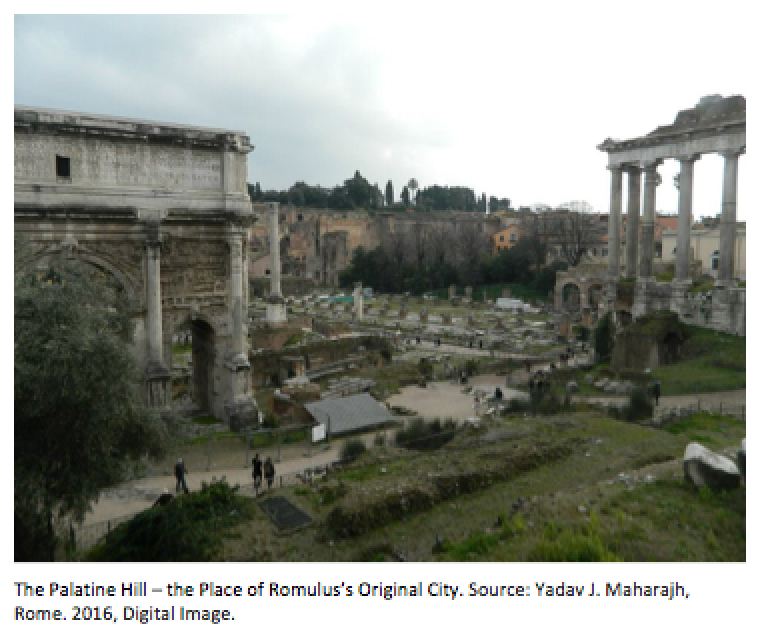

The tales of Romulus and Remus also share many similarities in motif and plot with the Greek myth of Tyro whose twins Nelius and Pelias grow up to kill their evil grandfather. It is evident then, that as for their characters, both traverse similar milestones such as founding and becoming rulers of their own cities, abducting their wives, and achieving military greatness. Their lives even come to comparable ends in that both ascend to the heavens and are deified upon their death.

There are of course inherent issues with the comparison that limit their parallel nature to that of coincidence. For example, there is the much-debated question in the Roman founding tradition of fratricide. Whereas Balarama is credited with a significant role in the Mahabharata, Remus’ purpose and fate remains a mystifying redundancy. Furthermore, the motif of being raised by the she-wolf is not mirrored in the tale of Krishna.

However, it is not unheard of in the Vedic tradition for animals to be anthropomorphized or for them to take significant roles in myths. Another issue with the comparison of ancient myth is the lack of a theory or traceable tradition indicating a common ancestry or source from which these myths may have evolved. The common aspects within the myths seem so prevalent globally that it is difficult to ascertain how these myths developed in separate cultures, at different periods and, yet, are so similar.

The interpretations of these myths, coupled with these traditions being orally transmitted prior to their earliest literary sources, render most comparisons between Romulus and Krishna speculative at best. This does however provide for the possibility and, I propose a necessity, for further research.

If we were able to derive Roman cultural traditions and practices to their earliest forms, it would help to better understand the mechanisms of cultural development and its societal function. The greatest difficulty I face providing grounds for further study in comparative research between ancient Indo and Greco-Roman cultures is my inability to find a comprehensive and widely accessible body of work on the subject. The primary vehicle by which I came across this necessity was my frustration with the overbearing linguistic focus of the Indo-European migration theory. I reason if the languages could evolve as they stretched across Asia and Europe than could this not also be indicative of a cultural migration?

I find the proof for this no more evident than in the overwhelming similarities between the mythological traditions, characters and motifs. Perhaps the comparisons between Romulus and Krishna extend more profoundly than their similar stories and characters. If we were to consider Romulus’ legacy as the eternal city then perhaps it would warrant looking back through eternity, at those cultures that cumulatively produced Rome.

Further Reading

The study of Indo-Vedic culture and its increasingly evident connection to Roman culture and tradition is quickly emerging as a prominent perspective for study. There have been, in recent times, greater allusions between the cultural practices and traditions of Ancient Rome with those of their Indo-Vedic predecessors as the study of Indo-European theories of linguistic and cultural migratory patterns expands.

One of the most prominent figures in the field is Georges Dumézil who wrote on Indo-European mythological and cultural connections in works like “Camillus: A Study of Indo-European Religion as Roman History” and “Mitra-Varuna: An Essay on the Two Indo-European Representations of Sovereignty”. For an interesting discussion of the Roman foundation myth by prominent Roman historians Mary Beard, Peter Wiseman and Tim Cornell be sure to check out “In Our Time: Romulus and Remus”. For further study on Krishna and Hindu Mythological traditions one may delve into “Encyclopedia of Hinduism” by Denise Cush, Catherine Robinson, and Michael York and “Krishna: A Sourcebook” by Edwin Francis Bryant.

The combined body of work in the fields touched upon by this blog is substantial in its own right with the potential for exponential growth.

Carandini, Andrea. Rome: Day One. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Leeming, David. “Oxford Companion to World Mythology – Oxford Reference.” 2006. Accessed October 17, 2016. http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195156690.001.0001/acref-9780195156690.

Mallory, J. P., and Douglas Q. Adams. Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. London: Fitzroy Dearborn, 1997.

Rank, Otto, Raglan, and Alan Dundes. In Quest of the Hero. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Rank, Otto, Gregory C. Richter, and E. James Lieberman. The Myth of the Birth of the Hero: A Psychological Exploration of Myth. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004.