Back in February of this year, Steve Hewlett’s interview of Stephen Hull, Editor-in-Chief of the Huffington Post UK, for the BBC’s Media Show created quite an online storm. It was hard to avoid the social media fallout, but in case you did, it revolved primarily around Mr Hull’s comments about the non-payment of the many bloggers who provide content for Huffington Post UK. Defending the media outlet’s position, Mr Hull controversially linked the refusal to pay non-staff writers in these terms: ‘If I was paying someone to write something because I want it to get advertising, that’s not a real authentic way of presenting copy. When somebody writes something for us, we know it’s real, we know they want to write it. It’s not been forced or paid for. I think that’s something to be proud of’.

Mr Hull’s equation of unpaid, voluntary contributions with an authenticity that he implies would be tainted by payment and its associated obligations to a media outlet’s advertisers caused quite a stir. Why on earth should objectivity be the province of the unpaid, we wondered? What will the long-term consequences of this reliance on unpaid writers for media content be for the future of journalism? Is the new media strangling the old? Is there really, as Mr Hull implies, any writing that is truly disinterested (whether you get paid for it or not)? And what do we do with the inconvenient truth that bloggers and journalists alike need to eat and pay rent?

At best, Mr Hull’s comments have been seen by his critics as naive. At worst, they have been cast as utterly parasitic: a devaluing of authorial labour under the guise of praise. But then again, is it any wonder that media outlets will rely on free copy in an ever expanding and cut-throat marketplace? Why should journalism be any more immune to austerity than any other profession, industry or service? And it’s surely the case, isn’t it, that a number of the bloggers who write for Huffington Post UK and other outlets aren’t doing so because they are being ‘forced’? Many, surely, choose such unpaid work in the hopes of future, paid career opportunities. But other writers might not care (much) about this. The reach and influence of the Huffington Post UK is such that it presents a formidable platform from which to articulate views and realities that the world needs to hear about. Sometimes getting such messages out matters more to the people who want to convey those messages than getting paid. Although I wonder how many would turn down offer of payment for their research and time if it were offered….?

As we move from an age of authors to the age of bloggers and social media enthusiasts, the questions about the value of authorial labour posed by Mr Hull’s comments are only ever going to become more pressing. And I, for one, am not optimistic about where the story is going to end. But in saying as much, I realise that I am adopting a position that is laden with irony.

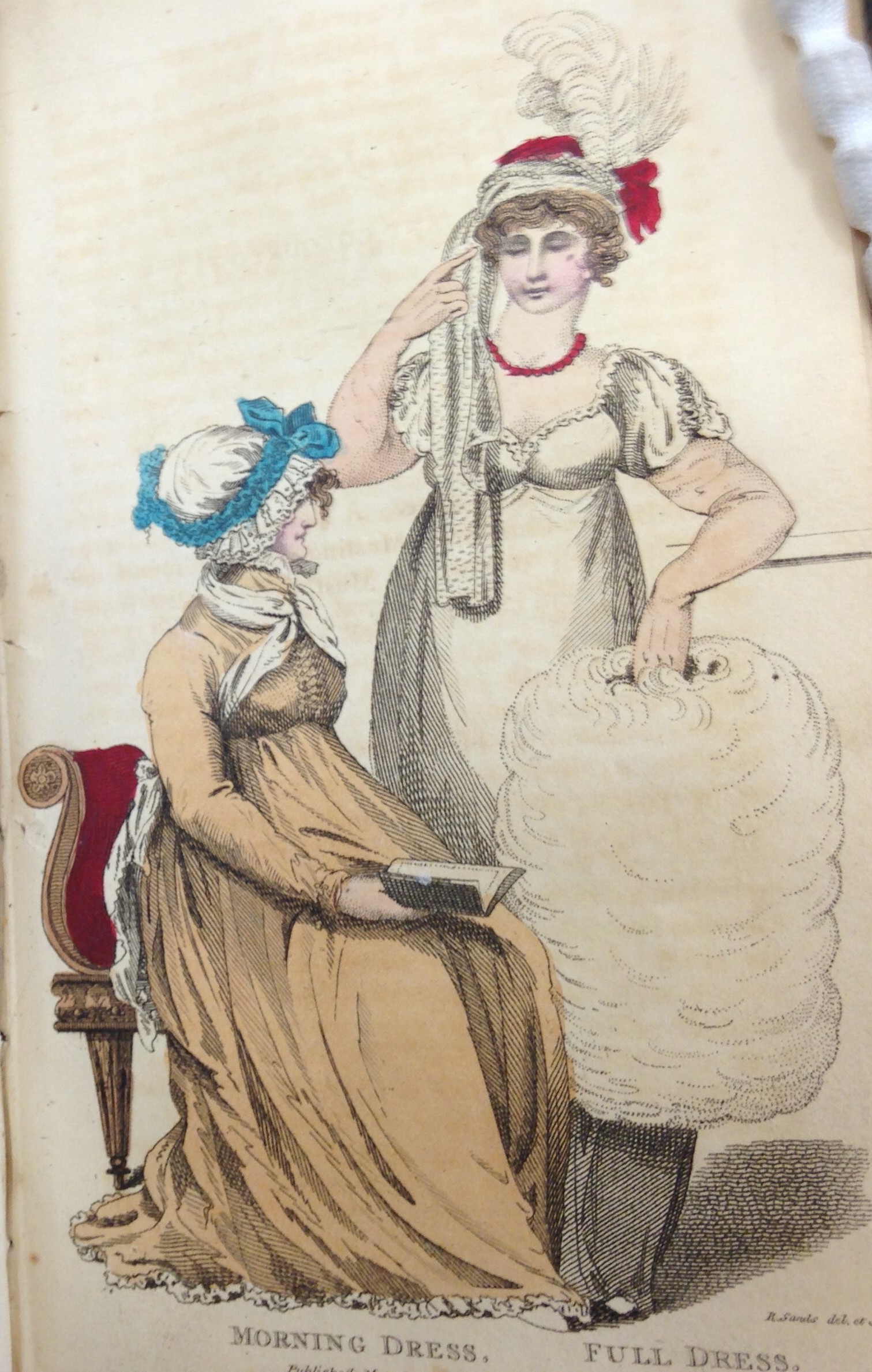

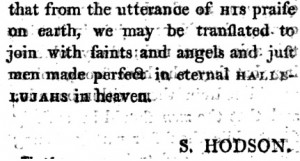

LM XX (1789). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

I am sat here writing this blog for free, just as I have written a magazine article and at least two other guest blog posts this month for no payment. Am I bitter about this? Not in the least. I do these things because I value the fact that these media opportunities open up our research to wider audiences than an academic book with its hefty price tag could garner. I do it because I love what I do and because I want to share that enthusiasm, to get feedback on work in progress, and (hopefully) to get better at it as a consequence. I do it, as Mr Hull suggests the Huffington Post UK‘s bloggers do, because I want to. But I firmly believe that I am no more objective in my blog posts than I have been in the odd bits of paid writing I have done over the years. And of course, I can do this voluntary writing because I have a full-time job that pays the bills and enables me to write for free. I thought the days of authorship being the preserve of only those who had leisure and means to do it had ended in the eighteenth century…

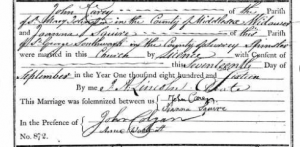

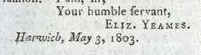

And herein lies the second irony. What makes me uneasy about Mr Hull’s comments is something that I have frequently and openly celebrated about the Lady’s Magazine: its creation of a community of volunteer reader-contributors who provided the magazine’s original content apparently free of charge. As I have argued at length elsewhere, one of the key reasons why the Lady’s Magazine has been so long neglected by historians and literary scholars is that its reliance on enthusiastic amateurs like John Webb, Elizabeth Yeames, and the hundreds of A.Z.’s, Anons and Nobodies whose copy fills its pages, means that it has been seen as insufficiently professional to be taken seriously [1].

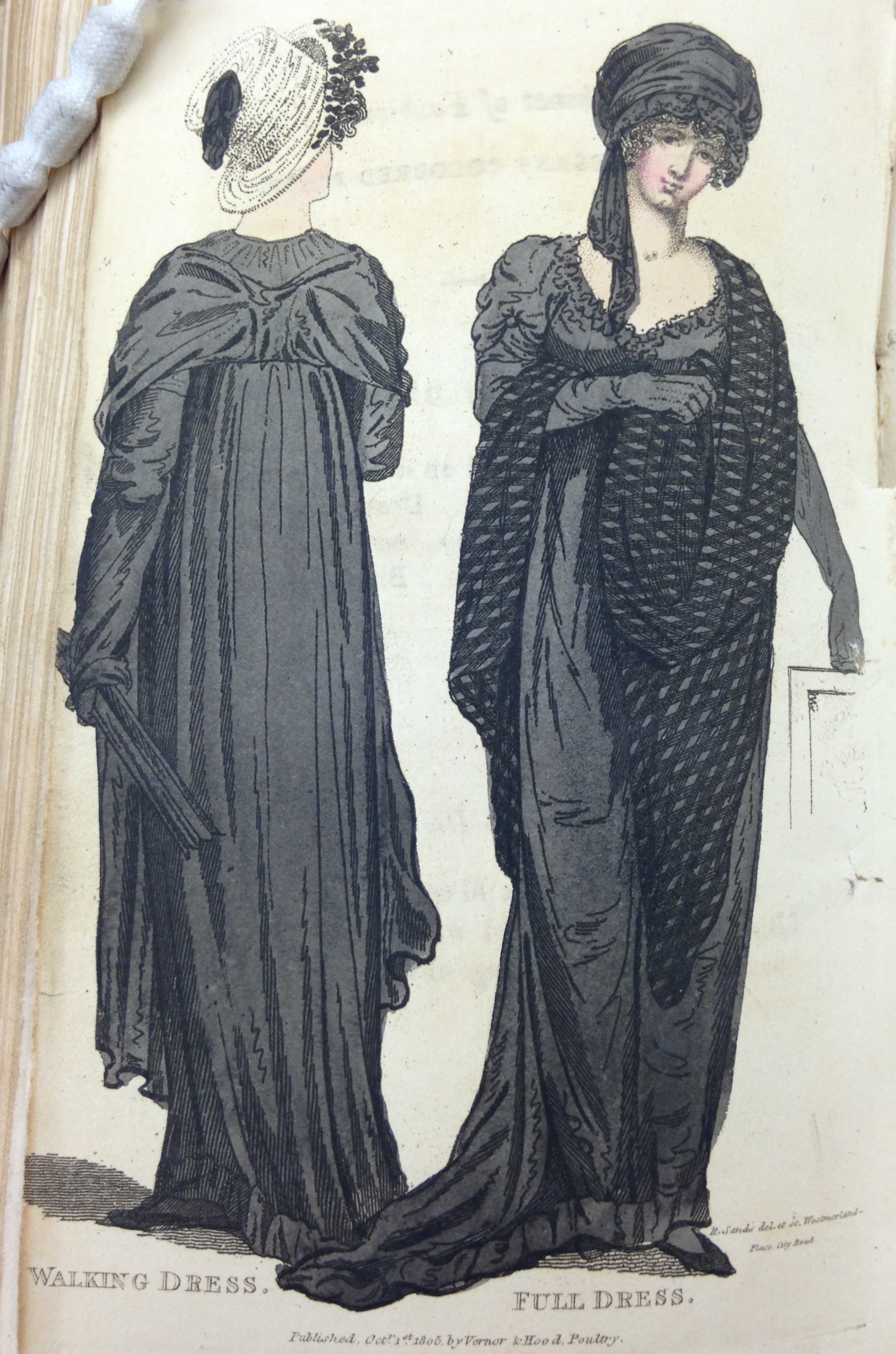

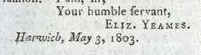

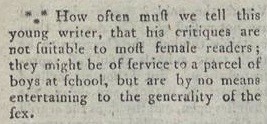

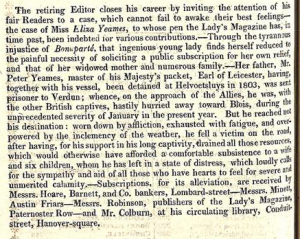

LM, XXXIV (May 1803): 253. © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

Why should this be the case? Why should we assume that just because the likes of Elizabeth Yeames might not have been paid for her work for the magazine that she didn’t take that work seriously? After all, as I pointed out in this blog post, the fact that she published in the Lady’s Magazine meant that she had a reach and influence that stretched over decades and continents. In the 1810s, she would likely have been read in greater numbers and been much more readily identifiable to readers than the anonymous author of Sense and Sensibility (1811). What does it matter if she was not paid for that work? Authorial success and literary value can’t be reduced to pounds, shillings and pence, can they? What if being read mattered more to her than being paid?

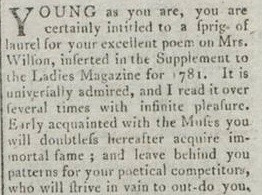

It’s a complex web of a problem if ever there was one, and it is one that the Lady’s Magazine itself was increasingly aware of as it moved into the nineteenth century. For the first decades of the magazine’s history, there is little sense that the non-payment of authors was anything other than a selling point for the publication. Write for us and you too can be read by thousands, is the implicit promise the editors made to their readers. Indeed, the magazine went to great lengths to ensure that potential contributors felt that publication in it was a prize, even if that prize involved no remuneration whatsoever or the kind of career beyond its pages secured by the likes of Mary Russell Mitford.

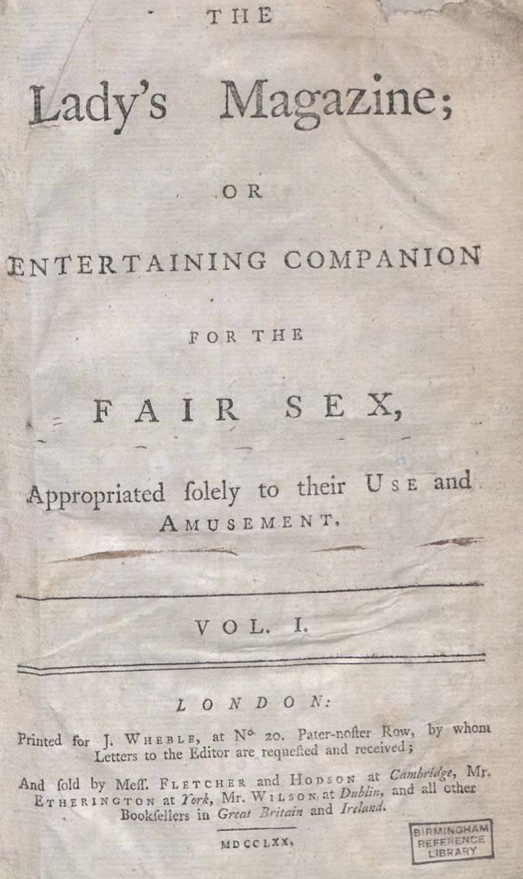

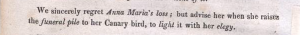

The magazine’s monthly columns acknowledging items submitted for publication are full of lavish praise for the best and most highly valued contributions, such as those of Henrietta R-, whom the editors acknowledged with the ‘greatest esteem, as well as gratitude’ in the August 1774 issue (no page). Equally, the magazine was rarely backwards in coming forwards with criticisms of what it conceived to be poorly conceived, written or inappropriately focused content. The magazine named and shamed many whose work it would not deign to publish, such as poor Anna Maria, whose poetic effusion on the death of a beloved pet was greeted in the September 1817 correspondents column with one of the editors’ most scathing rejections in its history: ‘We sincerely regret Anna Maria’s loss; but advise her when she raises the funeral pile to her Canary bird, to light it with her elegy‘ (no page). In the face of such public rejection, it is little wonder that ‘gaining a footing’ in the ‘inclosure’ of the magazine, in the form of being accepted for publication, felt like something worth attaining for many of the magazine’s authors, even if generated no income (LM 33 [May 1782]: 258).

LM XLVIII (Sept 1817). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

But a good number of the magazine’s contributors could ill afford to be cavalier about whether they got paid or not for their writing. Many, we know, most certainly did not write from a position of financial disinterest.

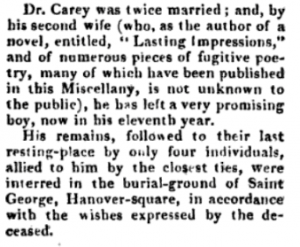

Mary Pilkington

Mary Pilkington, for instance, who undertook paid editorial work for Vernor and Hood’s Lady’s Magazine rival, The Lady’s Monthly Museum (1798-1828), also wrote various original articles and serials for the Robinson publication from 1809 onwards. As her polite but at times aggrieved correspondence with Vernor and Hood reveals, she absolutely relied on income from her journalism and other writing [2]. Between 1810 and 1825 an embarrassed Pilkington repeatedly called on the charity of the Royal Literary Fund for financially distressed authors with modest success, but insufficient to guarantee her long-term security [3]. Knowing what we do about Pilkington’s circumstances, it is quite clear that altruism can have played little part in this determinedly professional and financially straitened writer’s publication choices.

Such evidence about Lady’s Magazine contributors’ financial circumstances is hard to piece together. It relies first on us having an identifiable author to begin with and second on external evidence (journals, letters and, in the case of Pilkington, institutional archives) which is often very hard to track down or, in many cases, non-existent. In the absence of such documentation, authors’ dealings with and attitudes towards editors are hard to discern. Odd letters about contributors’ experience of publishing in the Lady’s Magazine exist but, at the moment, I can count the ones I have found and read so far on a couple of hands. Those parts of the relatively small archive around the magazine’s publishers, the various members of the Robinson family, that we have been able to consult so far offer little by way of illumination either. As Koenraad blogged here, the ledger of George Robinson’s copyright purchases has no information on material intended for publication in the magazine, a fact that seems to corroborate the longstanding assumption that no authors were paid for contributions to the Lady’s Magazine.

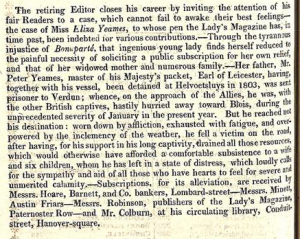

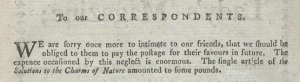

For the most part, then, we are left to glean the financial circumstances and motives of authors from their heavily mediated presence within the magazine’s columns. This is a hazardous enterprise, but nonetheless, offers glimmers of insight into how authors conceived of their work. Exhibit A in the author’s defence is the editors’ repeated refusal to pay postage for author contributions. For decades the editors implored readers that it could not ‘be deemed either humanity or generosity to involve us in such enormous expence’ as attended payment for unpaid postage (LM 33 [Oct 1782]: no page). And yet month after month contributors continued to send in articles in this manner, presumably hoping that the strength of their work would persuade the magazine to pay the postage costs even if no further remuneration was expected. But ultimately, without payment, without contracts, the magazine’s contributors had little bargaining power. In fact the only power they had over the magazine was to threaten to leave it if they felt its editors’ dealings with them were unfair. The frequent tailspins the magazine plunged into when successive instalments of popular fictions or essay series failed to arrive (post paid) are hardly surprising when authors were only under a moral, rather than financial, obligation to continue and complete them.

At the moment, however, I am amassing a body of evidence that strongly suggests that the magazine’s working relationship with its contributors was not static across its six decade long run. Indeed, from the 1810s, precisely at the point at which Pikington started writing from the periodical, there is evidence within the Lady’s Magazine that the tide of opinion was turning; that writers were expecting more from the magazine; and that the magazine itself recognised that its future was entirely dependent upon authors whom it could little afford to take from granted. Take, for instance, a notice published in the correspondents column of August 1811, in which the editor notes: ‘On the subject of “Payment,” in answer to A.B.’s inquiry, we have to observe, that, although the contributions to Magazines are usually gratuitous, we shall feel no objection to allow him a moderate remuneration for his productions, provided that we approve them’ (no page). That word ‘usually’ was surely a beacon a hope for many a writer looking not only to be published but hoping to be paid for their periodical essays.

LM XXXIV (Oct 1783): p. 320. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

Other hints surface in this decade that some of the Lady’s Magazine‘s contributors, at least, could expect payment for their efforts. The strange, but compelling serial, ‘The Author’s Portfolio’, which began publication in June 1814, is a wonderfully metafictional piece of writing about the hazards of life as a periodical author at the beginning of the new century. It is, in fact, one of several serial variations on this theme that appear in a very short space of time. The conceit of the ‘Author’s Portfolio’ is that its contents are the unpublished efforts of an unknown writer whose death is reported in its first instalment. The titular author takes lodgings in the house of a Mrs Stubbs, who takes the gentleman’s repeated assertions of the significant sums of money he carries around in his portfolio as a sign that he is a man of means, only to find out upon his death that he was insolvent and these papers were not banknotes, but manuscripts from which he hoped to secure future income. Succeeding where the author failed, on his death Mrs Stubbs takes the advice of a curate to send these unpublished papers to ‘”Messsrs Robinson, for publication in the “Lady’s Magazine”–not doubting that they would consent to pay a reasonable sum for the copyright’. The Robinsons acquiesce and the author’s funeral expenses are covered as consequence (LM 35 [June 1814]: 251).

The circumstances of the publication of ‘The Author’s Portfolio’ are likely an elaborate fiction. Nonetheless, it would seem odd to signal the magazine’s generosity in paying the copyright for works if this was something the magazine was not, at least on occasion, willing and able to do. This mention in the ‘Author’s Portfolio’, even with other evidence that I am piecing together from the magazine, is, sad to say, insufficient to suggest a sea change in attitudes to the payment of authors as the Lady’s Magazine moved into the nineteenth century. But coupled with what we know of the dire financial circumstances of some of its authors, it seems clear that at least some of the magazine’s non-staff writers were being paid in the 1810s, if not before.

More interesting still, perhaps, is the magazine’s increasing awareness in this decade that it had a moral and financial obligation to the men and women who provided its original content. In July 1814, for example, the magazine devoted its correspondents column to the plight of Elizabeth Yeames ‘to whose pen the Lady’s Magazine has, in time past, been indebted for various contributions’. At this time, Yeames who wrote for the magazine from the early 1800s through the 1810s (latterly under her married name of Mrs Robert Clabon) found herself ‘reduced to the painful necessity of soliciting a public subscription for her own relief, and that of her widowed mother and numerous family’, which included her widowed mother, her sister Catherine (another of the magazine’s contributors), a disabled brother and three other siblings. The magazine explained that Yeames’s father, Peter, master of ‘his Majesty’s packet, Earl of Leicester’ had, in 1803, the year she had first started writing for the magazine, fallen victim to ‘the tyrannous injustice of Bonaparte’ and been taken prisoner of war and died while being transported (no page.). The Robinson’s publishing house in Paternoster Row was one of three locations where subscriptions for Yeames were received.

LM XLV (July 1814): p. 320. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission

Now of course, had writing proved a more viable means of support, perhaps Yeames, like Pilkington (and numerous other writers of this period) might not have had recourse to charity. And I have no concrete evidence that the magazine paid Yeames for any of her contributions to it, although I suspect they at least latterly did. But what I find interesting in this transitional decade in the magazine’s history (the 1810s) is the editors increasing readiness to acknowledge the injustice and untenability of not financially supporting its writers.

Recognising such obligations undoubtedly presented problems for The Lady’s Magazine. It saw itself as mass media; it sought to keep its purchase price low to reach as many readers as possible; and given that it had a seemingly endless supply of people willing to write for nothing why should it pay anyone at all? But the magazine had to move with the times. And as part of its constant efforts to position itself strongly within an increasingly professionalised periodical marketplace, it had to reassess the way that it valued the authorial labours of its contributors.

That nearly two hundred years after the Lady’s Magazine started to talk more openly with its readers about payment for copy and to reflect publicly on its pecuniary and moral obligations to its writers similar debates about the value of authorial labour have resurfaced so loudly should give us pause for thought. New media might have a lot to learn from the new media of old.

Notes

[1] Jennie Batchelor, ‘”Connections which are of service . . . in a more advanced age”: The Lady’s Magazine, Community, and Women’s Literary Histories’, Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 30 (2011): 245-267.

[2] Some of Mary Pilkington’s letters to Vernor and Hood have been preserved in volume 3 of ‘Original Letters, Collected by William Upcott of the London Institution. Distinguished Women’, 4 vols. British Library. Add, Ms 78688.

[3] Archives of the Royal Literary Fund: 1790-1918, 145 reels (London: World Microfilms Publications, 1981-4), reel 7, case 256.

Dr Jennie Batchelor

School of English

University of Kent.

The Stitch Off continues apace, with new items arriving each week and comments from visitors pouring in to tell us how much they admire and are inspired by the wonderful exhibition of our followers’ work on display at Chawton House Library, as part of their ‘Emma at 200′ exhibition. I have said it before, but honestly, the Stitch Off is one of the most enjoyable projects I have ever been, and likely ever will be, involved in in my working life. So you can imagine how I felt when I was asked by the Editor of The Quilter if I would write something about how it all came about for their summer 2016 issue (number 147). I received my hard copy of the magazine last week, and it now takes pride of place on my coffee table at work. If you would like to read the article, you can find it here.

The Stitch Off continues apace, with new items arriving each week and comments from visitors pouring in to tell us how much they admire and are inspired by the wonderful exhibition of our followers’ work on display at Chawton House Library, as part of their ‘Emma at 200′ exhibition. I have said it before, but honestly, the Stitch Off is one of the most enjoyable projects I have ever been, and likely ever will be, involved in in my working life. So you can imagine how I felt when I was asked by the Editor of The Quilter if I would write something about how it all came about for their summer 2016 issue (number 147). I received my hard copy of the magazine last week, and it now takes pride of place on my coffee table at work. If you would like to read the article, you can find it here.