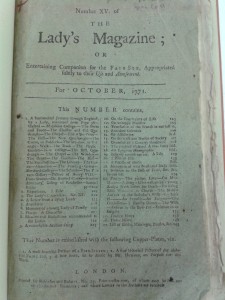

One of the great pleasures and well as challenges of working on the Lady’s Magazine and other miscellanies of its day is the extraordinary breadth of content with which you are confronted. My literary training in the period has equipped me with ways of, and contexts in which, to read eighteenth- and early-nineteenth century novels, tales, poems, essays, criminal biographies, reviews, travel writing, news and other, principally prose genres too numerous to mention. My expertise is clearly much stronger in some areas than others, but I’m not going to reveal the chink in my academic armour and tell you which I’m not so hot on. Oh well, as it’s just us, I’ll tell you that basically anything to do with maths or what we could call the sciences makes me sprint for the aspirin jar.

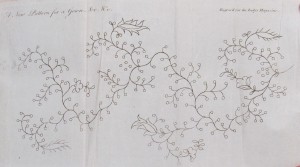

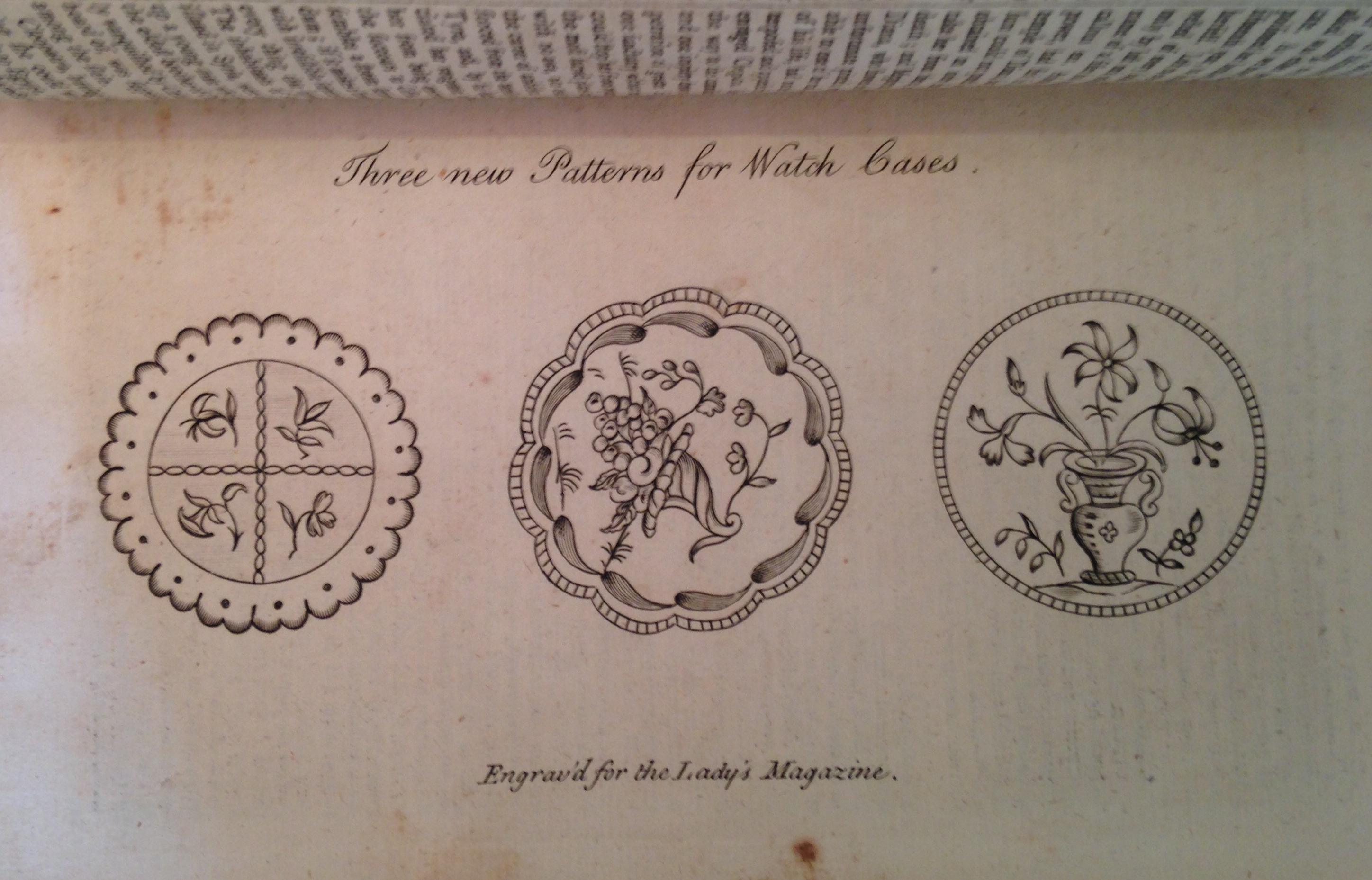

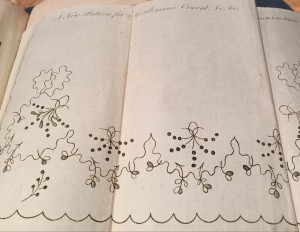

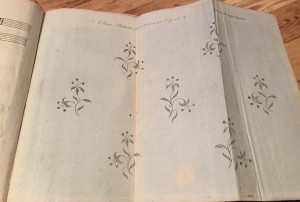

My life-long fascination with material culture means I have strategies for reading fashion plates, reports and embroidery patterns, too, although despite my best efforts, I know that I will only ever be an amateur art or textile historian. I lack the knowledge to situate and fully grasp the context for the magazine’s sheet music, but years of dabbling in lots of musical instruments, none of which I play very well, means I can sight read and hum or sing the tunes I come across.

The real headache for me is the foreign language material in the magazine, of which there is a small but significant amount, most of which is in French. My French is just not good enough to be competent in reading these articles in a scholarly context. (This is another of the million reasons why Koenraad is such an asset to the project.)

Often the foreign language material is translated in the magazine, however, so I can at least usually read it in English. But I am always aware that to do so is potentially to limit meaning and erase context. The more I read the magazine, whether I am looking at Parisian fashion plates, or reading memoirs, or essays on education translated from French or German, the more I am interested in how this self-avowedly British magazine is, like so much eighteenth-century print culture, produced in a much more complex and rich European context of intellectual exchange and debate than we Anglophone scholars often acknowledge and that we overlook to our cost.

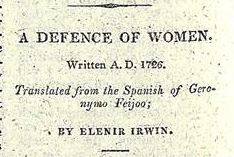

LM XLI (Nov. 1810): 508. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

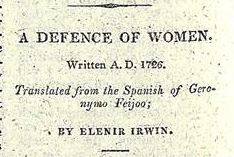

This is an issue that was brought home to me very forcefully in recent weeks when I was spending more time with the 1810 and 1811 issues of the magazine, which featured from November 1810 to August 1811 a serial and apparently unabridged translation of a work from the Spanish under the following title: A Defence of Women. Written A. D. 1726. Translated from the Spanish of Geronymo Feijoo. The translator’s name is given as Elenir Irwin, a name which, to my knowledge, does not appear again in the magazine and whose identity, if indeed this is a legal name rather than a pseudonym, I have not yet been able to confirm.

The fact that the magazine was publishing translated Spanish essays and excerpts did not surprise me. Although French and German are the most common languages of non-English source-texts in the magazine, Spanish material appears from time to time. In 1810, however, the magazine excels itself in an interest in all things Spanish. In March 1810, for instance, it publishes a biography of King Ferdinand VII, and throughout the year extracts appear from texts including Jean-François Bourgoing’s Travels in Spain (an English translation of which had been published by the Robinsons in 1789), Robert Semple’s Second Journey in Spain (1809) and Alexandre de Laborde’s A View of Spain (also 1809). What did surprise me was the content of Feijoo’s extraordinary work and the fact that, in my ignorance, I had never heard of him before.

Portrait of Feijoo y Montenegro by Juan Bernabé Palomino.

A quick search pulled up an English and a more detailed Spanish Wikipedia page for Benito Jerónimo Feijoo (1676-1764), a Benedictine monk who wrote hugely engaging and popular learned, multi-volume collections of essays, including the Teatro crítico universal de Errores communes (1726–1740) from which ‘Defence of Women’ (Defensa de las Mujeres) is taken. From the opening lines, I was hooked by the compelling modernity of Feijoo’s words, at least as they were translated into English:

While I enter with alacrity upon the defence of the female sex, I am aware how arduous is the undertaking: I am not merely preparing to encounter the prejudices of the vulgar, but in attempting a universal defence of one sex, I am in danger of a general censure from the other; as there are few men who do not please themselves in asserting their superiority in the scale of being; and many of them extend their contempt for women so far as to deny them almost every excellence. They think their minds peculiarly prone to vice, and their bodies subject to disease.

The point on which these objectors argue with the least reason, is the narrow limit of the female understanding; and therefore after I shall have given a concise refutation of their other attacks, I mean to speak more largely upon the capability of women to acquire the most abstruse sciences, and to ascend to the sublimest speculations. (LM XLI [Nov. 1810]: 508-9)

The text proceeds with a debunking of various, spurious philosophical, medical and cultural myths of gender and reflections on the achievements of a catalogue of European female worthies in its bid to assert women’s moral, physiological, spiritual and intellectual abilities. As it does so, the text betrays some hallmarks of its time, but the abiding sense I had in reading this extraordinary work was shock was that this was a text from the 1720s, authored by a Spanish monk, and that I had never heard of it. Could Feijoo have ever imagined that his essay would be being read by British women in English nearly 90 years after its first publication in Spanish?

I tried to research the reception history of the text and track down British translations from which the Lady’s Magazine translation could have been drawn. My initial searches turned up a couple of prior British translations, one of which I located easily on ECCO, the other I couldn’t initially find (but later did). Neither of these translations matched that in the magazine. And then I had the extreme good fortune to be put in touch with Dr Mónica Bolufer Peruga in the Department of Modern History at the Universidad de Valencia, and who has published a wonderful essay on ‘Rational Equality in the Early Spanish Enlightenment’, which includes a wonderful account of Feijoo’s Defensa in a broader European context in Sarah Knott and Barbara Taylor’s indispensable, Women, Gender and Enlightenment (2005) [1].

Monica alerted me to the fact that there are three known English translations of Feijoo’s Defensa in the eighteenth century: An Essay on Woman, or Physiological and Historical Defence of the Fair Sex. Translated from the Spanish of el Theatro Crítico (London: W. Bingley, c. 1765); Three Essays or Discourses on the Following Subjects. A Defence or Vindication of the Women. Church Music. A Comparison between Antient and Modern Music. Translated from the Spanish of Feyjoo by a Gentleman (Londor: T. Becket 1778); An Essay on the Learning, Genius and Abilities of the Fair-Sex, Proving them to be not Inferior to Man, from a Variety of Examples extracted from Ancient and Modern History. Translated from the Spanish of El Theatro Crítico (London: T. Steel 1774). The Lady’s Magazine translation matches none of these. And while this doesn’t definitely prove the translation is original to the periodical, it does suggest that Elenir Irwin might well have existed and that she may have been able to translate – and it is an eloquent translation – from Spanish into English, or perhaps Feijoo came to her via a 1755 French translation that neither Dr Bolufer nor I have been able to locate.

In a sense, though, the originality or otherwise of the translation is the least interesting thing about it. Its contents are provocative and rhetorically charged yet measured in its learned campaign to persuade readers that ‘the excellencies of men cannot be denied to women’ (LM XLI [Dec 1810]: 531). There are hints of Mary Astell’s Serious Proposal (1694-97) and Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) and there is a lot more to say about the text’s argument than I have space to say here.

But to leave off for now, it was a shade of Jane Austen in the translation of Feijoo’s ‘Defence’ that almost stopped me in my tracks. In Chapter IX, Feijoo introduces an ‘allegory’ from the Sicilian Carducio (Vincenzo Carducci) in his ‘dialogues on painting’ about a man and a lion discoursing on the relative merits of their species. Feijoo interprets the ‘fable’ of the allegory in the context of the woman question and formulates it thus: ‘Men were the writers of those books in which the understanding of women is stigmatized as inferior to ours. If women had penned them, we ourselves might have been brought low.’ (LM XLI [Supp 1810]: 595)

Had Jane Austen read this when just a few years letter she too would put such similar words in the mouth of Anne Elliot? I wish I could say I knew. But I don’t. And as the very often (though not always) right Anne concludes, we really can’t allow books to ‘prove anything’ after all. But the rich, transnationally influenced and culturally complex contents of the Lady’s Magazine surely have lots and lots to teach us.

Dr Jennie Batchelor

School of English

University of Kent

Notes

[1] Mónica Bolufer Peruga, ‘”Neither Male, Nor Female”: Rational Equality in the Early Spanish Enlightenment’, in Women, Gender, and Enlightenment, ed. Sarah Knott and Barbara Taylor (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), pp. 389-409.

Not really. If you are willing to have your work on display and don’t mind it being handled – it will be on a table, not behind glass – then all you need do is send it to us and we will return it to you when the exhibition ends. It will take pride of place on a display in the Oak Room of Chawton House Library, which will be devoted to the subject of female accomplishments (music, painting and needlework) for the exhibition’s duration. We’d also love it if you could send pictures to us via Twitter or Facebook along the way so we can share your work and experiences with others.

Not really. If you are willing to have your work on display and don’t mind it being handled – it will be on a table, not behind glass – then all you need do is send it to us and we will return it to you when the exhibition ends. It will take pride of place on a display in the Oak Room of Chawton House Library, which will be devoted to the subject of female accomplishments (music, painting and needlework) for the exhibition’s duration. We’d also love it if you could send pictures to us via Twitter or Facebook along the way so we can share your work and experiences with others.