One of the questions we are often asked about the Lady’s Magazine (1770-1832) is regarding the identities of the magazine’s thousands of anonymous and pseudonymous writers who were often longtime contributors. Koenraad, Jennie and I have all written about some of the methodologies we use, problems we encounter and attributions we have made in various blog posts regarding the identity of these elusive authors. While my role on the project is focused on the examination and analysis of content, I often become intrigued (some might say obsessed) with the question of the individual behind the mask. In such instances, our team’s collaborative efforts are at once essential and particularly fruitful.

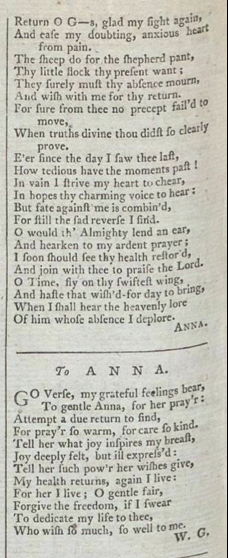

LM IX (March 1778): 148. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

‘R’, a prolific contributor of tales and translations, was a particularly intriguing puzzle in terms of identification for a number of reasons. First, the number of contributions by ‘R’ was enormous and varied and the simple letter ‘R’ could be used by any number of different contributors. Additionally, ‘R’ was signed variously ‘R’, ‘R.’ and ‘R—’, making it difficult to pin down which contributions were from the individual we sought and not another ‘R’. Finally, the initial ‘R’ and its voluminous contributions raised the potential question of a link to magazine’s publishers, the Robinson family, and one of its initial publishers, J. Roberts. The various ‘R’ signatures to the tales and translations are likely distinct from the ‘R’ signatures to a serial feature in the magazine also appearing in the early to mid-1770s, ‘The Friend to the Fair Sex.’ While the ‘R’ who contributed tales and translations sometimes self-identifies as a ‘lady’, readers tended to address the ‘R’ author of ‘The Friend to the Fair Sex’ as a male, in part because the serial often berated women. While this isn’t proof that the signature was in use by multiple contributors, it does indicate that there were at least two distinct writers using the initial in the first decades of the magazine.

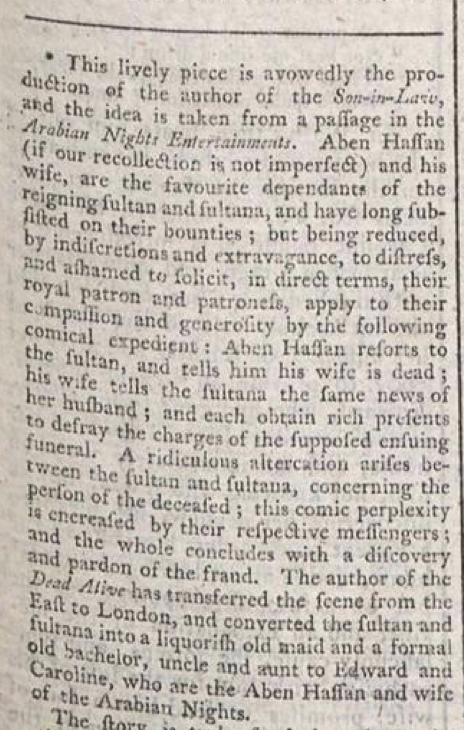

LM IX [March 1778]. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

The search began in earnest after Koenraad located a note by E. W. Pitcher to the

Literary Research Newsletter Vol. 5, No. 3 (summer 1980). Pitcher contributed ‘The Miscellaneous Periodical Works and Translations of Miss R. Roberts’ that attributes the items signed “R-” to this obscure magazine writer of the late eighteenth century. In the article, Pitcher points out that some of serials signed ‘R’ also used pseudonyms such as ‘Georgiana’ in different installments and were thus perhaps ‘translations of young ladies under her tutorship’, pointing towards Miss Roberts’ potential role as a teacher whose translations for the magazine were at times composites of her work and that of her students (Pitcher, 127). Miss R. Roberts, Pitcher further notes, was the sister of Dr. Roberts, who was the High Master of St. Paul’s School. Using this as our starting point, the hunt began.

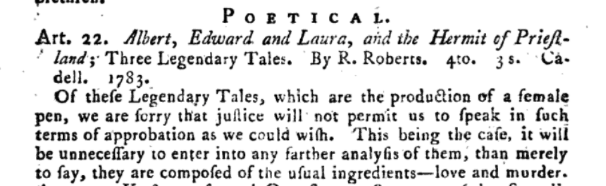

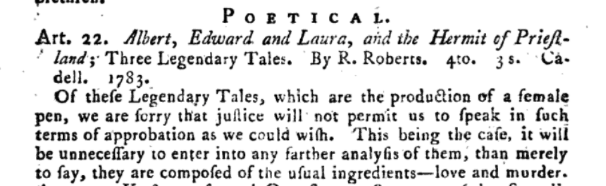

There is, in fact, an ONDB entry for ‘Roberts, R.’, that lists the elusive contributor as a translator and sermon writer, detailing information about her family in Gloucester and mentions her brother, Dr. Roberts, naming him as Richard (another ‘R’) and listed a host of her works; primarily translations. Roberts’ publications include: Select Moral Tales (Gloucester: 1763), a translation of four tales from Jean François Marmontel’s Contes moraux; Sermons Written by a Lady, the Translatress of Four Select Tales from Marmontel (1770); Elements of the History of France (1771), an abridged translation of Claude-François-Xavier Millot’s Élemens de l’histoire de France; Peruvian Letters — a translation of Mme Françoise de Graffigny’s Lettres d’une péruvienne (2 vols., 1747), The triumph of truth; or memoirs of M. De La Villette (T. Cadell, 1775); Malcolm (1779) an unstaged blank-verse tragedy; and Albert, Edward, and Laura, and the Hermit of Priestland; Three Legendary Tales (1783).

The Monthly Review; or, Literary Journal LXIX (July-Dec): 342.

Roberts’ most significant work was probably the translation of Graffigny’s letters, to which she added a third volume consisting of nine letters. The attribution of the translation to Miss Roberts derives from a letter by Frances Brooke, a contemporary (and rival) translator and periodicalist who was much better known than Roberts. Marijn S. Kaplan’s edition Translations and Continuations: Ricoboni and Brooke, Graffigny and Roberts provides details of Roberts’ translations and her connection to Frances Brooke, with whom Roberts shared a publisher and whose son Jack attend St. Paul’s School, where Roberts’ brother was High Master (Kaplan, xi-xii).

GM, 58 (Jan 1788): 85

While the ONDB entry suggests that Roberts spent most of her life in Gloucester, noting the family link to Hannah More (via her nieces Mary and Margaret, daughters of her brother William) and her connection to Dr. Hawkesworth, Roberts’ first name and any details of her own life were absent. Using the information in the ONDB I began searching for her brother and family members. Eventually I uncovered the family’s genealogy records on ancestry.co.uk and although I found Richard, William, and other siblings in the records of St. Philip and St. Jacob’s, Bristol, there was no female ‘R’ listed in the available parish records. Yet the ONDB had offered a very specific death date of 14 January 1788 so, using that date and the last name Roberts, I worked backwards in my search, restarting with death rather than birth.

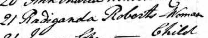

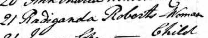

Finally, success! I located the burial record for a ‘Radiganda Roberts’ in Surrey, Southwark borough, in the parish of St. Mary, Newington, buried on 21 January 1788. The enigmatic Miss Roberts was no Rachel or Rebecca, but something much more unusual altogether.

Finally, success! I located the burial record for a ‘Radiganda Roberts’ in Surrey, Southwark borough, in the parish of St. Mary, Newington, buried on 21 January 1788. The enigmatic Miss Roberts was no Rachel or Rebecca, but something much more unusual altogether.

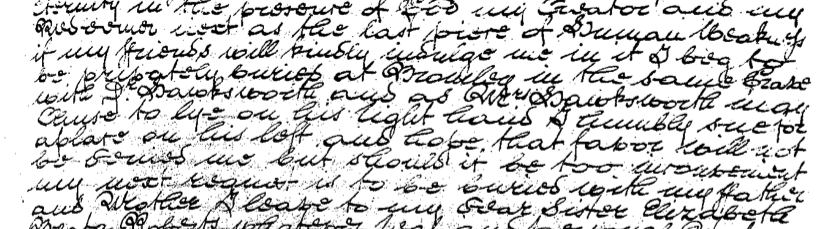

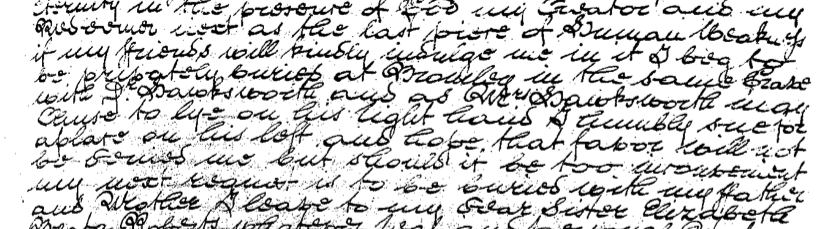

I cast my net further, moving onto various records including the National Archives website. Another success: the will of ‘Radagunda Roberts’ – and what a will it was. It established the identity of Miss Roberts as Radagunda, who died in Southwark listed in the parish records as ‘Radiganda’. Additionally, it established a very firm and odd link to Dr Hawkesworth that was hinted at in the description of her translation The triumph of truth; or memoirs of M. De La Villette (T. Cadell, 1775) as ‘undertaken at the request of the late Dr Hawkesworth, who revised and corrected the translation’ (Daily Advertiser, 7 August 1775).

Image © The National Archives, not to be reproduced without permission.

The will states ‘if my friends will kindly indulge me in it I beg to be privately buried at Bromley in the same grave with Dr. Hawkesworth and as Mrs. Hawkesworth may chuse to lye on his right hand I humbly sue for a place on his left and hope that favor will not be denied me but should it be too inconvenient my next request is to be buried with my father and mother’. Roberts’ request to lie on Dr Hawkesworth’s left was not granted and she was buried with her family. The intriguing request, hardly conventional for an unmarried and religious woman of the eighteenth century, points to a close relationship with John Hawkesworth (1715-1773), the celebrated translator of Telemachus (trans. 1768) whose edition of Cook’s Voyages was so largely criticised it was said to have hastened his death. Roberts’ copy of Hawkesworth’s Telemachus is singled out in her will; Roberts requests that her nephew, Alfred William Roberts, single out the book and preserve it along with her inkstand.

The will’s usual bequests to family members demonstrate her closeness to her nieces and clarifies that she did not, as the ONDB suggests, spend her life in Gloucester but rather lived with her brother Dr Richard Roberts and his wife in London. It is likely that she moved to London after the publication of her 1763 translation of Marmontel, which was published in Gloucester, and before the publication of Sermons Written by a Lady, the Translatress of Four Select Tales from Marmontel, which was published in London in 1770.

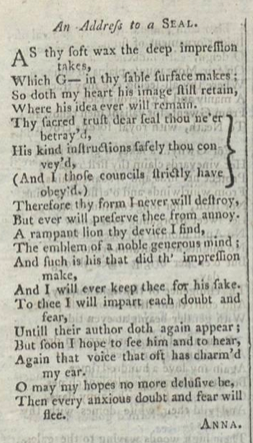

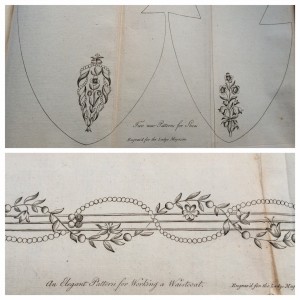

LM VII [Sept 1777]: 484. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

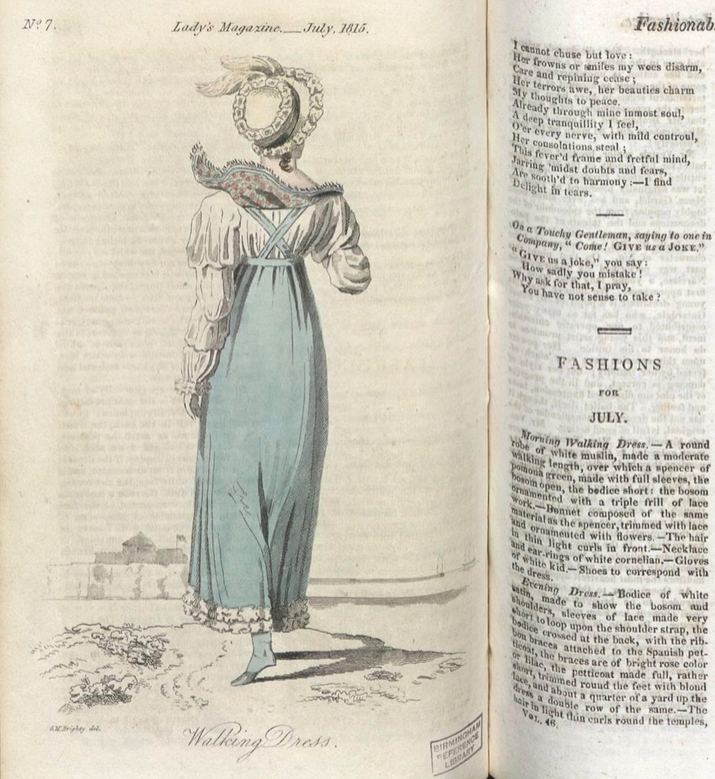

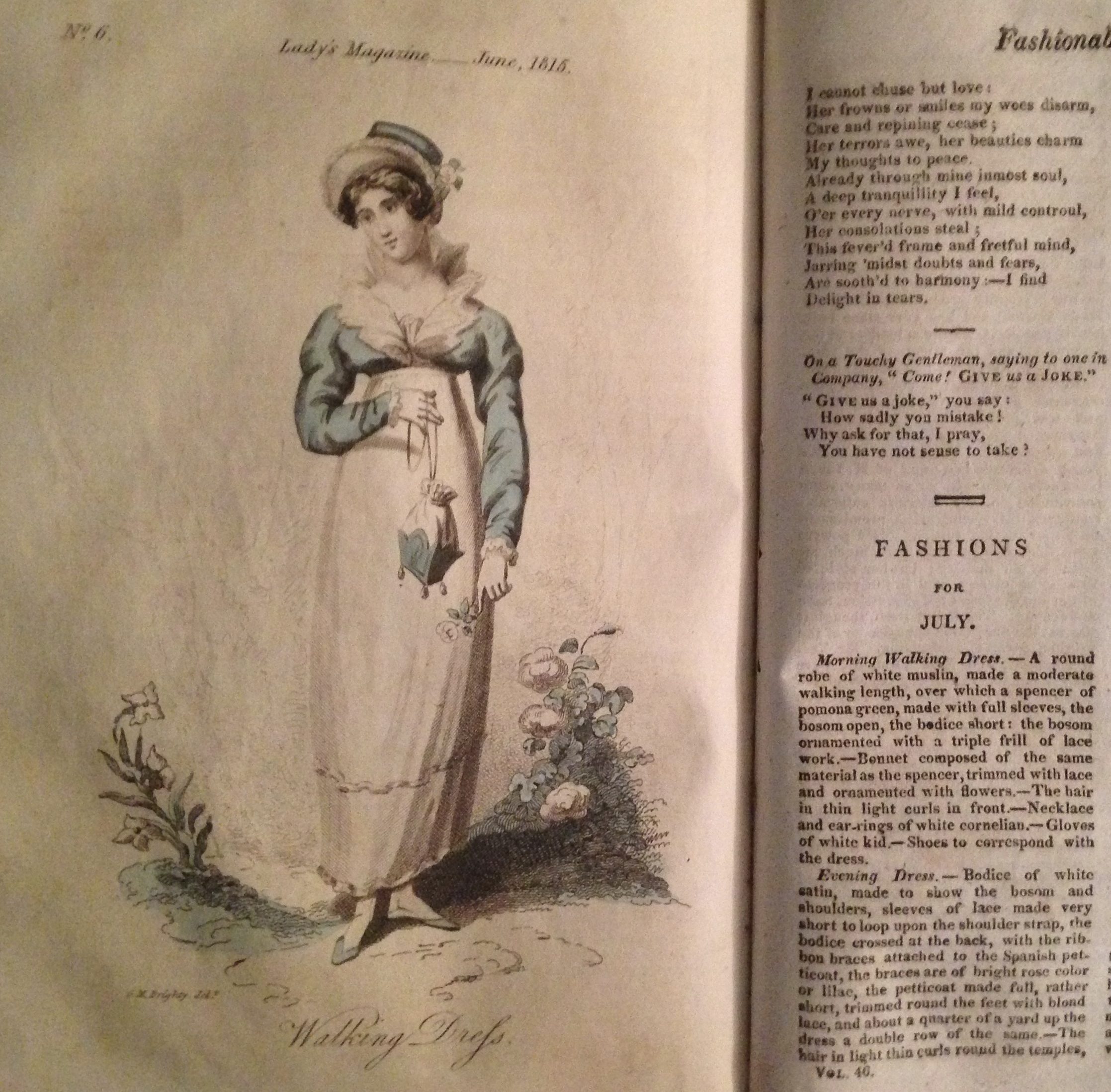

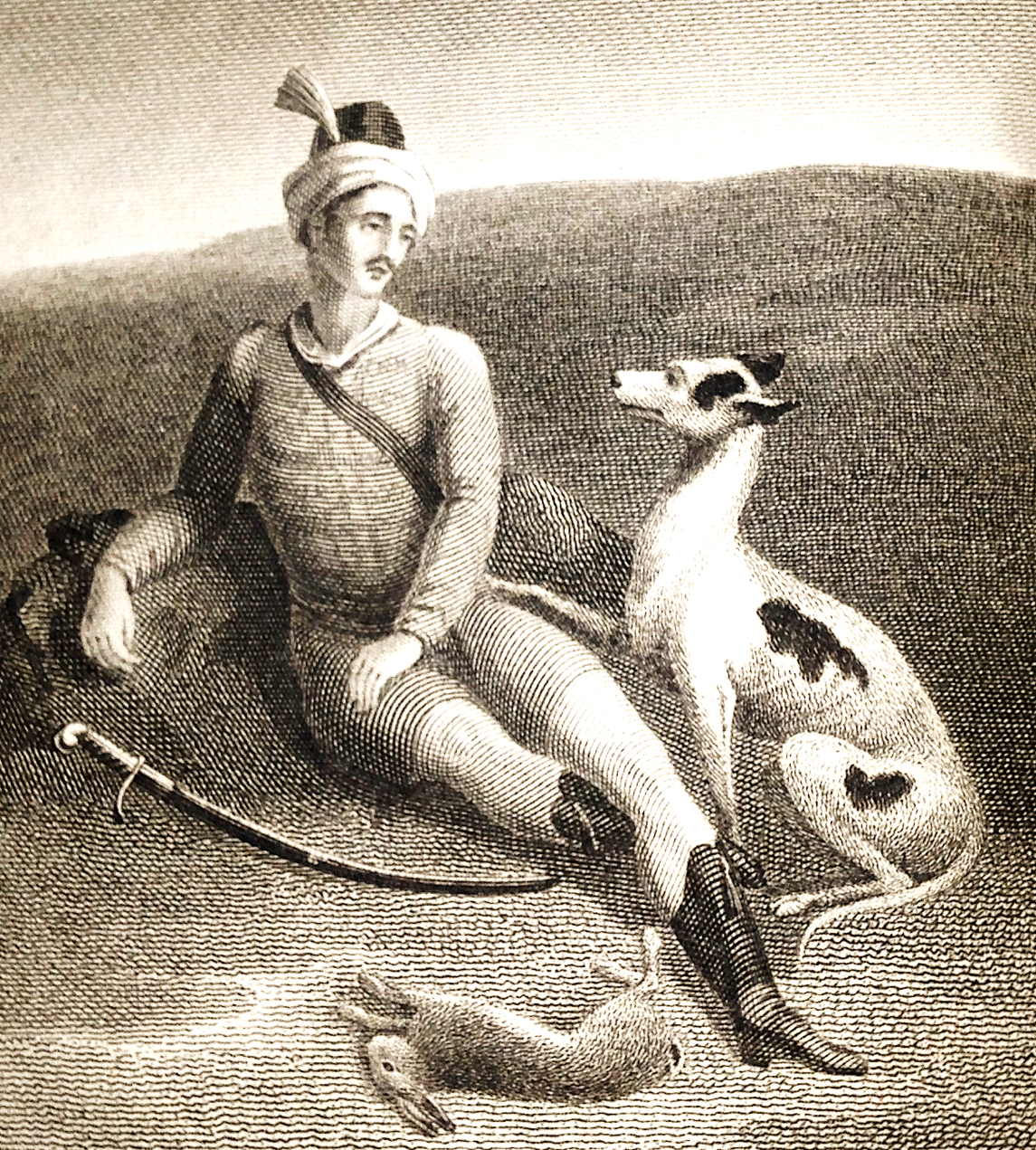

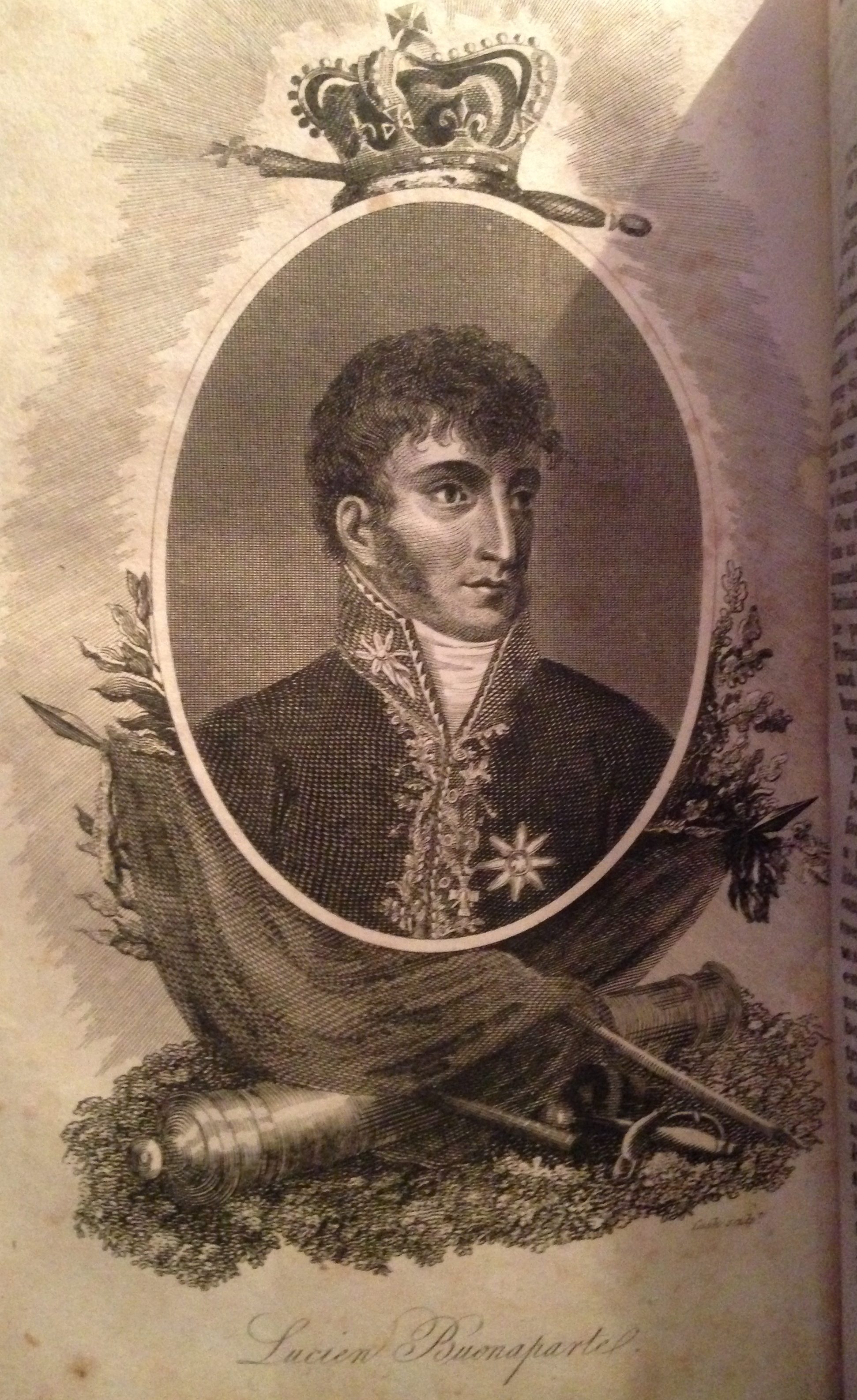

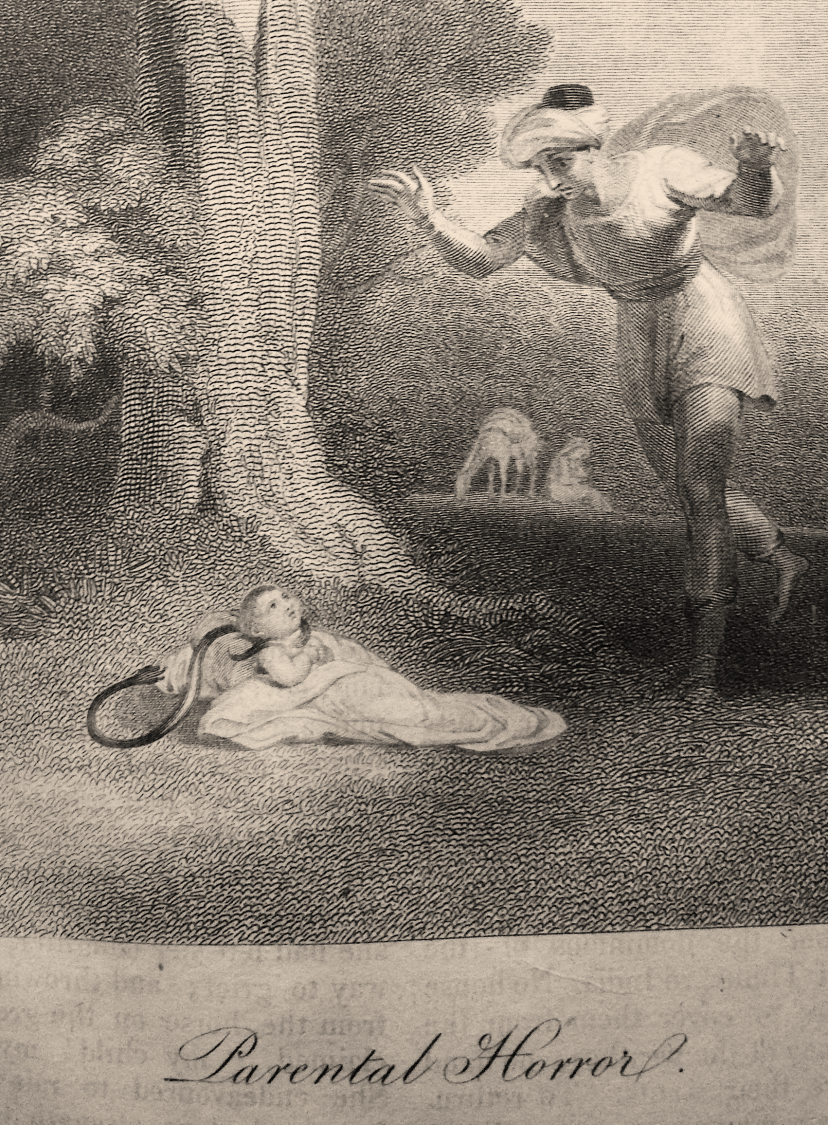

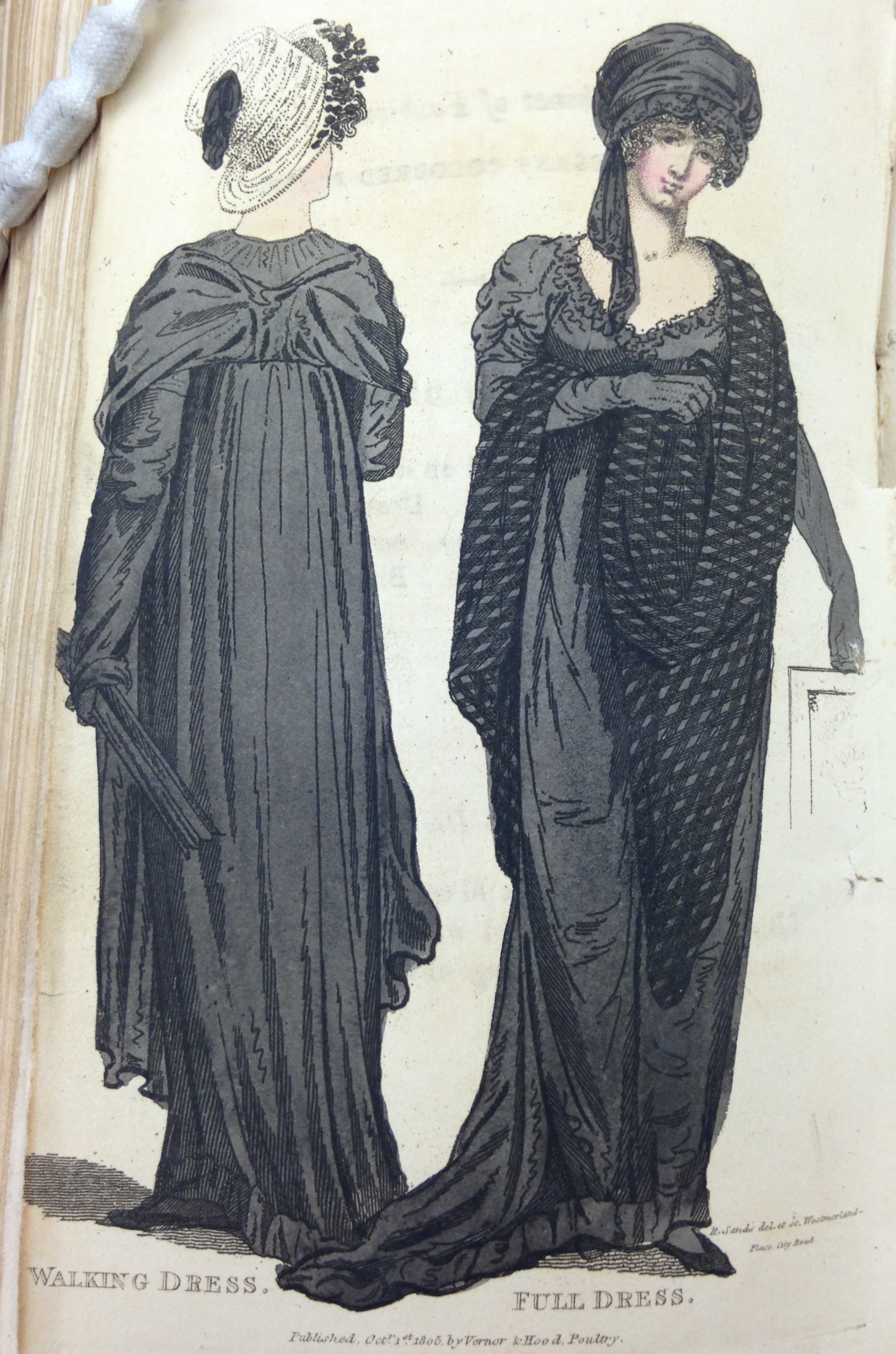

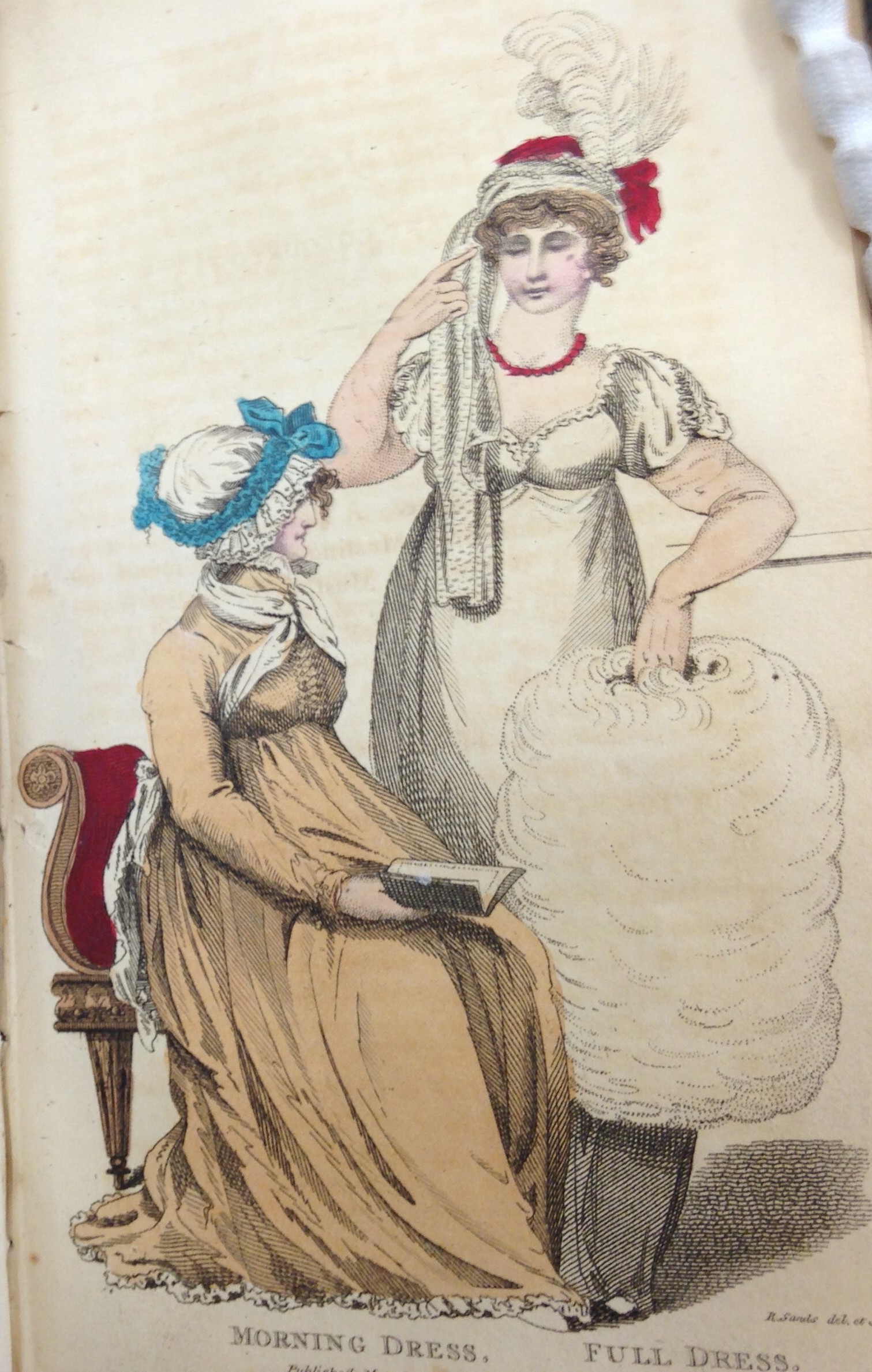

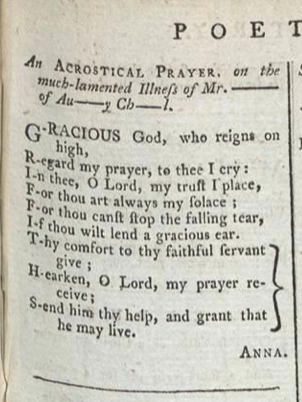

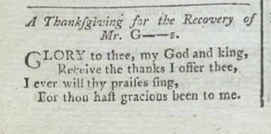

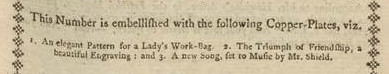

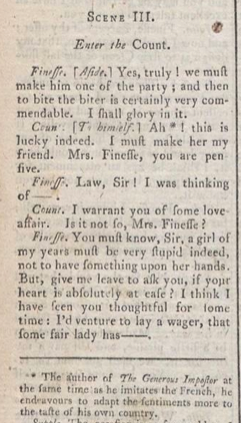

Her contributions to the

Lady’s Magazine include a number of tales, often moral, oriental and didactic, such as ‘Malvolio; or Domestic distress’

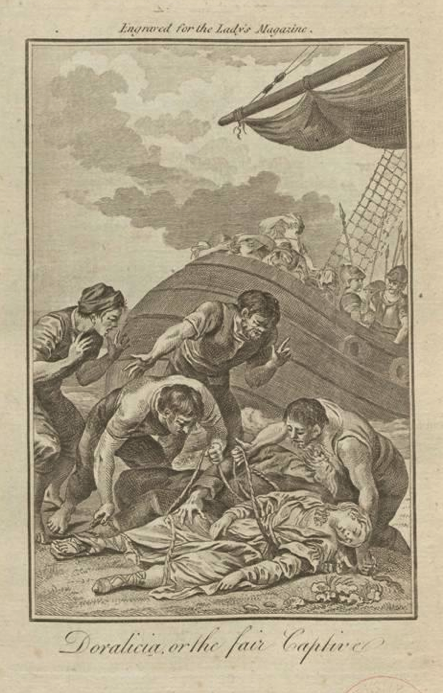

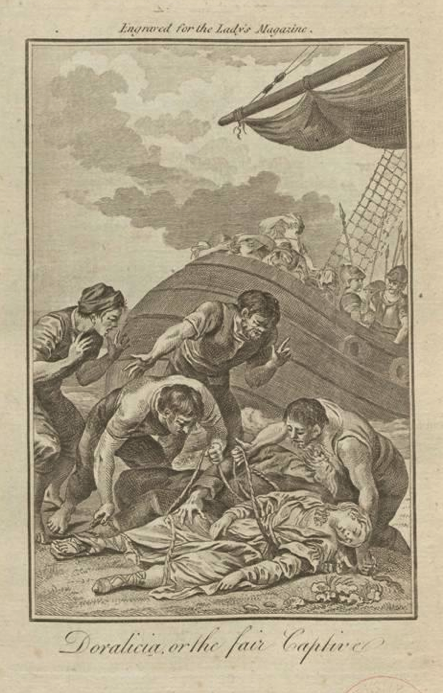

LM VII [July 1776]: 342, ‘Dorilacia, or the fair captive’

LM VII [Sept 1777]: 484, ‘Saccharissa; or the Pitcher Broken’

LM IX [April 1778]: 171, ‘Philidor and Irene, or rural love

LM X [March 1779]: 116, ‘Omrah restored’

LM X [July 1779]: 340, among many others. The tales are often illustrated and such engravings would likely either have to be commissioned after the editors received a tale or be sent to the contributor beforehand in order to match the tale to the engravings. That many of Roberts’ tales are illustrated thus hints at the possibility that Roberts was personally known to the magazine’s editors as a paid or regular contributor.

LM VII [Sept 1777]. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

This information is only a starting point in our ability to map out more clearly the extent of Roberts’ contributions to the magazine and to attempt to uncover a potential relationship with the magazine’s editors or publishers and perhaps discover more about her relationship with Hawkesworth. On these lines, Jennie Batchelor has recently located a letter from Hawkesworth to Roberts held in the library at Harvard that may offer further information regarding this prolific yet largely forgotten translator and writer. While our work here has just begun, it has been a fascinating process so far, and has been a truly collaborative effort of discovery.

Sources:

Kaplan, Marijn S., Translations and Continuations: Ricoboni and Brooke, Graffigny and Roberts (London and New York: Routledge, rept. 2016 [2011]).

Mayo, Robert, The English Novel in the Magazine 1740-1815 (Evanston and London, 1962), catalog entries 225, 226, 287, 311, 314, 463, 859, 985, 1224 and 1260.

Pitcher, E. W., ‘The Miscellaneous Periodical Works and Translations of Miss R. Roberts’, Literary Research Newsletter Vol. 5, No. 3 (Summer 1980): 125-8.

Sherbo, Arthur, ‘Roberts, R. (c.1728–1788)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/69592, accessed 25 Feb 2016]

Sources cited within Sherbo’s ONDB entry: J. Todd, ed., A dictionary of British and American women writers, 1660–1800 (1984) · P. Ripley, ed., A calendar of the registers of the freemen of the city of Gloucester, 1641–1838 (1991) · M. A. Hopkins, Hannah More and her circle (1947) · GM, 1st ser., 58 (1788), 85 · Foster, Alum. Oxon., 1715–1886 [Richard Roberts] · private information (2004) [Betty Rizzo]

Jenny DiPlacidi

University of Kent