As we enter the last few months (gulp!) of our project, new discoveries are throwing themselves at us at a pretty alarming rate. A number of these insights relate to the identities and biographies of some of our authors. The emphasis here, as always, is on the some. We have noted this many times on this blog before, but it bears repeating: the vast majority of reader-contributors who provided original content for the magazine are, and will likely always remain, unknown to us, hidden as they are behind obscure pseudonyms or legal names so common that a week lost in Ancestry trying to find them will never be gotten back.

The figures we have been able to piece biographical details about generally present themselves to us with a little bit of extra detail extra to help us on our attribution way. Often, as in the case of John and Elizabeth Legg or John Webb, this detail takes the form of a place of residence that, along with other clues, has taken us to the relevant archives. Some, like Elizabeth Yeames or C. D. Haynes, are betrayed by brief biographical nuggets offered up in the magazine itself or by easily overlooked asides in that most fabulous resource for the doggedly persistent academic, Notes and Queries.

Others are located by pure serendipity. One such happy accident occurred a few months ago when I was too tired to do ‘proper work’ but unable to sleep. I was messing about on Ancestry and thinking about those magazine contributors I most wanted to know about but didn’t.

LM, 60 (Dec 1809): 549. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

The name of Joanna Squire, or Miss Joanna Squire, as the magazine demurely referred to her, kept resurfacing in my mind. Joanna Squire enjoyed (although as you’ll see, that might not be quite the right word) quite a stint in the Lady’s Magazine. Although her nearly 6 years of publishing with the magazine (between late 1809 and 1815) is not remarkable by the periodical’s standards, the column inches she occupied were significant. In addition to a sole piece of prose – a fragment on hope that appeared in the December 1809 issue – Squire produced a considerable number of poetic works in the first half of the 1810s. Indeed, many single monthly issues of the magazine from these years usually contains 4 or more of her poems.

It was not Squire’s productivity that most impressed me, however; it was her range and spirit. Squire’s poems include completions of ’bouts-rimés’ (poems prompted by rhyming end lines offered up by the magazine to inspire readers), charades and meditations on the fickleness of fortune (a favourite topic). She often wrote poems to and received poetic epistles from other magazine contributors (including Charlotte Caroline Richardson and James Murray Lacey). She was also a patriotic and political poet who wrote a series of works condemning Bonaparte’s public and private life. Her ‘Address to Fortune’, an extempore poem on ‘reading that Bonaparte had deprived his repudiated Josephine of the title of Empress’ from the October 1810 issue, merits a blog post of its own.

Yet this is just one of many poems Squire submitted to the Lady’s Magazine for publication and she remained their ‘respected’ and ‘ingenious’ correspondent, as they were apt to call her, for a significant period of time. At least, that is, until she spectacularly fell out with the magazine’s editors.

In February 1815, the ‘Correspondents’ column of the magazine acknowledged receipt of ‘the very angry epistle of Miss Joanna Squire’ but refused to extend to her the expression of gratitude normally extended to contributors. The circumstances of Squire’s spat with the magazine are unclear, but the magazine’s perturbation is not:

It would be quite easy to refute all her remarks; but after the petulant language, which she has used, she deserves no explanation, and none shall she have.—We recommend to her perusal the speech of Mrs. Caveat, at page 73 of our present Number. (no page)

For the curious, Mrs Caveat – a figure in a regular serial in the magazine in the 1810s – admonishes a companion for want of ‘good breeding’ and ‘petulant’ comments on page 73. I bet you could have guessed that.

From then on, Squire disappears from the Lady’s Magazine and although I had found other works by her in contemporary periodicals, I was drawing a blank in finding her or anything by her after 1815. What happened to her and her talent, I wondered? Had she died not long after the spat with the magazine?

I had looked for her in birth, marriages and deaths records before, but had never found a convincing lead. But that evening my tired and inaccurately typing fingers happened upon a one I hadn’t found before: a Joanna Squires christened on 10 November 1776 in Staines Middlesex. As with my previous efforts to locate Catherine Cuthbertson, I hoped that Squire(s) had lived long enough to see the 1841 census so I could find out more about her and I also hoped that she was considerate and sensible enough not to have married. My initial and disappointed searches drew a blank.

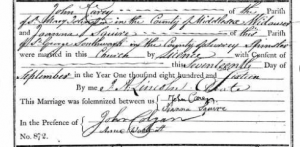

Then, just as I was about to give up, I thought I would try a marriage search again using the information in my new lead: a Joanna born around 1776 in Middlesex. When I found a marriage record for September 1816 to a John Carey in the parish of St George the Martyr, Southwark, I instantly woke up. I knew the name Carey. I knew that a John Carey (could it be this one?), was a literary figure and I knew I had read excepts from his work and odd original pieces in the Lady’s Magazine. Before logging off from Ancestry I did a search for Joanna Carey in the 1841 and 1851 census returns hoping I might be on to something. I was. I found her: as Johanna Carey, a woman of independent means living in the same parish in which she married in 1841; and as Joanna Carey, now living with her servant Elizabeth Jones in Newington High Street, in 1851.

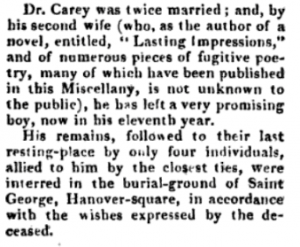

From then it was a few internet searches to assemble a lot of biographical information very quickly. Dr John Carey was easy to pin down. A Dublin born classical scholar, teacher and editor, Carey has his own ODNB page [1], although no mention is made in it of either of his two wives (Joanna was the second). What the ODNB lacked, the Gentleman’s Magazine for 1830 more than made up for. Reporting Carey’s death on 8 December 1829 (the ODNB has Carey’s death date as 1826) in a substantial obituary, the Gentleman’s Magazine gives a generous account of Carey’s career, in part because he was a ‘frequent contributor’ to it himself.

In the penultimate paragraph of the death notice, the obituarist notes that ‘Dr Carey was twice married; and, by his second wife (who, was the author of the novel, entitled “Lasting Impressions,” and of numerous pieces of fugitive poetry, many of which have been published in this Miscellany, is not unknown to the public), he has left a very promising boy, now in his eleventh year.’ John Squire Carey was born on the 29 August 1819 when his mother was in her early forties. He died in 1836 and his mother would outlive him for a further 15 years. When she died in November 1851, she left a will, witnessed by Elizabeth Jones, leaving her estate to her husband’s grandson from his previous marriage, John Carey Garnder.

Uncovering the details of Joanna Squire’s life might not seem all that important beyond fleshing out a footnote in literary history. But for every Joanna Squire, C. D. Haynes, Radagunda Roberts or John Legg we find, we are able to bring into slightly sharper focus what it might have meant to be an author in the period covered by the Lady’s Magazine. And the answer is a messy one. Authors for the Lady’s Magazine didn’t, usually, write in single genres or modes and their careers often spanned decades, marriages, childbirths and deaths. Known Lady’s Magazine authors often did not just write for this title. They fall into and out of love with the magazine as often as twenty-first-century scholars working on it. But thank goodness for serendipity for keeping even the most tired and cynical of researchers energised and keen to find out more.

Notes

[1] W. Sutton, ‘Carey, John (1756–1826)’, rev. Philip Carter, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/4654, accessed 9 Feb 2016]

John Carey (1756–1826): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/465

Dr Jennie Batchelor

School of English

University of Kent

Thank you for this article. John and Joanna Carey were my 5x great uncle/aunt. I’d be very pleased to read anything else you have published on them.