One of the fascinating, yet easily overlooked, genres of the Lady’s Magazine is that of the acrostic (or, as they are often termed, ‘acrostick’) poem. Readily dismissed as amateurish attempts at poetry, the acrostic holds a special place in my heart. The acrostic offers much potentially valuable information about contributors’ names, locations, and names of their beloved/friends/family. The form also depends more on writers’ — and readers’ — ingenuity than it usually receives credit for.

The acrostic poems in the magazine were exploited by the contributors in deliberately revealing ways. Their use is often not merely an attempt to highlight the contributor’s cleverness, but a means of interacting with members of a local geographical community – most often (and this is why I love them) with the object of the writer’s affection. Contributors could give voice to questions, desires, apologies and declarations to those closest to them in their personal lives through the pages of the magazine. The medium of the periodical provided a veil that allowed, in particular, women to voice their desire to men without the danger of being directly observed by a social circle and consequently condemned for forward or coquettish behavior.

The acrostic poems in the magazine were exploited by the contributors in deliberately revealing ways. Their use is often not merely an attempt to highlight the contributor’s cleverness, but a means of interacting with members of a local geographical community – most often (and this is why I love them) with the object of the writer’s affection. Contributors could give voice to questions, desires, apologies and declarations to those closest to them in their personal lives through the pages of the magazine. The medium of the periodical provided a veil that allowed, in particular, women to voice their desire to men without the danger of being directly observed by a social circle and consequently condemned for forward or coquettish behavior.

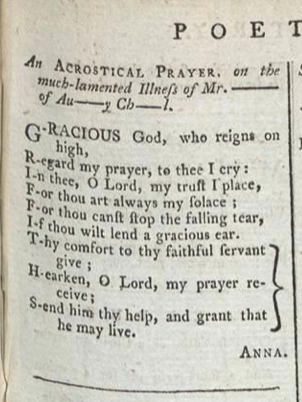

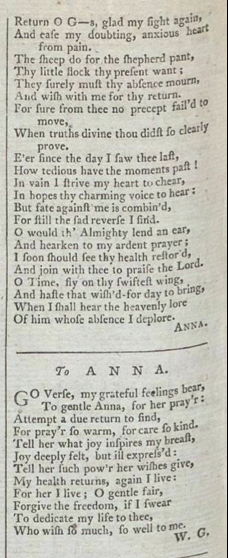

Within the pages of the poetry section, women were able to enjoy a flexible anonymity through which they could literally spell out their desires yet remain obscure enough to avoid any positive proofs of their declarations. 1789 was a particularly fruitful year for acrostic poems and one frustratingly elusive couple in particular drew my attention. A contributor who signed herself ‘Anna’ wrote an acrostic poem in September 1789 entitled ‘An Acrostical Prayer, on the much-lamented Illness of Mr. — of Au—y Ch—l’ (LM XX [Sept 1789]: 495) The poem spells out ‘Griffiths’. Anna’s prayer that Mr. Griffiths recover his health is repeated in November of the same year when she contributes the poem ‘Absence’ (LM XX [Nov 1789]: 604), lamenting the ongoing lack of ‘G—s’ whose health is unrestored.

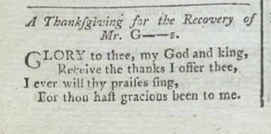

Immediately following Anna’s poem ‘Absence’ appear ‘To Anna’, a short poem that is signed by ‘W. G.’ and states ‘my health returns, again I live’ (LM XX [Nov 1789]: 604) – perhaps the mysterious Griffiths of Au—y Ch—l? In April of 1790 Anna returns to the magazine to offer ‘A Thanksgiving for the Recovery of Mr. G —s’ which offers thanks and praise to God, to whom the poem is addressed. Yet Anna’s hopes for Griffiths’ recovery seem ill-founded. Seven months later, in November of 1790, over a year after her first poem appeared, Anna writes in again. This time the poem seems less joyful and more mournful; less certain and more doubtful. Anna’s poem is less focused on prayers and thanks to God, and more on Griffiths and his impression.

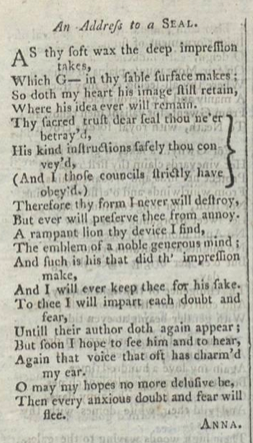

This final poem, ‘An Address to a Seal’, sees Anna turn away from prayer and Christian fortitude and turn to metaphor and imagery. Anna writes ‘As thy soft wax the deep impression takes, Which G—in thy sable surface makes: So doth my heart his image still retain, where his idea ever will remain’ (LM XXI [Nov 1790]: 609). It is not, perhaps, the most original or well-written poem to grace the pages of the magazine. But I think it is honest, and the testament of a woman’s love to a man she knows she may never see again. She is no longer coyly writing his name out in the acrostic; this is a different Anna indeed, who no longer begs ‘O Lord, my prayer receive’ (LM XX [Sept 1789]: 495). Anna in November 1790 addresses Griffith’s seal, not God, writing ‘And I will ever keep thee for his sake. To thee I will impart each doubt and fear’ (LM XXI [Nov 1790]: 609) – almost as though she has turned away from the God to whom she had once offered thanksgiving for Griffiths’ recovery, only to see him fall ill again.

Anna never writes about ‘G’, ‘G—s’, or ‘Griffiths’ again. Her final lines in ‘An Address to a Seal’ that ‘O may my hopes no more delusive be, then every anxious doubt and fear will flee’ (LM XXI [Nov 1790]: 609) remain, for us, unanswered. In spite of having spent hours searching for traces of a W. Griffiths or Anna (possible Anna Griffiths) of Au—y Ch—l, I’ve yet to find anything definitive. Even though Anna is not one of the magazine’s most prolific or talented contributors, she is characteristic of the magazine’s many nameless, faceless writers: she voices her hopes, fears and love; she evolves through the pages of the magazine, she shares a little bit of her heartbreak and her world, and then she disappears.

Jenny DiPlacidi

Really no matter if someone doesn’t know then its up to other users that they will help,

so here it takes place.