1918 was a big year for suffrage in the UK, with not only women being allowed to vote in parliamentary elections for the first time, but men over the age of 21 were also given the vote and the first woman, Constance Markievicz, was elected to the House of Commons.

100 years ago this week, on the 6th February, the Representation of the People Act 1918 was passed. This meant that, after decades of campaigning, women had finally won “the full rights of citizenship”. Well, some women at any rate. The Act allowed women over the age of 30, who met certain financial and/or locational criteria, to vote in the parliamentary elections. Other changes within the act also allowed all men over the age of 21 the vote, where previously only men over the age of 30, or over the age of 21 who met certain financial criteria, could do so. So, in essence, in 1918 women took a huge step forward to be equal with men, and the men moved the goal posts at the same time. One reason for the decision to not equally enfranchise women could be that, after the loss of so many men in the First World War, had women over the age of 21 also been given the vote in line with men then women would have had the majority (and we couldn’t have that, could we?) So women had to wait a further decade to be equally enfranchised.

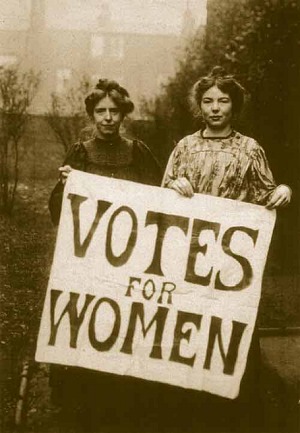

Even so, we cannot deny that this was one of the most momentous moments of the 20th Century, nor can we ignore the huge amount of time, dedication and personal sacrifice that went into achieving it. The first petition to parliament requesting that women be given the vote was presented by Mary Smith in 1832 but this (and numerous subsequent petitions and suggested amendments to the law) was not successful. In 1897 The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was formed, with Millicent Fawcett at its head. In 1903 the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) was formed by Emmeline Pankhurst, allegedly frustrated by the NUWSS’s lack of direct action. What followed were hunger strikes, vandalism and arson from the now so called “suffragettes” (a term is coined in 1906), and in retaliation they were subjected to imprisonment, brutal force feeding, beatings, the loss their families and, in some cases, death. The most notorious of all deaths, it could be argued, was that of Emily Wilding Davison who, on the 4th June 1913, walked onto the track during the Epsom Darby and was hit and killed by King George V’s horse.

So, 100 years later, where are we now? Well, on the political front we are still looking at a serious deficit: women make up more than half of the population of the UK, but less than a third of MPs. We might have a woman PM but she has been forced to look at criminalising the abuse and intimidation of political candidates, in response to an inquiry by the Committee on Standards in Public Life that found that women candidates (as well as ethnic minority and gay candidates) were disproportionately subjected to abuse in last year’s general election. There’s no doubt that we have progressed a lot in the last 100 years, with achievements such as the Abortion Act 1967, the Equal Pay Act 1970 and the Sex Discrimination Act 1975. But we still have a sizable gender pay gap, caused largely by women still taking on significantly more caring responsibilities; two women are killed each week by a current or former partner in England and Wales; and more men named John run FTSE 100 companies in the UK than women.

We owe a huge debt of gratitude to the Suffragists and Suffragettes of the last century for getting the ball rolling on equality, but there is still a long way to go to achieve it entirely.