An important element of reconstructing musical instruments is making sure they are made out of the right stuff. In making our replicas of the bells, cymbals, pipes, and clappers in the Petrie Museum, we need to make sure we are using materials that are as close to those of the originals as possible – this gives us the best chance of ensuring that they will make the same sounds as the original artefacts. For example, the kind of alloy used in the cymbals will affect the resonance and tone of the sound they create when struck. So it is important to get it right! This is where compositional analysis (and a fair bit of science) comes in.

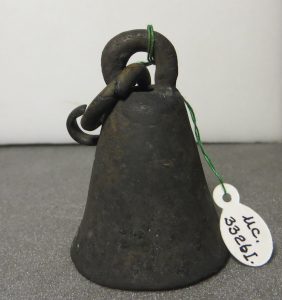

We have been using an XRF machine to find out exactly what our metal musical instruments are made of. The XRF (“X-Ray Fluorescence”) machine uses radiation to identify the elements present in an object; the x-rays cause the artefacts to emit radiation that is characteristic of its own elemental makeup, allowing the equipment to identify the component parts (if anyone wants a more scientific explanation, see here!). In the case of our metal artefacts, the XRF tells us exactly what the ratio of different metals were in each alloy used. All the bells and cymbals seemed to be variations of copper alloy, either towards brass (an alloy of copper and zinc) or bronze (an alloy of copper and tin) – however the compositional analysis has ensured we know exactly the ratios of these, and therefore can choose the most suitable modern alloy for the replicas.

The XRF machine is a fairly hefty bit of kit, thanks to the lead lined case that it comes with – this contains the object when exposed to the X-ray, and keeps us safe from the radiation. It is however portable enough for it to come up to the Petrie for a day’s worth of compositional analysis. To get accurate results, the objects need to have a clean surface – the artefacts in the Petrie are great for this as, by and large, they were thoroughly cleaned and conserved post-excavation, preserving their surface. Thus many of our readings were accurate enough to identify traces of gold, as well as the more usual bronze, brass, and iron, which suggests the presence of gilded surfaces now deteriorated and no longer visible to the eye.

Now we have this data, we can undertake the next step – meeting with our replica makers to discuss the most appropriate alloys to use, as well as which manufacturing techniques should be used to ensure their authenticity.