Generally speaking, conflict assessments are conducted with the aim of improving the effectiveness of conflict prevention and management programmes and strategies. One such approach is to map out a conflict and current responses to it and to analyse future policy options 1. Mapping a conflict can constitute a first step on the road to designing and implementing an effective peacebuilding strategy 2. In this article of the blog series on conflict mapping I will be using the framework to understand and analyse the Syrian civil war. Nearly seven years after a peaceful uprising against President Bashar al-Assad descended the country into civil war, the Syrian conflict is sadly as relevant as ever.

Summary description

In 2011, during what came to be known as the Arab Spring, popular uprisings toppled President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali of Tunisia and President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt 3. Syria, too, erupted in peaceful protests that March, but the government responded with a brutal crackdown on demonstrators. The Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has lost control of large portions of the country, as well as credibility due to the deliberate slaughter of civilians and the use of chemical weapons 4. The civilian and military opposition has not formed into a credible movement with a unified approach. This is partly due to sectarian and extreme ideologies of some opposition groups 5. A violent extremist group known as the Islamic State (IS) has, until recently, grown in influence throughout the conflict. The war has created a humanitarian crisis of immense proportions, with 13.5 million people requiring humanitarian assistance and with over half the population displaced from their homes 6. In 2016 the war was the largest source of displacement in the world 7. As the war carries on, the list of challenges to peacebuilding grows more and more daunting – the sheer number of conflict drivers along with their interconnected nature has made the conflict seem intractable 8.

Issues and context

The Syrian civil war is a result of complex and interlinked long- and short-term causes, including socio-political and religious tensions, poor economic situation, and the wave of political uprisings sweeping across the Middle East and North Africa in 2011 9. Initially, long-standing lack of freedoms and economic hardship fuelled rising resentment toward the government 10. The Assads belong to the Shia Alawite minority, and Alawites have dominated high-ranking positions in the military and government since 1970. Sunni majority resentment of Hafez al-Assad’s oppressive rule eventually led to the Islamist uprising in 1978, which ended with the Hama massacre of 1982 11. Although the protests that started in 2011 were, for the most part, non-sectarian, clear sectarian and ethnic divisions emerged as a result of armed conflict 12.

The level of government oppression, the economic and political exclusion of groups, and the prevailing culture of structural violence all fed into an atmosphere of resentment 13. A decade of economic stagnation and challenges associated with climate variability and drought are factors that should not be overlooked because they played an important role in the deterioration of the country’s economic situation 14. From 2006 to 2011, Syria experienced a severe drought that contributed to agricultural failures, to population displacement and mass migration from the rural areas to the cities. The drought pushed a million people into food insecurity. All of this contributed to urban unemployment and social unrest 15.

Conflict history

The successful uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia energised the anti-government movement in Syria. After the pro-democracy protests erupted in March 2011, the Syrian government responded by killing and imprisoning hundreds of protesters. In July of the same year defectors from the military formed the Free Syrian Army, an anti-government rebel group. From this point on Syria began its rapid descent into civil war 16. Opposition supporters began to take up arms, initially in self-defence and then to fight government forces for control of towns and cities 17.

A significant dimension of the war in Syria has been the perpetration of war crimes and the use of chemical weapons by Syria’s government 18. According to a UN commission of inquiry on Syria, there is evidence that the Syrian government has repeatedly used chemical weapons against civilians in rebel-held areas 19. In March 2015, the UN Security Council adopted a resolution condemning the use of chlorine as a weapon and threatening action under Chapter VII of the UN Charter. Further chemical attacks continued to be made through 2015-2017, by the government forces and by the Islamic State. The mandate of the OPCW-UN joint investigative mechanism, which determines actors responsible for chemical attacks in Syria, expired on 17 November 2017 after several attempts to extend it were all vetoed by Russia in the UN Security Council 20.

Parties

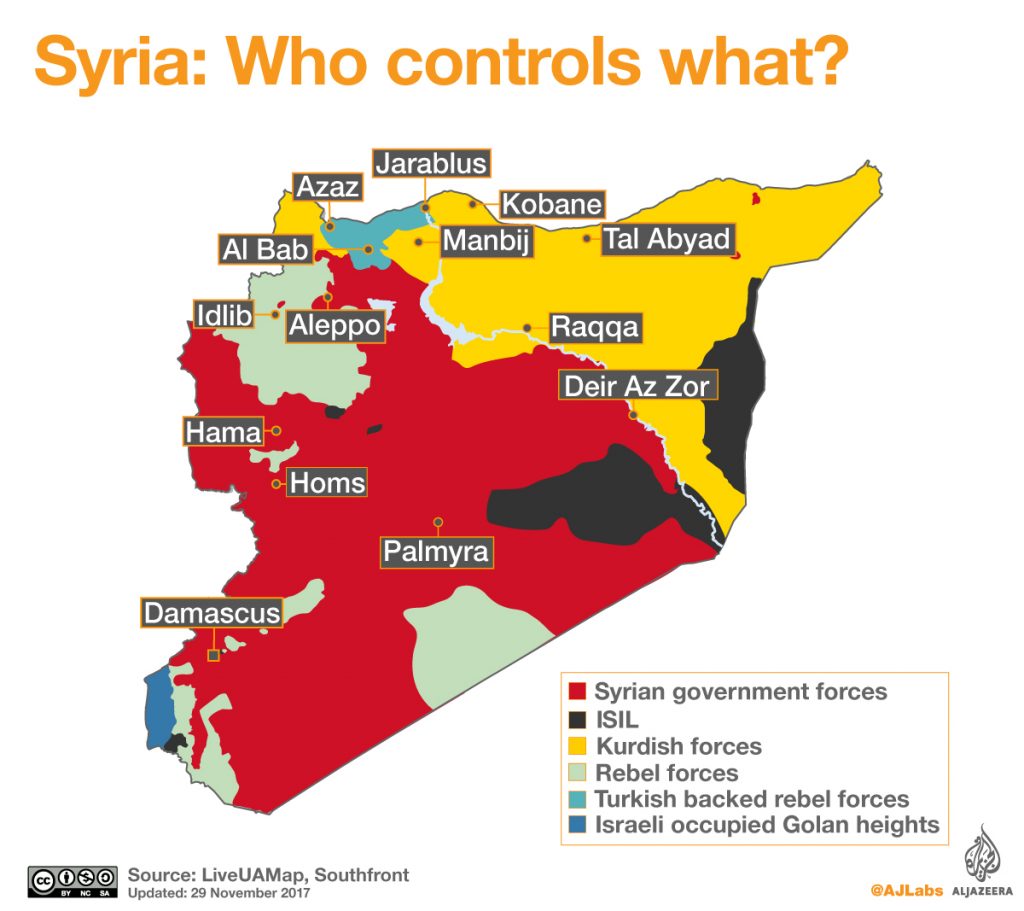

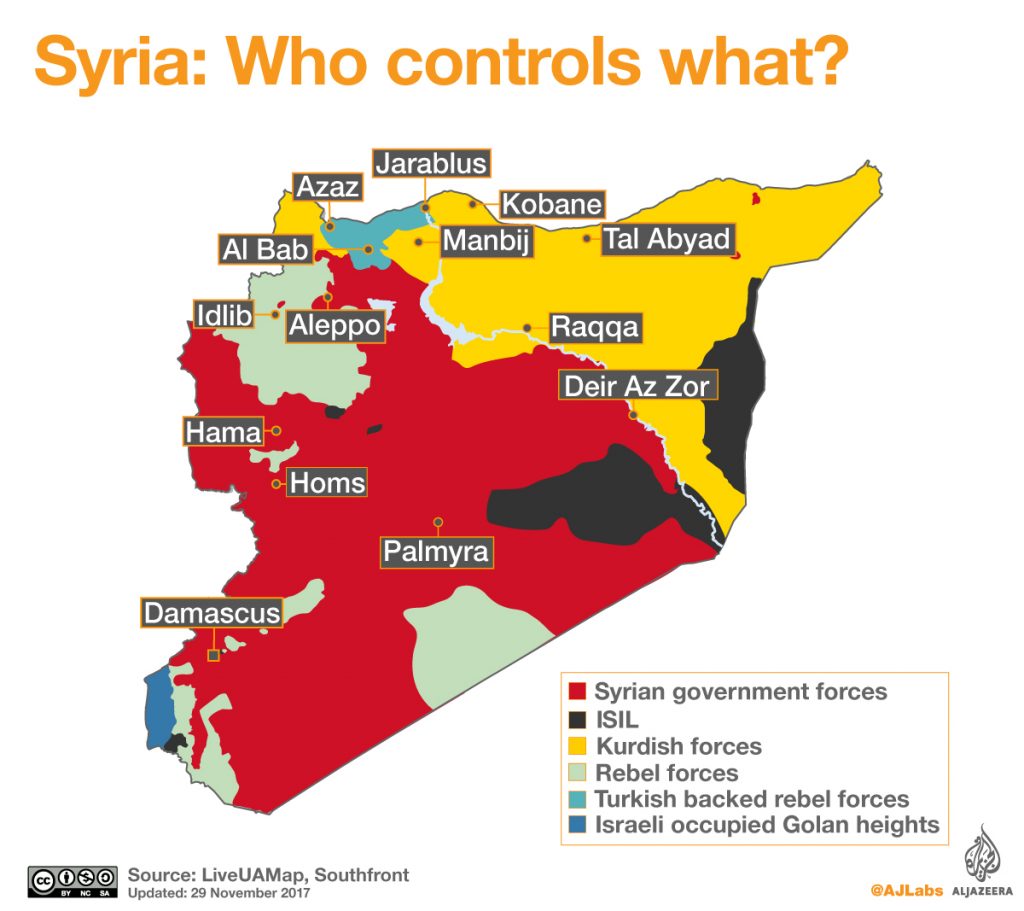

The primary conflict parties can broadly be divided into pro-regime actors; the numerous rebel groups who form the opposition; and the group known as the Islamic State (IS) 21. The conflict has also been characterized by a high degree of international involvement 22.

Pro-regime actors:

- Bashar al-Assad and his Ba’ath party.

- The Syrian Armed Forces (SAF).

- Paramilitary National Defence Forces (NDF).

Opposition:

- Hundreds of groups that differ widely in their ideologies and visions for the future of Syria. The opposition has therefore struggled to generate a country-wide organised structure that would enjoy local and international legitimacy 23.

- Islamist groups, such as the Al Qaeda-affiliated Jabhat al Nusra.

- Free Syrian Army (FSA).

- Salafist and Salafi-jihadist groups, the latter calling for violent struggle as an individual duty to establish their specific vision of Islamic order 24.

- Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and the People’s Protection Units (YPG).

- Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

- Islamic State (IS).

International involvement:

- Russia and Iran back the Syrian government.

- Turkey supports some rebel groups, namely the FSA, to fight against the SDF and IS 25. Turkey’s most pressing concern is the potential for an autonomous Kurdish entity near the Turkish border 26.

- The United States leads an international coalition set up to combat IS 27. As the conflict escalated the US faced pressure to intervene, but its support for the opposition has been hesitant and inconsistent. This has been largely due to lack of a cohesive moderate opposition and the strong influence of Islamist movements 28.

- Saudi Arabia has provided support to several rebel brigades 29.

Dynamics

The civil war is more than just a battle between pro- and anti-Assad groups. There are clear sectarian overtones, with tension between Syria’s Sunni majority and the President’s Shia Alawite sect. According to a comprehensive conflict analysis by the ARK Group, “the instrumentalisation of sectarian, religious, and ethnic identities has become a centrepiece of current conflict dynamics” 30. Other important dynamics that have contributed to the escalation of violence, spiralling and polarization include the level of violence against civilians; varying foreign intervention; fragmented opposition; and the presence and influence of extremism 31. Civilian involvement in the war and the perception of civilians as legitimate military targets by both the regime and non-regime actors sustains fear, fuels recruitment into armed and extremist groups, and exacerbates the already immense refugee crisis 32.

Although now lacking in unity, it could be argued that the revolution began with a unified aim – a non-violent demand for political and socioeconomic reform. However, the opposition was decentralised and had no recognised leaders, which soon enough led to a lack of coherence. In-fighting and disorder has led to public distrust of the opposition’s capacity to lead the country and has even contributed to the rising support for Islamist groups that have greater internal cohesion 33. Disparate foreign intervention is another important conflict dynamic. The anti-regime international coalition has been poorly coordinated due to diverging interests and motivations. Meanwhile, the pro-Assad coalition has demonstrated more unity and has made more significant investments 34. Foreign intervention has protracted the conflict by extending the finite capabilities of the direct actors, leading to a proxy war unlikely to end in decisive victory for one side over the other 35.

Conflict regulation potential and alternative routes to solutions

There have been several international initiatives attempting peace negotiations, with the two main diplomatic tracks being the UN-led negotiations in Geneva, and the Russian and Turkish facilitated talks in Astana. The fate of President Assad and a transitional government have been major sticking points between the Syrian government and opposition groups 36, and negotiations have been repeatedly suspended due to disagreements over the priority of humanitarian issues. The talks in Astana have had slightly more success. During the sixth round of talks in Astana, four “de-escalation zones” were set up in mainly opposition-help parts of the country 37. This was a sign of progress, but questions loom over its implementation. The agreement has already been arguably undermined, with reports of pro-regime forces conducting airstrikes in the zones 38.

The conflict in Syria appears in many ways intractable. The influence of non-state extremist groups makes it very difficult to reach a negotiated solution. Their uncompromising and existential threat makes it extremely unlikely for them to be included at the negotiating table, therefore increasing the likelihood that they will act as spoilers in the peace process 39. Addressing the level of violence against civilians needs to be first priority. In addition to reducing human suffering and impacting the refugee crisis, this would go some way toward reducing the appeal of extremist groups, and starting to build trust in the potential for a peaceful resolution 40. Syria has a large population of civil society organisations within the opposition, including activists and professionals who deliver services and humanitarian aid with the help of international aid organisations 41. Prospect for resolution may arise from utilising and empowering these local grassroots organisations.

Conclusion

The conflict in Syria is immensely complex and things are constantly changing at a rapid pace. Within the scope of this conflict map it has only been possible to provide a very surface-level analysis of the history, context, parties, issues and dynamics at this point in time. I also provided an overview of how the peace process has progressed thus far, and an analysis of the potential for future resolution. Solutions to local issues must be devised and revised based on a thorough understanding of the current situation, of the conflict drivers and their interplay with regional and international dynamics, and an approach based on research and evidence. Internal drivers of conflict may remain unresolved in the face of outside intervention, which is why a comprehensive understanding is vital to achieving peace 42.

By Julia Rinne

(ed. Marie Hoffmann)

Bibliography

1: Department for International Development (DFID) (2002) “Conducting Conflict Assessments: Guidance Notes”, pg. 5, available at: http://www.swisspeace.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/Media/Topics/Peacebuilding_Analysis___Impact/Resources/Goodhand_Jonathan_Conducting_Conflict_Assessments.pdf

2: Wehr, P. (1979) Conflict regulation. Boulder, Colo.: Westview, pg. 18

3: Al Jazeera (2017) “Syria’s Civil War Explained From the Beginning”, Al Jazeera, 1 October, available at: http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/05/syria-civil-war-explained-160505084119966.html

4: ARK Group DMCC (2016) “The Syrian Conflict: A Systems Conflict Analysis”, pg. 13, Available at: http://cdacollaborative.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/The-Syrian-conflict-A-systems-conflict-analysis.pdf

5: ARK Group DMCC (2016) “The Syrian Conflict: A Systems Conflict Analysis”, pg. 13

6: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) (2017) About the Crisis. Available at: http://www.unocha.org/syrian-arab-republic/syria-country-profile/about-crisis

7: ARK Group DMCC (2016) “The Syrian Conflict: A Systems Conflict Analysis”, pg. 12

8: ARK Group DMCC (2016) “The Syrian Conflict: A Systems Conflict Analysis”, pg. 8

9: Gleick, Peter H. (2014) “Water, Drought, Climate Change, and Conflict in Syria”, Weather, Climate, and Society, vol. 6, pg. 331

10: Al Jazeera (2017) “Syria’s Civil War Explained From the Beginning”, Al Jazeera, 1 October

11: ACAPS (2017) Crisis Analysis of Syria. Available at: https://www.acaps.org/country/syria/crisis-analysis

12: Al Jazeera (2017) “Syria’s Civil War Explained From the Beginning”, Al Jazeera, 1 October

13: ARK Group DMCC (2016) “The Syrian Conflict: A Systems Conflict Analysis”, pg. 34

14: Gleick, Peter H. (2014) “Water, Drought, Climate Change, and Conflict in Syria”, Weather, Climate, and Society, vol. 6, pg. 331

15: Gleick, Peter H. (2014) “Water, Drought, Climate Change, and Conflict in Syria”, Weather, Climate, and Society, vol. 6, pg. 332-4

16: Al Jazeera (2017) “Syria’s Civil War Explained From the Beginning”, Al Jazeera, 1 October

17: BBC (2016) “Syria: The Story of the Conflict”, BBC, 11 March, available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-26116868

18: BBC (2016) “Syria: The Story of the Conflict”, BBC, 11 March

19: Human Rights Council, Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, 36th session, A/HRC/36/55, 8 August 2017, available at: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/IICISyria/Pages/IndependentInternationalCommission.aspx

20: Arms Control Association (ACA) (2017) “Timeline of Syrian Chemical Weapons Activity, 2012-2017”, 17 November, available at: https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Timeline-of-Syrian-Chemical-Weapons-Activity

21: BBC (2017) “What’s happening in Syria?”, BBC, 3 November, available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/16979186

22: Erickson, Amanda (2017) “Things Are Moving Fast in Syria. Here Are Answers to 7 Key Questions About the Conflict”, Washington Post, 7 April, available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/04/07/things-are-moving-fast-in-syria-here-are-answers-to-7-key-questions-about-the-conflict/?utm_term=.4fe0bcced1a2

23: ARK Group DMCC (2016) “The Syrian Conflict: A Systems Conflict Analysis”, pg. 19

24: ARK Group DMCC (2016) “The Syrian Conflict: A Systems Conflict Analysis”, pg. 14-5

25: ACAPS (2017) Crisis Analysis of Syria. Available at: https://www.acaps.org/country/syria/crisis-analysis

26: ARK Group DMCC (2016) “The Syrian Conflict: A Systems Conflict Analysis”, pg. 28

27: ACAPS (2017) Crisis Analysis of Syria. Available at: https://www.acaps.org/country/syria/crisis-analysis

28: ARK Group DMCC (2016) “The Syrian Conflict: A Systems Conflict Analysis”, pg. 26

29: ARK Group DMCC (2016) “The Syrian Conflict: A Systems Conflict Analysis”, pg. 26-7

30: ARK Group DMCC (2016) “The Syrian Conflict: A Systems Conflict Analysis”, pg. 15

31: ARK Group DMCC (2016) “The Syrian Conflict: A Systems Conflict Analysis”, pg. 33

32: ARK Group DMCC (2016) “The Syrian Conflict: A Systems Conflict Analysis”, pg. 36-7

33: ARK Group DMCC (2016) “The Syrian Conflict: A Systems Conflict Analysis”, pg. 39-40

34: ARK Group DMCC (2016) “The Syrian Conflict: A Systems Conflict Analysis”, pg. 46-7

35: ARK Group DMCC (2016) “The Syrian Conflict: A Systems Conflict Analysis”, pg. 57

36: Al Jazeera (2017) “Syria Diplomatic Talks: A Timeline”, Al Jazeera, 15 September, available at: http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/09/syria-diplomatic-talks-timeline-170915083153934.html

37: Al Jazeera (2017) “Final De-escalation Zones Agreed on in Astana”, Al Jazeera, 15 September, available at: http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/09/final-de-escalation-zones-agreed-astana-170915102811730.html

38: Homsi, Nada and Barnard, Anne (2017) “Marked for ‘De-escalation’, Syrian Towns Endure Surge of Attacks”, New York Times, 18 November, available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/18/world/middleeast/syria-de-escalation-zones-atarib.html

39: ARK Group DMCC (2016) “The Syrian Conflict: A Systems Conflict Analysis”, pg. 45

40: ARK Group DMCC (2016) “The Syrian Conflict: A Systems Conflict Analysis”, pg. 53

41: ARK Group DMCC (2016) “The Syrian Conflict: A Systems Conflict Analysis”, pg. 20

42: ARK Group DMCC (2016) “The Syrian Conflict: A Systems Conflict Analysis”, pg. 9

Photos:

43: Al Jazeera (2017) “Syria: Who Controls What?”, Al Jazeera, 29 November, available at: http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/interactive/2015/05/syria-country-divided-150529144229467.html

44:https://theburningbloggerofbedlam.files.wordpress.com/2014/12/syria-grief-fromdc2iowa-blogspot.jpg