Dr Kate Rennard (University of Kent)

Research Associate, ‘Beyond the Spectacle’

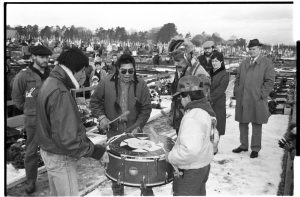

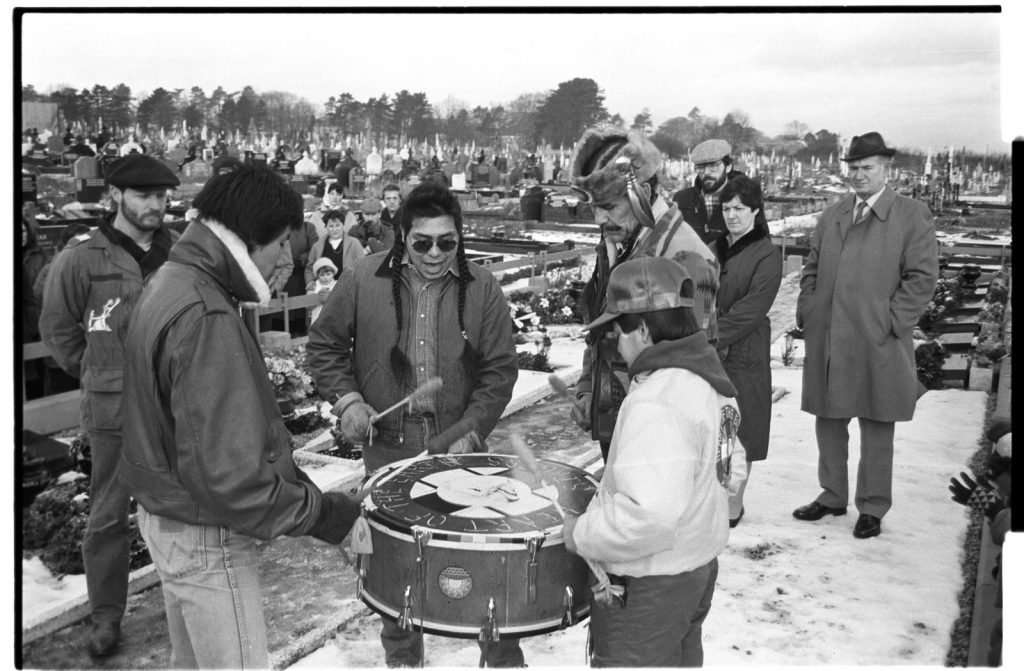

Credit: Belfast Media Group.

On a bitterly cold January morning in 1985, members of the American Indian Movement (AIM) and students from their Heart of the Earth Survival School in Minneapolis visited the Irish Republican plot of the Milltown Cemetery in Belfast, Northern Ireland. With an audience that included Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams and the parents of hunger striker Kieran Doherty, AIM activists laid a wreath at the plot and played the Movement’s anthem. The next day, they attended the Bloody Sunday march, once more laying a wreath and singing in memory of those who had been killed, this time by British soldiers in Derry over a decade earlier. As AIM leader Clyde Bellecourt told the Irish Times, the AIM activists had “come to pay respects to people who had given their lives for peace, equality and liberty in their homeland, the aspirations for which American Indians were struggling in their homeland.”[1]

Just over a year later, a group gathered in Wales for a commemorative ceremony at the graves of the ‘Abergele Martyrs,’ two Welsh nationalists killed during a bombing campaign in 1969. Among them were Ojibwe activist Mark Banks, brother of AIM leader Dennis Banks, and members of Ty Cenedl, the grassroots Welsh nationalist movement that had organised his visit. (Ty Cenedl focused on raising consciousness of Wales’s history as a colonised nation, erecting monuments and organising commemorations of significant events.) During the ceremony, Banks “proudly and suitably honoured” the ‘Abergele Martyrs’ by saying a few words and making a tobacco offering at each grave. In return, Banks asked one thing of the Ty Cenedl members: one day, a Welsh person would travel to the graves of “fallen A.I.M. dead patriots” from the Movement’s siege at Wounded Knee, South Dakota in 1973 and similarly honour them.[2]

The actions of these AIM activists in Ireland and Wales represented part of a decades-long story of communication, cooperation, and exchange between AIM, Irish Republicans, and Welsh nationalist groups and suggests ways in which memory and commemoration shaped their transatlantic relationships. The American Indian Movement was founded in Minneapolis in 1968 and gained national notoriety with high-profile protests such as the siege at Wounded Knee in 1973. Beginning in the aftermath of the siege, AIM activists, Irish Republicans, and Welsh nationalists exchanged information about their struggles and tactics, built networks, and carried out political activities in support of each other’s campaigns. The communal remembering for Irish hunger strikers, the Abergele Martyrs, and the AIM members who died at Wounded Knee represented an important aspect of these relationships, however, in that they challenged the existing state narrative of these events that marked these deaths as not worthy of mourning. Those who died in the Irish hunger strikes, Abergele, and Wounded Knee had all been labeled as ‘insurgents’ or ‘terrorists,’ as not grievable, to use Judith Butler’s term.[3] As Clyde Bellecourt remarked during his visit to Northern Ireland, “We too are called terrorists in our homeland…They have criminalised this Movement as they attempt to criminalise the struggle that is taking place here in Ireland.”[4] These labels served to further isolate the populations involved by portraying their losses as insignificant. By paying their respects to each other’s fallen activists, AIM, Sinn Féin, and Ty Cenedl instead engaged in a mutual commemoration and recognition of each other’s struggles and griefs. As Mark Banks recalled of his time in Wales, “All that support gave me the strength, saying there are people out there who believe in me, and believe in AIM and believe in Native Americans…It makes you go on.”[5] Certainly, each movement’s reasons for supporting each other were not simply altruistic and often had political motivations. For many participants though, these relationships provided reassurance that they were not alone in their struggle and that others thought their losses worth remembering.

These movements also learned important lessons from each other in healing from their experiences of colonisation. In 2001, for example, Sinn Féin’s newspaper ran an article about the 20th anniversary of the deaths of Irish Republican hunger strikers. Yet it began with a story of Wounded Knee in 1890, describing how an AIM delegation visiting Northern Ireland in 1990 had “talked of their preparations to move from a period of mourning to one of healing.” Recalling how this coincided with the tenth anniversary of the hunger strike deaths, the article noted, “for many of us, it will always seem like yesterday.” The reporter left her readers with the thought that while this event, like the memory of Wounded Knee, belonged to the past, it also “remains part of the demand for change and the enduring will to achieve it.”[6] The lesson here was clear: these tragic events would always haunt the peoples involved and the past would always have a presence, but this could be used productively to challenge their colonisation.

The relationships AIM forged with Irish Republicans and Welsh nationalists contributed to each movement’s politics of remembering, not only demonstrating that those who had lost their lives for the campaigns were worthy of commemoration, but also providing strategies for combating nation-state violence through memory. These transnational relationships provide a window into some of the complicated and diverse ways that Indigenous peoples have shaped the political landscape here in the UK.

[1] Martin Cowley, “5,000 Recall Bloody Sunday,” Irish Times, Jan. 28, 1985, 9.

[2] “Official Tour Report,” Folder 5, Box CXII, Ty Cenedl Papers (National Library of Wales).

[3] Judith Butler, Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? (New York: Verso Books, 2009).

[4] Clyde Bellecourt, “Clyde Bellecourt in The Mill,” Andersonstown News, Feb. 9, 1985, 24.

[5] Mark Banks, interview by Kate Rennard, Monument, CO, July 13, 2010.

[6] Laura Friel, “We Shall Overcome,” An Phoblacht, March 1, 2001.

Thanks, both! I’m glad you enjoyed the piece.

Powerful words. The past will always return to tell its story.

A fascinating read. Abergele is my hometown. The annual commemorative march for the ‘martyrs’ is viewed somewhat controversial. I had no idea of the AIM and Mark Banks’ visit though. Thank you for this.