Professor Jacqueline Fear-Segal (UEA)

Co-Investigator, ‘Beyond the Spectacle’

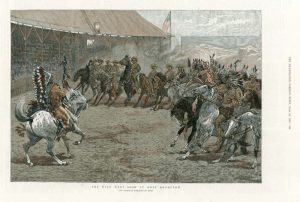

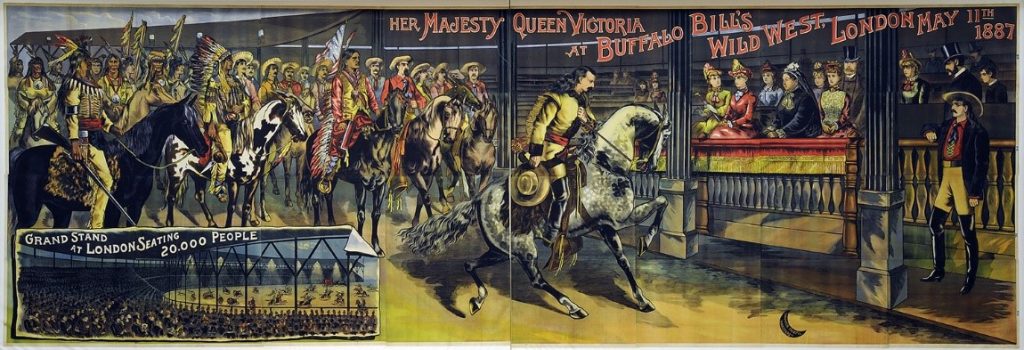

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show had already thrilled huge audiences in the USA when in 1887 it crossed the Atlantic to take London by storm. Crowds thronged the streets to catch a glimpse of the cavalcade of over 800 performers, 180 horses, 18 buffalo, 10 elk, 2 deer, and 5 Texas longhorns as they arrived at a purpose built arena in Earl’s Court. Two and a half million Londoners would buy tickets to see the Show’s extravagant rendering of life on America’s Wild West frontier. William Cody (aka Buffalo Bill) later noted in his autobiography, “When our spectacle was finally given it was received with such a burst of enthusiasm as I had never witnessed anywhere.”

Sharp shooting Annie Oakley, a buffalo hunt with real American bison, and a cyclone that blew a whole Indian village “out of existence for the delectation of the English audience”, were all part of this extravaganza that electrified the spectators. But it was the “Indians” who stole the show. Their ferocious attacks on a wagon train, a stage coach, and then a settler’s cabin, each cut short by the heroic arrival of William Cody and his troops, delighted the crowd and simultaneously enshrined a simplified, triumphant, colonialist account of American history and “Indian savagery” that would endure down the years. As Joy S. Kasson has noted, “The Wild West’s very hybridity –rooted in the most clichéd melodramas and the most grandiose political rhetoric, claiming authenticity and mobilizing show-business glitz—made it powerfully persuasive”.

Powerfully persuasive and the apotheosis of spectacle, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show lies at the core of this project’s concerns. It enabled millions of Britons to see “real live Indians” and to believe that they now understood both the romance and horror of “savagery”, and the three tours also brought to Britain larger groups of Native Americans than had ever previously crossed the Atlantic. All of them travelled far and wide across the country, visiting more than 170 English, 30 Scottish, and 20 Welsh towns and cities, before (for the majority) carrying their memories and stories back home to their reservation communities.

On this blog site, we will return numerous times to explore and discuss different aspects of the three separate tours Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show’s completed in Britain –1887-88; 1891-92; 1903-4. In this post, I want to start with an exploration of the historical background of the show “Indians” who travelled to England in 1887, in order to look “beyond the spectacle” and catch glimpses of their lives and their community experiences.

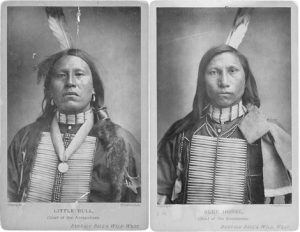

By the time the Show travelled to London for the first time Cody was almost exclusively hiring Lakota, predominantly from the Pine Ridge and Rosebud agencies in Dakota Territory. This was sometimes confusing as the Lakota were also required to represent other tribes, not just in the arena but on publicity cards; for example, Little Bull (Lakota) was presented as “Chief of the Arapahoes,” and Blue Horse (Lakota) as “Chief of the Shoshones”

For Cody, this Lakota recruitment policy alleviated inter-tribal rivalries and only required the services of a single interpreter. It also added a titillating savour of authenticity when “Custer’s Last Stand” was re-enacted little more than a decade after it had taken place (in 1876). The recruitment policy also meant that the Show “Indians” all shared the same recent, troubled historical past. Although there were seven separate Lakota bands and within these there were divisions and different views, all had been touched by warfare with the U.S. Army and the government’s relentless drive to confine them on reservations and acquire their Dakota homelands.

When the Lakota boarded the S.S. State of Nebraska in April 1887 to travel to England, Congress had just passed the Dawes General Allotment Act. This Act would prove disastrous for all Native Americans because it legalized the destruction of their communal land holdings, thus facilitating their progressive dispossession.

Created in 1868 by the Treaty of Fort Laramie and then illegally whittled away in 1876, the Great Sioux Reservation was again reduced and fragmented in 1889. Hundreds of American settlers arrived to set up farms on traditional Sioux hunting grounds, bringing Dakota Territory into the Union as two states: North and South Dakota.

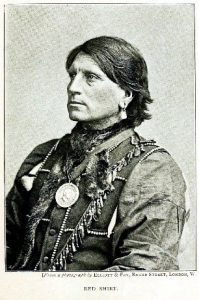

In England, when responding to a question about the future of his people posed by a reporter from the Central News, Red Shirt, who was the main spokesman for the “Indians”, gave an answer that was tactful but honest:

The Indian of the next generation will not be the Indian of the last. Our buffaloes are nearly all gone: the deer have entirely vanished; and the white man takes more and more of our land. But the United States government are good. True, it has taken away our land, and the white men have eaten up our deer and our buffaloes. But the Government now give us food that we may not starve. They are educating our children….Now we are dependent on the rations of the Government, but we feel we are entitled to that bounty. It is a part of the price they pay for the land they have taken from us, and some compensation for us for having killed off the herds upon which we subsisted. For myself, I know it is no use fighting against the United States Government.

Red Shirt’s words plainly state the desperate situation of the Lakota and perhaps also serve as a tacit explanation for why he had joined the Show. Although he was speaking to a reporter through an interpreter, his speech offers a good example of how interviews in newspaper articles such as this can be read across the grain to reveal evidence of Native Americans’ views and concerns. However, despite Red Shirt’s candour, it is extremely unlikely that, in the absence of images like the one below, readers would have been able fully to imagine what this total dependence on government rations for food and clothing entailed for Red Shirt and his people.

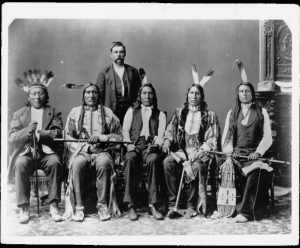

Red Shirt, like many others who signed up with William Cody –including American Horse (Wasicu Tasunke), Blue Horse (Sunkawakhan Tho), Little Bull (Tatanka Ciqala), Little Chief, and Flies Above– had been a warrior and had already earned his place as a headman and diplomat. In 1880, he had been the youngest member of Red Cloud’s Pine Ridge delegation to Washington D.C., where he joined headmen Red Dog, Little Wound, and American Horse, along with more than thirty other Sioux leaders to sign an agreement granting the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad a right of way across Sioux lands. Awareness of such events alerts us to the status of many of the Lakota Wild Westers and to the leadership roles they held in their own communities, before becoming performers and “playing Indian” for the amusement of the British public.

(L-R: Red Dog, Little Wound, John Bridgman (interpreter), Red Cloud, American Horse, Red Shirt)

In England, William Cody had appointed Red Shirt “Chief of the Sioux”, but perhaps did not realise the experience he had already accrued as an ambassador. In his autobiography, Cody writes:

It was interesting to watch old Red Shirt when he was presented to the Queen. He clearly felt that this was a ceremony between one ruler and another, and the dignity with which he went through the introduction was wonderful to behold. One would have thought to watch him that most of his life was spent in introduction to kings and queens, and that he was really a little bored with the effort required to go through with them.

For Cody, Queen Victoria’s request for a private command performance of the Wild West Show was the high point of his first English tour. Cody’s observation that Red Shirt appeared both relaxed and dignified when meeting the Queen of England serves as a reminder that, as one of the principal chiefs of the Oglala Lakota, Red Shirt had already experienced interactions and negotiations between “one ruler and another” when far more had been at stake.

Red Shirt was regarded by American government officials as a “progressive”. And although he had been educated in traditional Lakota values, Red Shirt informed the Central News reporter that he now believed that “our children will learn the white man’s civilization and learn to live like him. It is our only outlook in the future.” It is hard to ascertain to what degree Red Shirt’s declaration was politically nuanced, but it is undeniable that just 8 years before Buffalo Bill’s contingent of Lakota set sail for England, the tribe had been persuaded to provide the very first contingent of students for the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania.

(J.N. Choate, Cumberland County Historical Society)

The school’s founder and first principal explained that “the children would be hostages for the good behaviour of their people” (Pratt 220). Carlisle Indian School had been founded in 1879 with a mission to eradicate Native cultures and re-educate Native youth in white ways, in preparation for American citizenship. Although there is no evidence that Red Shirt’s children (Annie, William, and Joseph Red Shirt) ever attended the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, several of the Wild Westers who travelled with the first Buffalo Bill tour of England were parents of children enrolled in this first group of Carlisle students. And some of them –most notably American Horse’s and Blue Horse’s children– would go on to become second generation Wild Westers with Buffalo Bill. We will track their stories in future posts.

The Buffalo Bill Wild West Show presented an exultant narrative of the triumph of “civilization” over “savagery” and English audiences, as we have seen, were not invited to reflect on the complex histories of Native American peoples. They also probably never considered the powerful effects that time spent in England had on the “Indians” themselves. Red Shirt suggested that, “Our people will wonder at these things when we return to the Reservation and tell them what we have seen.” One aspiration of this project is that members of the Lakota community may have Wild West stories they wish to share.

SOURCES:

Pratt, Richard Henry, Battlefield and Classroom: four decades with the America Indian, 1867-1904 (1964)

Carlisle Indian Digital Resource Center – http://carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/

The William F. Cody Archive – http://codyarchive.org/images/

“The Sioux Chief Red Shirt Interviewed,” – http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/3472620

I am the great grandson of Red Shirt. I found it very interesting and informative about this history.

This is a very interesting page thank you for your research. I look forward to reading the experiences from 1903-04 because I think this is when my great grandparents were part of the show